We are all familiar with the standard conspiracy theories: NASA faked the Moon landing on a Hollywood soundstage, President Kennedy was shot by another gunman who was working for the CIA/the mob, all world leaders are actually reptilian aliens from Alpha Centauri, and the others. If you’re a gun person, though, there’s one other conspiracy theory you probably know: The official history that Mikhail Kalashnikov designed the AK-47 assault rifle was a Soviet hoax, propagated by state agents as a propaganda narrative to promote the idea of Soviet exceptionalism.

And I’m here to tell you that this conspiracy theory is complete bunk.

A disclaimer is in order. I am not a fan of communism, nor of the Soviet Union. My thesis here is based on the evidence, not a political agenda or narrative. I have looked at the facts as honestly as I am able, and come to a conclusion: The idea that Mikhail Kalashnikov was not responsible – in at least the usual fashion that designers are responsible for their work – for the design of the AK-47 rifle is not at all supported by fact.

Now, let’s look at some of the common arguments that crop up under the umbrella of this theory and examine why they are evidently false:

1. The StG-44 was the first assault rifle, so the Soviets must have copied the concept from the Germans.

A staple argument of this conspiracy theory is that the AK-47 is a similar weapon to the German StG-44, which preceded it, and therefore isn’t a Soviet product or idea. It is certainly true that the Nazi sturmgewehrs were the first truly successful assault rifle designs in the world, but the relationship between the StG-44 and AK-47 is often presented in an overly simplistic way that ignores much of the surrounding context. It follows then that, to counter this argument, we need to understand some of the context surrounding these weapons.

The idea of an assault rifle was born in several Entente countries nearly simultaneously during and immediately after World War I, as a way to give assaulting infantry the ability to counter static machine guns. There is a strong argument to be made that the CSRG Mle. 1915 Chauchat, M1918 BAR, and “Assault Phase Rifle” designed by Colonel Lewis (which was the first weapon to actually be called an “assault rifle”) all represent the earliest incarnations of the concept, even though they fire full-power ammunition. However, intermediate-caliber designs existed at the time, as well, such as the American Burton Machine Rifle, French Ribeyrolles 1918 machine carbine, and Russian Fedorov Avtomat. After the war, the idea of an “assault rifle” persisted in engineering circles, and many different intermediate rounds were developed (and one – the 7.35x50mm – even adopted in Italy) along with semiautomatic and select-fire weapons to fire them.

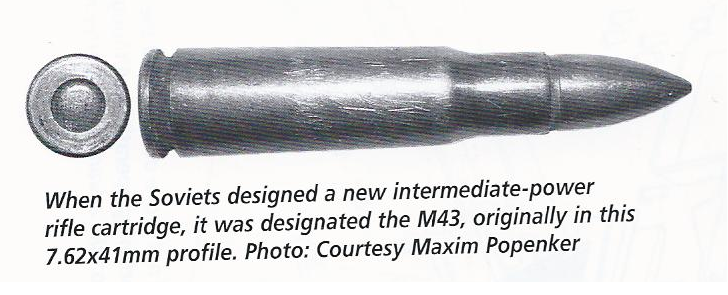

Therefore, the appearance of the Nazi sturmgewehrs on the battlefield in World War II was not completely unprecedented. Germany had obviously taken the concept of an assault rifle further than anyone else before, but Soviet engineers would likely have been at least aware that the concept existed previously – not the least because the old Fedorov Avtomats had actually seen action in the Winter War of 1940 and in World War II! Indeed, Vladimir Fedorov would continue working as a small arms engineer well after World War I, and he was directly involved in the mid-1940s in the effort to adopt the 7.62mm short M43 caliber (then 7.62x41mm, later 7.62x39mm).

The original 7.62x41mm caliber developed in 1943 was a precursor to the now-ubiquitous 7.62x39mm. This round was a direct response to the German 7.92x33mm Kurz, but it preceded the invention of the AK-47 by four years.

This isn’t to say that the sturmgewehr didn’t make an impression on the Soviets: It’s difficult to imagine an enemy small arm that had as much impact on Soviet small arms design as the StG-44, but put into context the weapon represents more the proving out of a pre-existing idea than the introduction of something completely new.

We should also consider the Soviets’ combat experience with their own weapons. The Red Army had successfully fielded millions of PPSh-41 and PPS-43 submachine guns, sometimes to entire battalions of submachine gun-armed soldiers. This experience demonstrated that even the limitations of a submachine gun were not such a disadvantage that these weapons could not be used as universal weapons at least in some cases. From that unique vantage point, the acceptance of the assault rifle idea seems entirely natural, even without the existence of the German sturmgewehrs.

2. The Russians captured German engineers after the war, so it must have been Germans who invented the AK-47, not Russian engineers.

There’s a certain logic to this argument, by way of analogy to the American rocket program in the 1940s, ’50s, and ’60s. As part of Operation Paperclip in 1945, the United States captured hundreds of German scientists and engineers and put them to work wherever they could, most famously at the task of developing new rocket launch vehicles for use as military missiles. These experts became a crucial part of the later US space program, and to this day aeronautical engineer (and former member of the Nazi Party) Wernher von Braun is still the person most closely associated with the development of the Saturn family of rockets that took US astronauts to the Moon.

