It’s often said that small arms technology has plateaued; that development of better kinds of weapons is essentially unfeasible for the moment, and that non-optic related small arms technology had pretty much reached its peak by 1965. It would be very difficult to cover the state of the art and how to improve it in-depth, so I won’t. Instead I want to take only a moment of our readers time to explore an often-missed element of firearms technology that is the key piece in understanding the technology “plateau” and how to end it.

That element is volume.

The single most important characteristic of any military arm – that is, anything that can be wielded in some way by a man or men – is the volume with which it can be produced. All other characteristics, while also very important, are secondary.

A rifle, musket, pike, or any other arm must be producible in large volumes – today, on the order of several hundred thousand rifles per year for rifles and billions of rounds per year for ammunition, for the United States. Any concept, regardless of its advantages, that falls significantly short of the volume its host country requires must be rejected.

When met with the fact that caseless ammunition – or any other advanced small arms concept – has been around for decades without producing a single operational infantry weapon, it’s very tempting to claim that it will never be feasible to produce caseless weapons for military use. Consider, though, that Henry VIII owned breech-loading rifles (indeed, you can still go see them at the Tower of London); why, then, didn’t these get subsequently adopted as standard issue until the late 19th Century? Even if some institutional blindness prevented the British themselves from seeing the value of the breech-loader, surely another nation – seeking a leg up on the competition – would try to make it work, if possible.

Breechloading weapons had serious technical issues starting out, which were exacerbated when the rifles were eventually mass produced, to the point that early breech-loaders were barely serviceable weapons. Eventually, though, their problems were solved, and not only were later breech-loading weapons mass-producible, but they worked a lot better than their muzzle-loading counterparts, too.

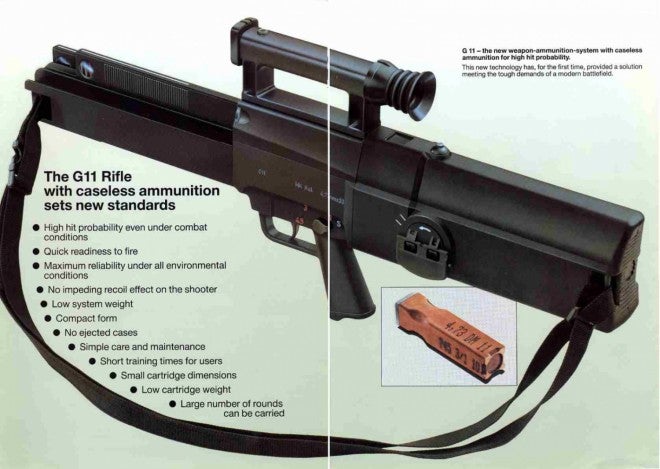

I can’t say whether the caseless ammunition concept in particular will ever come to fruition, but I think I can say how it might, if it does. The biggest problem with the concept is making the propellant blocks correctly every time. Doing so is difficult, especially when producing any sort of volume of ammunition. The caseless concept, therefore, will finally reach the end of the tunnel when it is possible to produce a billion blocks of near-perfect RDX propellant per annum.

There’s your plateau. It’s not the engineering of the small arms or their ammunition that’s holding us back. It’s the production engineering.

So who will break the stalemate? Where’s our next Dreyse? Our next Garand?

Your Privacy Choices

Your Privacy Choices