Military procurement is a very precise business, in which the costs, drawbacks, and benefits of different ideas and proposals are weighed in the balance, and those that don’t make the grade are relegated to research status or cancelled outright. It’s also a very messy business, rife with opportunities for graft and corruption, and one that by its nature is prone to wasting money. It’s certainly true that our current system of military procurement badly needs reform to prevent waste of taxpayer dollars and to ensure the best equipment is purchased at the right price.

However, we don’t get from here to there through the kind of process outlined in an article hosted at National Review, written by retired Major General Robert Scales, US Army. I’ve tussled with Scales’ writing twice before, both times concerning his criticisms of the M4 Carbine, but this time Scales presents what he believes are cheap, off the shelf technologies that could easily be bought by the government to improve the infantryman’s effectiveness in combat. Unfortunately, despite his apparently good intentions, Scales does not seem to have a very good grasp of the material, and the ideas he proposes range from wasteful to half-baked, including several combinations of the two thereof. More fundamentally, Scales falls into the trap of wanting to take the easy way out, following the allure of commercial off-the-shelf programs that in every case he outlines promise much to the uninformed, but in practice would not meet the needs of the US combat infantryman.

Since in the two aforementioned articles I have already addressed just about every criticism Scales has regarding the AR-15 family of weapons (including the M4 and M16), I recommend readers click through and read those if they are interested in my refutation of Scales arguments. The first post is a little regrettably flippant on my part, but the second follows through with more detail. I also recommend reading a handful of other articles I have written regarding reliability and the AR-15 family of weapons, including How Well Does Direct Impingement Handle Heat? and Jim Sullivan On The M16 In Vietnam (And Commentary By Daniel Watters), the latter of which handles the subject of why the M16 failed in Vietnam.

However, Scales makes a couple of strange assertions about the M4 that are worth addressing here, separately. One is that “Russia’s newest rifle outranges ours by 40 percent”, which is a very nebulous claim with absolutely no evidence behind it. It’s not clear what rifle Scales is talking about, nor the effective range values he believes are applicable to either it or the US Army’s M4 Carbine. Is Scales talking about the AK-12, and if so does he believe the AK-12 is somehow a 700 meter gun to the M4’s 500 meters, or what? Maybe he means Kalashnikov Concern’s new SVK designated marksman rifle, which is neither designed as a standard infantry weapon nor has even been bought by the Russian military as of the date of publishing. Statements like these are impossible to disprove because it’s impossible to know what Scales means without further clarification. The reader is simply expected to take Scales’ word for it.

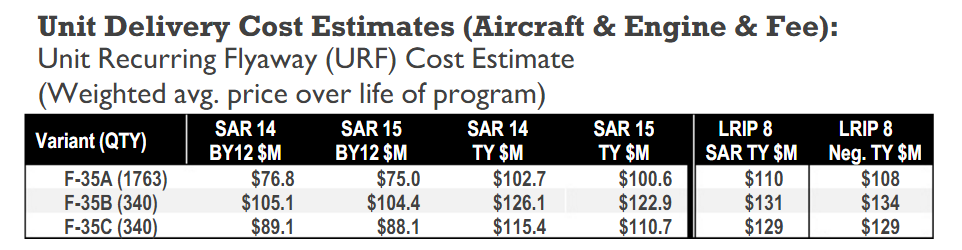

The other assertion Scales makes is that “[w]e could equip every close-combat soldier, Marine, and special operator in our military for the cost of a single F-35 fighter jet”, which, like the previous, is almost hopelessly vague. I assume Scales means that we could replace all the rifles in inventory for this much, but with what? Again, we are left in the dark. With our reader’s pardon, though, I’d like to dig a little deeper into this claim, since I hear the unit cost for F-35s referenced so much in discussions about procuring new small arms. Let’s work the problem frontways and backwards, starting with the unit cost of an F-35 itself. How much a single F-35 costs depends on the variant (there are three), but let’s take the cheapest and most plentiful one: The US Air Force’s F-35A CTOL version. The cost of a single F-35A is still difficult to pin down exactly, but it’s easy enough to get as close as we need for our purposes. There are a lot of different sources on this, including a CNBC article slamming the fighter, and F35.com which is presumably biased in the other direction, but the best source seems to be a Breaking Defense article which references a 2015 Selective Acquisition Report on the F-35. That breaks down the cost like so:

So each F-35 is expected to cost on average about a hundred million bucks, while the low rate initial production units are costing about a hundred and ten million bucks per, in then-year dollars. Let’s go with the hundred million dollar ($100 million) for a single F-35A.

Scales is also imprecise on who exactly we are equipping in his plan, as “every close-combat soldier, Marine, and special operator in our military” includes quite a lot. Since this line is pretty ambiguous (do infantry reservists and National Guardsmen count, or only people in-theater? What about combat units that are out of the rotation, or troops on active duty in potential war zones like Korea?), I’ll replace it with a number I’ve heard bandied about a lot: 140,000 US Army active duty deployed combat troops. If we throw the Marines and miscellaneous others in there, we can probably call it a round 200,000 troops that would need to be re-equipped.

