Welcome back to Wheelgun Wednesday, our weekly article series where we cover everything related to revolvers. Today’s topic is the technical challenge of effective sound suppression of revolvers. While we all know that the cylinder gap prevents proper suppression, we will look at different workarounds, developed by designers across the world. There’s no universally accepted categorization of solutions to this problem, but for the sake of simplicity we’ll arbitrarily divide the approaches into three groups:

- Sealed revolvers

- Gap sealing cartridges

- Silent cartridges

This week we’ll introduce the challenge and then focus on the first group, leaving the second and third to other Wednesdays.

Wheelgun Wednesday @ TFB:

- Wheelgun Wednesday: Smith & Wesson Texas Rangers Bicentennial Revolver

- Wheelgun Wednesday: Penn Arms GL65-40 Launcher

- Wheelgun Wednesday: Double Revolver from San Marino

- Wheelgun Wednesday: Super Redhawk 22 Hornet! Who Approved This?!?

- Wheelgun Wednesday: Taurus Judge Home Defender or Fake Pretender?

Wheelgun Wednesday: Silencing the Gap – Part 1

The Cylinder Gap

The main reason why revolvers are poor suppressor hosts is the fact that a small amount of hot, high-pressure gas, leaks from the gap between the cylinder and the barrel when the bullet leaves one for the other. This loss of gas primarily affects the bullet’s muzzle velocity, and it poses a potential danger to digits inadvertently placed close to the gap. On top of this, more relevant to our topic, the escaping, expanding, gas has its own sound signature.

Wheelgun Wednesday: Silencing the Gap – Part 1 – Gas escaping the cylinder gap of a .500 S&W Magnum revolver (Credit: Nicholas C.)

How much gas are we losing with the gap? It would be hard to measure its volume, but an interesting test by Ballistics By The Inch shows us the effect on velocity, across different loads and barrel lengths, with a very narrow gap of 0.001″ and one of 0.006″ compared to no gap at all. A rough evaluation of the results, in barrel lengths from 2″ to 6″, tells us that the muzzle velocity decreases from a minimum of 2.6% to a max of 12.0% (large gap) and from 2.2% to 7.3% (narrow gap).

Another interesting point shown by the test is that a longer barrel has more velocity loss (in percentage) than a shorter one, as the longer barrel time allows for more gas leaking out of the path of least resistance, i.e. the gap. We can expect that a suppressor at the muzzle, acting as a barrel extension and additionally generating back pressure, would increase this effect.

While the vast majority of revolvers live happily with the drawbacks of the unsealed gap, a few designers offered solutions meant to prevent the leak.

Natively Sealed Revolvers

As Rusty showed us in this fascinating edition of Wheelgun Wednesday, the concept of sealed revolvers is not a modern affair. We can see early examples well before the era of metallic cartridges, at the time suppression definitely wasn’t a concern, the risk of chain-firing and possibly velocity loss were the problems being faced.

Wheelgun Wednesday: Silencing the Gap – Part 1 – Parker Field Gas Seal Revolver (Credit: Gunrestorationco.uk)

The most famous sealed revolver is certainly the Russian M1895 Nagant, an interesting design that obtains the gas seal by combining both a mechanical feature and a unique cartridge. Upon firing the cylinder is pushed forward, allowing the neck of the case, which extends past the bullet, to partially enter the barrel. The bullet, moving forward and pushed by the expanding gas, deforms the neck of the case, creating a tight seal between the cylinder and barrel.

As we’ve seen in Adam‘s article, the 130-year-old design is still the firearm of choice for those who look into efficiently suppressing a revolver.

Wheelgun Wednesday: Silencing the Gap – Part 1 – Threaded M1895 Nagant with its peculiar 7.62x38mmR rounds (Credit: Adam Scepaniak)

The only recent design showing potential for limited gas leakage, thanks to an enclosed cylinder, rather than a sealing feature, is the bullpup revolver Zenk. However, while intriguing, this design so far is not available on the market.

The reason for the Zenk’s enclosed cylinder is more similar to what we’re seeing in the most modern attempts to seal the cylinder gap. Placing the aforementioned gap (=gas blade) closer to the flesh of the shooter requires a targeted design effort in order to eliminate the risk of injuries. The most interesting revolving shotguns, unfortunately, none with commercial success, all adopt a form of seal between their massive cylinder and the barrel. These are the Pancor Jackhammer, the Pentagun, and more recently the Crye Precision Six12. The latter was also meant to be suppressed, making full use of the sealed solution.

