In January of 2001, the US Army introduced a new slogan to replace the classic “Be All You Can Be” which young men had recruited under for over two decades. The branch’s new slogan was “An Army of One”, signalling a brand new take on a force that wanted desperately to reinvent itself. Those behind the slogan sought to re-humanize the Army, atomize it, bring it down to its individual components, i.e., the people who filled its ranks. It would be, they hoped, the slogan of a new Army that through the strength of its individuals helped make the world a better place. Over the next 5 years, however, it became the slogan under which men and women all over the world would sign up to fight in Afghanistan and Iraq as part of what became known as the Global War on Terror.

The slogan communicated the complete antithesis of everything an army should be. Armies are not about individuals in isolation, but about teams of people working together towards a single aim. They are not about making people feel special, but about winning wars. “An Army of One” branded the Army as a force, not of disciplined units working in concert, but of heroic individuals fighting alone. As a reflection of what the Army should be, “An Army of One” was a complete failure. It was quietly retired after just five years in 2006, replaced with the current “Army Strong”.

Since then, it seems that the mindset communicated by “An Army of One” – far from dying quietly – has instead proliferated into the community of officers, experts, and corporate partners who concern themselves with the future shape of the Army, and especially its materiel. Boardroom presentations communicate the supposed need for “the warfighter” to “overmatch” his enemy, reducing the sophisticated heterogeneous organization of the Army to just a single individual in the same manner as did that ill-conceived slogan. “The warfighter” is, of course, no one in particular, but it is supposed to represent anyone with a combat MOS. “Overmatch” is so loosely defined that it means almost nothing, but it is supposed to tell us what “the warfighter” needs to do their job.

The result is a concept that has no meaning beyond good feelings, but that is useful to those with an agenda. Since “the warfighter” can be anyone, and “overmatch” can be measured against anything convenient, it’s easy to communicate the sense of a crisis where there is none. If a lobbyist tells planners that “the warfighter” is “overmatched” by Russian-made 7.62mm machine guns, this creates the sense of a capability “gap” – even though the US Army has been procuring comparable machine guns for over half a century. The utility of this vague language to industry solicitors and their partners is obvious.

Saying this does not necessarily imply that all those who use this language do not have good intentions; we must also consider the effect the language has on the way we think and how we interpret reality. If all 26 US Army combat MOSes are distilled down to just “the warfighter” – represented of course by the grunt and his rifle – then any sense of supporting arms and their effect on the equation is lost. This, by extension, diminishes what should be a picture of combined arms into one where all combat responsibilities are borne on the backs of the rifleman alone. By this thinking, if the enemy has medium machine guns, then every rifleman must be equipped to counter them. This is the flawed fundamental logic of “overmatch”, and it does not reflect the way the Army or any other branch of the United States military actually fights and wins wars.

U.S. Army Staff Sgt. James C. Allen takes cover from small arms fire in Qara Khel, Paktika province, Afghanistan, July 30, 2011. This is what we picture when we think of “the warfighter”: a single, solitary soldier engaged in a fight for his life, armed only with a rifle. Not pictured, however, are the other members of his unit and their supporting arms. Photo by: Spc. Jacob Kohrs, US Army. Public domain.

The bent perspective behind “overmatch” has been years in the making. From 2001 on, soldiers embroiled in fighting in Afghanistan and Iraq came face-to-face with the limitations of their weapons. Rifles did not put down insurgent enemies in one hit, as expected, but sometimes required multiple rounds to end a threat. Infantrymen with both rifles and carbines were unable to affect targets out to the distances and to the degree that they had been led to expect by their technical manuals. On the corporate side, Colt’s stranglehold on M4 Carbine contracts prior to 2009 gave other rifle manufacturers great incentive to persuade the Army to hold competitions for its replacement. As long as Colt’s was the sole source for the M4, no other company could get a carbine contract. Further, if another company managed to get a sole-source contract for their own design, they would have exclusive rights to manufacture carbines for the foreseeable future. These and other factors together resulted in an extended and decentralized campaign to discredit the M4 Carbine and the 5.56mm round, a campaign which continues to this day.