Wernher von Braun is recognized as one of the chief architects of the USA’s space program after World War II. Here he is posing in front of models of some NASA rockets: Atlas-Centaur, Saturn I (unmanned and crewed), Saturn IB, and Saturn V. Before the war, von Braun was a member of the Nazi Party, and worked developing missiles for the Third Reich, most famously the V-2.

This history then creates the framework for a narrative where German technical experts are captured by the Soviet Union and put to work in a similar fashion – and indeed they were. However, this fact doesn’t imply that the results of Soviet post-war rearmament efforts were the products of German engineering, and in fact the evidence suggests otherwise. One of the most obvious facts is that the Russian program to develop an assault rifle was in high gear by early 1944, well before any German small arms engineers were ever captured. In fact, ten different Russian assault rifle designs competed in trials in early 1944, including designs by Tokarev (AT-44), Shpagin (ASh-44), and Sudaev (AS-44). Sudaev’s design in particular was so successful that trial quantities were ordered and the rifle saw limited service at the end of the war.

By the time German technical expertise was being incorporated in 1945-1946, they were not forming the core of a new program, but rather joining an already mature Russian design effort to develop an advanced assault rifle. In this light, the development of an assault rifle by Russian engineers seems entirely plausible, and it cannot be assumed without extremely explicit evidence that this history was created from whole cloth for propaganda purposes.

3. The Germans developed the advanced stamping techniques for the StG-44 that made the AK-47 possible.

It’s true that Germany was one of the biggest innovators in the field of metal stamping during World War II, but the Russians were no strangers to it, either. The aforementioned PPSh-41 and PPS-43 submachine guns were both stamped weapons made in very large quantities, and it stands to reason that the Russians would know that any new weapon designed to be made in similar quantities in the event of another world war should also be made of stampings.

One detail of special note is the substantial difference in the kind of stampings used in the AK and the StG-44. The Germans during World War II had a shortage of alloying agents like chrome and molybdenum, and one of the primary requirements for the new assault rifle was that it use as little alloy steel as possible – preferably none at all. As a result, the stamped receiver pieces of the StG-44 were made of weak mild steel sheets which were bent again and again in several operations to increase their strength, a process which gives the rifle its distinctive industrial looking ridges and bumps.

The strengthening ridges are highly visible on the receivers of this MP.43-marked sturmgewehr. Contrast that with the very slab-sided look of the AK’s stamped receiver, below. Image courtesy of Alex C, used with permission.

The receiver of the AK represents a different approach to stamping. Instead of being soft iron with only a small amount of carbon, the receiver of a stamped Kalashnikov uses higher strength alloy steel (exactly what alloy is used depends on manufacturer; American AK manufacturers tend to use 4130 chromoly steel, while Izhevsk reportedly uses 30KhGSA steel for their receivers) that usually incorporates molybdenum, chromium, and silicon in the alloy. While the receiver shell of an StG-44 needs a series of complex ridges and bumps to give it strength, the receiver of an AK does not, since its strength comes from its composition more than its shape. As a result, AK receivers can be stamped in very few operations, and the rifles made more quickly.

Note how there are no strengthening ribs or ridges on the receiver of this stamped Type 1 AK. To compensate, the receiver must be made of stronger alloy steel, but fewer operations are required for its manufacture. Image source: theakforum.net

This discussion of “pig iron” and “alloy steel” might give some the impression that I am being hard on the StG-44, but that’s not my point. Actually, the fact that the StG-44 did not use any valuable alloys was very beneficial to the Nazi war machine during World War II, as Germany did not have enough of these alloying agents to use for mere rifle production. Rather, the thrust is to highlight the difference between how these two weapons were made, and to drive home that “not all stamping is created equal”. From the executive summary of the Auto/Steel Partnership’s manual on high strength steel (HSS) stamping:

HSS often requires die processes different from those used for mild steels in order to achieve a quality stamping. Recent HSS studies at the Auto/Steel Partnership have shown that, in the range of 275 – 420 MPa (40 – 60 KSI yield strength), the wrong die process was a much greater contributor to poor part quality than material property variation. This includes the effects on wall opening angle, side-wall curl, offset flange angle and panel twist.

The product designer must understand the material characteristics and the proposed die process in order to produce a workable part design. Abrupt changes in part geometry and/or uneven depth of draw make HSS parts more difficult to produce.

[Emphasis mine]

The Germans gained a lot of experience in stampings from the sturmgewehrs, but not in doing the particular kind of operations that were eventually used in the AK-47 rifle. For what Kalashnikov’s design required, the Soviets would mostly have had to pave their own way.

Another reason we have to believe the stampings used to create the AK receivers weren’t significant beneficiaries of German manufacturing technology is how long they took to perfect. Consider that the Tupolev Tu-4, a Soviet copy of the American B-29 strategic bomber, took only three years to reach production from the 1944 capture of the originals. In contrast, it took Soviet engineers over a decade from the capture of German stamping equipment and expertise in 1945 to perfect the kind of alloy stamping needed for the eventual AKM. This fact leads me to believe that Soviet engineers were doing something with the AK that took a lot of innovating on their part, and not just copying work that Germans had already done.

There is so much ground to cover here that we really must take a break. Therefore, I’ve decided to split this post into two parts, with the second coming tomorrow. Please be patient, and stay tuned!

Your Privacy Choices

Your Privacy Choices