Wheelgun Wednesday: Silencing the Gap – Part 1 – Suppressed Crye Six12 (Credit: Crye Precision)

With the lack of commercially available sealed revolvers, those willing to suppress one, while using normal ammunition, can look at permanent or temporary modifications.

Modified Revolvers

The PSDR is most likely the only known fully suppressed revolver manufactured starting from a commercial model. Born as a S&W 625, the firearm has a modified cylinder, an integrally suppressed barrel and a clamshell fully enclosing the cylinder in order to contain, divert, and slow down any gas escaping from the gap.

Wheelgun Wednesday: Silencing the Gap – Part 1 – PSDR III in .45 ACP (Credit: Peters-Stahl)

It is fairly obvious that models like the PSDR are highly specialized weapons, not something that we can expect to see on the commercial market. However, there has been an attempt to offer a relatively accessible way of sealing a revolver.

Aftermarket Solutions

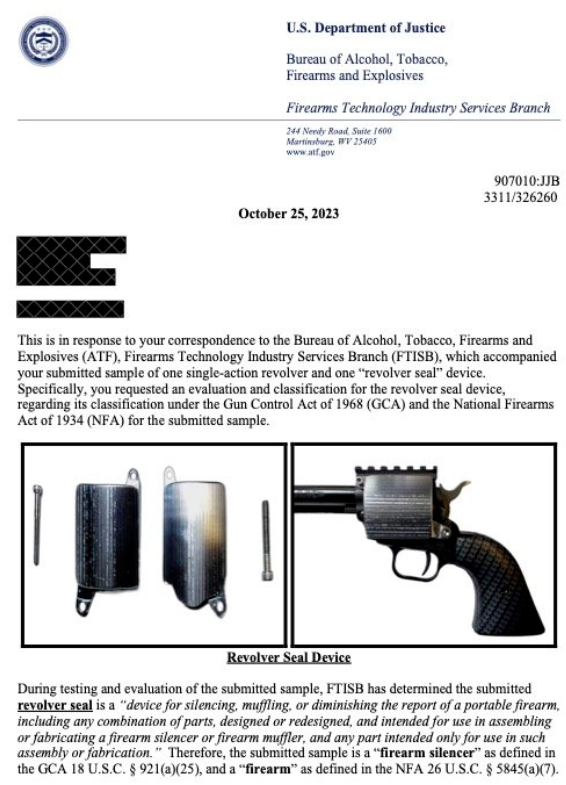

The Revolver Seal is a simple system that employs two aluminum shells to be bolted at each side of the cylinder. Initially available only for a couple of rimfire revolver models, it does require a permanent modification (holes drilled through the frame) and it is surely going to make reloading a chore, but it appears conceptually sound.

Wheelgun Wednesday: Silencing the Gap – Part 1 – Revolver Seal on a Ruger SP101 .22 LR (Credit: Revolver Seal)

However, at the moment, this accessory is not available on the market, as the ATF deemed it a “firearm silencer” completely disregarding the fact that the actual suppression would still require an actual, regulated, silencer at the muzzle. From a technical perspective, the seal is a silencer as much as a threaded barrel alone is one. Hopefully, the company will be able to successfully challenge this classification to further develop the product.

Wheelgun Wednesday: Silencing the Gap – Part 1 – Revolver Seal ATF deliberation (Credit: Revolver Seal)