In the past several years, however, this campaign has taken a turn. Prior complaints regarding close range lethality have shifted to a supposed need for infantry rifles and carbines to engage and defeat targets out to 800 meters and beyond. Enemy small arms like the SVD designated marksman’s rifle have been inflated in importance and effectiveness, in an effort to help sell the idea of a capability gap between NATO weapons and their Russian and Chinese counterparts. The Russian PKM machine gun in particular has been portrayed not as an equivalent to the US M60 and M240, but as a far superior and far longer-ranged weapon. Even the Chinese 5.8x42mm assault rifle caliber is routinely portrayed as overmatching the US 5.56mm, despite it having, at best, only a modest ballistic advantage.

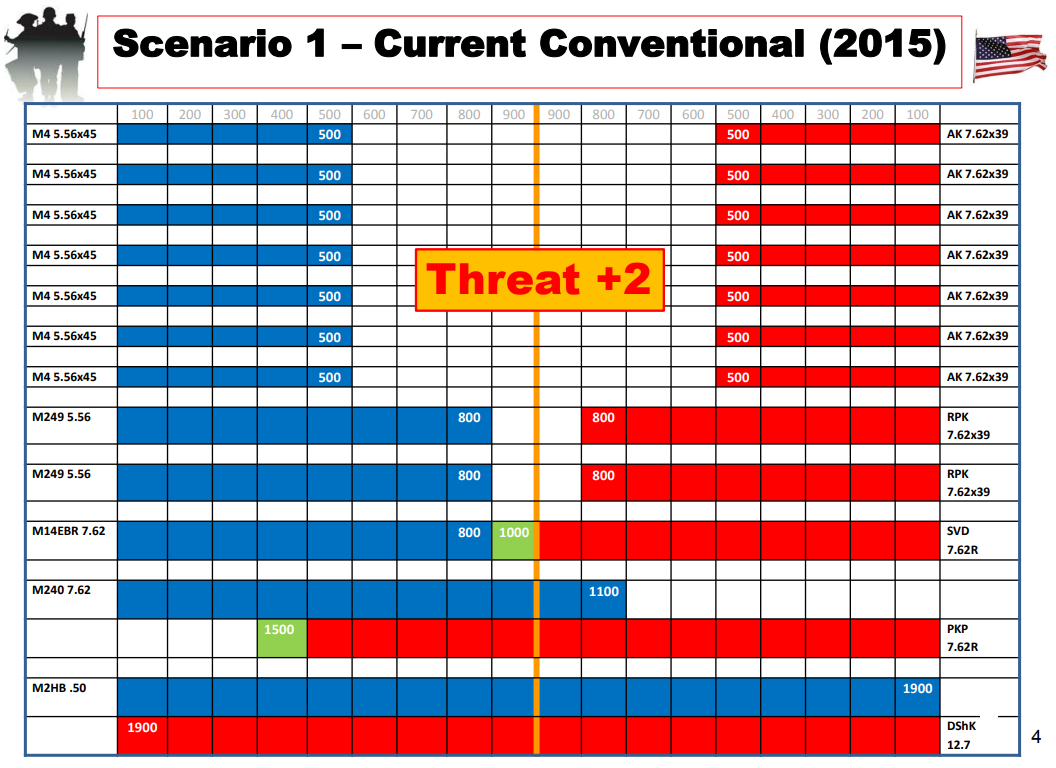

A chart identifying areas of “overmatch” in the infantry fight. Exactly how the SVD and PKP, both of which fire a round virtually identical to the US 7.62x51mm ballistically, out-distance their NATO counterparts by hundreds of meters is unexplained. From the late Jim Schatz’s 2015 NDIA presentation Where to Now?