From there, the math is simple: 100,000,000 divided by 200,000 gives us our budget per soldier, airman, sailor, or Marine, which works out to $500 a pop for the cancellation of a single F-35 fighter jet. That is not a lot of money to procure new rifles if Scales demands for a new caliber and a new operating system are to be met, along with the normal standards expected of military rifles. It is certainly not enough money to also purchase new ammunition, accessories, optics, and the other things that Scales thinks would make great “Christmas gifts” to go along with the new weapons.

Going the other direction, I recently wrote about the costs of procuring new rifles, using for my accounting a rifle concept that seems to fall right in line with Scales’ recommendations. Sadly for the Major General, the conclusions I came to certainly don’t line up with Scales’ assessment that US troops could be re-equipped for the cost of a single F-35:

Therefore, a new rifle of this type would probably have a cost breakdown like so:

- Base rifle, grip, bipod, rails, light – $3,000 – $5,000

- Long Range Rifle Optic – $2,000 – $3,000

- PEQ-15 – $600

Total cost for our new long-range infantry rifles would therefore be somewhere in the ballpark of $5,000-$9,000 per unit, not including spares and support. This, however, is an estimate based on contracts with relatively low procurement numbers, so to adjust for economies of scale, we need to look to a larger contract. The French this year awarded Heckler and Koch a contract for over 100,000 of their HK416F rifles, at about $4,200 per unit, including spares and support. If we compare that to the USMC M27 contract, we get an imperfect but serviceable adjustment of 0.70 to account for the economy of scale, resulting in an estimated cost per unit for our rifles of $3,500-$6,300. We’ll just round that to $3,500-$6,000.

So a single F-35 buys you a little over 30,000 guns if you leave off the PEQ-15 (presumably still in inventory after you scrapped all the M4s), given the most optimistic cost estimate for a new rifle system. To buy 200,000 rifles, you need to cancel six F-35s. Keep in mind this is accounting for procurement of rifle systems only, not development of those rifles, and not development and procurement of ammunition, magazines, accessories, etc., either. As we examined in a previous article regarding a hypothetical adoption of the 6.5 Grendel, development of only a few of these items would probably cost hundreds of millions of dollars alone, and procurement of an entire fleet would run well over a billion dollars, not including training and other essential items.

Still, even assuming a few billion dollars worth of procurement costs, we’re only cancelling a small portion of the F-35 fleet, right (the US Air Force alone plans to buy 1,763 F-35s)? Well, there are flaws to this logic. First, if the money is to be freed up by cancelling F-35s, when are these F-35s being cancelled and how are the gaps being filled? It’s my assumption the Scales would like this rifle procurement to happen effectively now, so what does three billion dollars worth of rifles, optics, magazines, ammunition, spares, training, packaging, etc look like in terms of delay in F-35 procurement? The Air Force’s goal for procurement of F-35s for 2016 and 2017 is 48 birds per year, meaning an immediate initial three billion dollar purchase of new infantry weapons would axe almost two thirds of the aircraft slated for procurement in 2017. With current airframes wearing out and desperately in need of replacement by the new aircraft, this raises the question: Is it really worth it?

Stepping back, we have to recognize that we are indulging in a minor fantasy; it may not be that F-35s actually get cancelled to procure new rifles, but that still has us asking where we will find the money to procure these weapons? If new rifles are to be purchased any time soon, how many other programs are we willing to cancel in service of this dream of new infantry weapons?

I think it’s very important to listen to people who – like Scales – went through one of the greatest procurement disasters in modern US military history, that being the M16’s combat debut in Vietnam. Scales may (or may not) have the right motivations, but I think from this disaster he draws some incorrect conclusions. The Major General wants the easy way out, a commercial off the shelf (COTS) procurement program of new and better equipment that would give the US soldier an edge. Yet it was precisely that approach which resulted in the M16’s failure in Southeast Asia that Scales so laments. The rifle was procured off the shelf from Colt with no questions asked after the disaster that had been the government-produced M14 (itself a boondoggle program that had the Scaleses of their day crying for heads to roll – and roll they did). The M16 was introduced prematurely and men died as a consequence. Had those rifles been developed, tested, and procured properly, more of Scales’ men might still be alive today. I don’t say this lightly – the business of military procurement has a grave end: The nation’s fighting men rely on the equipment they are given, and live and die by how that equipment was developed, tested, and procured.

Let’s not fall prey to fraudulent accounting and the allure of easy COTS solutions. As frustrating as our military procurement system often is, it’s also necessary to save the lives of the men who count on it.

Your Privacy Choices

Your Privacy Choices