Patents out there

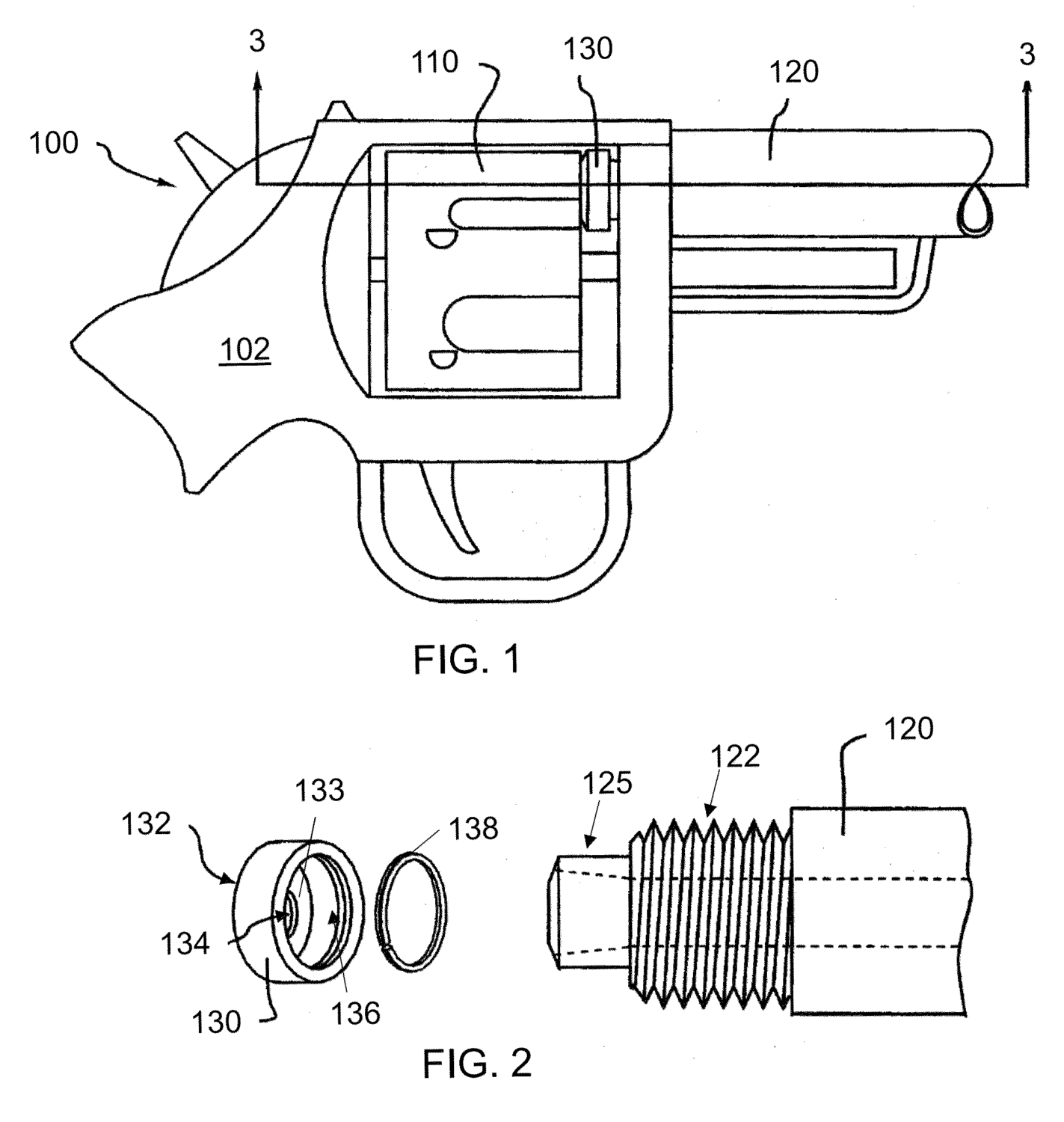

While the actual market interest for a sealed revolver seems quite limited to actually push manufacturers to modify tried and tested designs, there are a few active and expired patents covering potential solutions. One that appears promising is the sliding sleeve by Daniel J. Kunau, a relatively minor modification to existing geometries that seems to utilize the air being pushed by the moving projectile, and possibly inertia, to push a sealing sleeve from the barrel against the cylinder face.

Wheelgun Wednesday: Silencing the Gap – Part 1 – An embodiment of the gas seal from Patent US 9,423,196 B2 (United States Patent and Trademark Office)

We’re not aware of this reaching any prototype status. We can guess that the inventor may have proposed it to several manufacturers and none so far decided to implement it commercially.

A quote from the patent seems to hold quite true:

Various alternatives have been suggested in the past to solve this problem, going back at least to a patent by John E. Tyler granted on Sept. 8, 1885 as U.S. Pat. 325,878, but none have been practical or effective enough to be included in high-volume revolvers sold today.

Conclusion

As we’ve seen, there is potential out there for quite a few fully sealed revolvers, but nothing really available aside from antique guns. And the market doesn’t seem to be large enough to push large manufacturers to invest in this direction.

What do you think? Would you try an aftermarket accessory that allows you to suppress your favorite revolver? Or would you rather have a revolver coming from the factory with a simple sealing device? Do you know of other mechanical gap-sealing solutions? As usual, let us know in the comments.

Your Privacy Choices

Your Privacy Choices