This shift in emphasis can be attributed to four primary factors: First, a number of engagements in Afghanistan from 2007 onward saw US troops fall under ambush from medium machine guns (usually PKMs) emplaced at extended ranges (800m or more). Second, beginning in 2010, the US Army began fielding a much more consistently effective and higher performance 5.56mm round, the M855A1, which has helped quiet complaints about the lethality of 5.56mm weapons. Third, criticism of the M4 Carbine and the AR-15 platform in general waned with the end of Colt’s exclusive contract for the weapon in 2009, giving Colt’s primary competitors the opportunity to cash in on the program. Fourth, massive increases in civilian ownership of higher quality (“mil-spec”) AR-15s beginning in 2010 considerably improved the reputation of that weapon and its direct impingement gas system in the eye of the concerned public.

With any major faults in the M4 platform no longer obvious in the public perception, and with the lethality of the 5.56mm round substantially augmented by new ammunition, critics of this weapon and its caliber needed a new anvil to strike. Growing concerns about US rifle and carbine lethality at extended ranges (>600m) provided the new change in tack, and the term “overmatch” was popularized as a result. Perhaps contributing to this popularity within the industry is the fact that, unlike with the AR-15, no industry standard exists for AR-type rifles with cartridge overall lengths (OAL) longer than 2.25 inches. This creates substantial incentive in the gunmaking industry to convince the Army to adopt a new weapon with a longer OAL. Any company whose proprietary design won a resulting competition would receive substantial contracts for at least the next decade, and probably beyond, netting them hundreds of millions of dollars or more.

Different proprietary specifications for the same round: The HK G28E CSASS (top) and Colt 901 CSASS (bottom). Any contract for a standard rifle firing a round with a longer overall length than the current 5.56mm would necessarily have to be sole-source, making the US Army dependent on a single manufacturer for all their future individual weapons. This would repeat the mistake made when the US Army allowed Colt to retain exclusive rights to the M4 Carbine.

Defining the word “overmatch” itself presents an issue, as it is used in a way that is essentially equivalent to the more familiar “out range”. Like “out range”, it is an ambiguous term that does not precisely correlate to any specific performance aspects or benchmarks. Although different rounds have different characteristics – one round may be superior in performance to a second round in one respect, while being inferior in another – “overmatch” does not identify in which of those characteristics lies the supposed gap in performance. Therefore, any attempt to optimize ammunition according to this principle is undercut from the beginning.

Whether this is deliberate or not is unclear; what is clear is that “overmatch” expresses the goal of massively exceeding the performance of enemy weapons. Doctrine, requirements, and optimization criteria have largely been abandoned by overmatch proponents in favor of an organic approach based on feeling and perception. If proponents of this principle are presented with a hypothetical round that meets notional criteria for overmatch but that appears too small or weak, they will reject it. In contrast to the vagueness of the word itself, proponents of overmatch have very specific ideas regarding what next generation ammunition must – quite literally – look like. In short, “overmatch” acts essentially as an identifier for those who feel the modern SCHV paradigm – including the US 5.56mm, Russian 5.45mm, and Chinese 5.8mm – is too small and weak for the modern soldier.

If overmatch is to be the rule by which next generation small arms systems are developed, then it raises the question of what, exactly, are these weapons intended to overmatch? If a rifle is intended to overmatch just the enemy’s own rifles, then it is already done – the M4 is already the equal or better of the AK-47, AK-74, and QBZ-95 rifles in use by our current and potential adversaries. If the rifle is intended to overmatch the enemy’s machine guns, then one might ask where our own machine guns and other weapons are intended to be if not countering the enemy’s, and why it must fall to our riflemen to do these jobs instead? Moreover, if the rifleman is expected to counter the 7.62mm tripod-mounted machine gun, why not the .50 caliber machine gun as well? Or the 14.5mm machine gun? Or the 60mm mortar, or any of the myriad of other light support weapons that dot the battlefield? This is to ask: Where does overmatch end?

This is the first of three articles on the subject of overmatch. In the following two installments, we will examine the deleterious effect that the overmatch principle has on requirements and optimization, as well as why abandoning lightweight small caliber ammunition in favor of heavier, higher-performing rounds “locks out” the infantry from using the force multipliers of the future.

Your Privacy Choices

Your Privacy Choices