In the second of our 101-level discussions on firearms operating mechanisms, we mentioned that firearms may have what’s called a locking mechanism, which prevents the separation of the breech and barrel during the high pressure ignition of a round of ammunition. For 101-level posts, we’ll mostly note whether locking occurs or not and nothing more, but today’s 201 post will begin to talk about locking mechanisms in detail. First, we need to understand that there are two different things meant by the term locking. The first is the more proper understanding of a fully locked breech which must be opened by some external force, but the second is often referred to as “locked” as well, even in some professional literature. This second use is more properly called half- or semi-locked, and describes locking elements that are used in retarded-blowback mechanisms.

- Locked-breech: Describing a firearm with a fully locked mechanism, where the breech and barrel are separate pieces, but solidly coupled together during ignition of the cartridge.

- Half-locked/semi-locked breech: Describing a firearm with a mechanism that forces the breechblock to act against a mechanical advantage before opening can occur.

A cartridge when it ignites produces a great deal of pressure that acts in all directions. This pressure, as it acts against the base of the bullet, pushes it out the muzzle, but it also acts against the cartridge base and side walls, as well. The side walls of the case are held firm by the barrel, but different firearms handle the pressure acting upon the case base, differently. That brings us to talking about bolt thrust, and how it works.

- Bolt thrust: The force produced by the pressure of the propellant gases as it acts upon the base of the cartridge case.

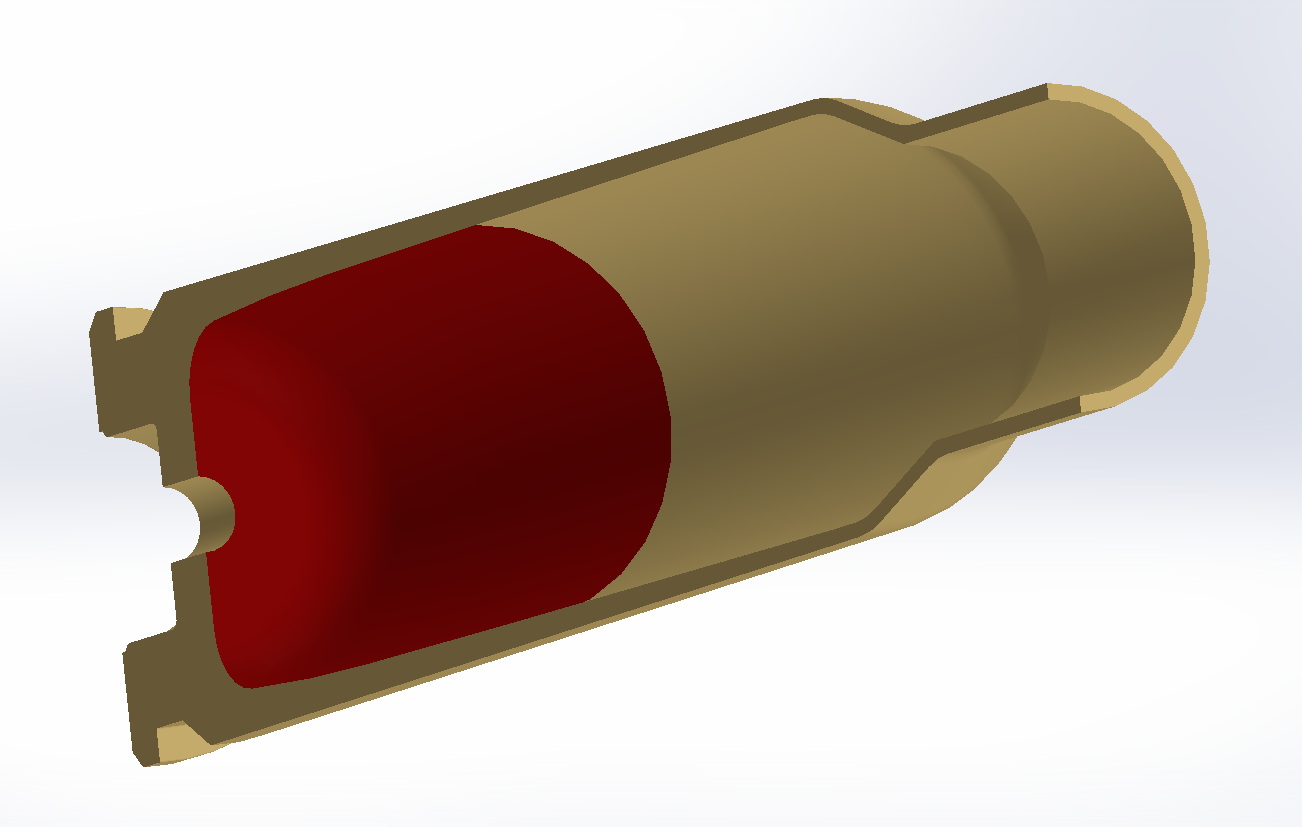

Bolt thrust is the force generated from the uprange vector of the pressure generated when a cartridge is fired. Pressure is a measurement of force over area, therefore bolt thrust is a function of a pressure measurement multiplied by the maximum internal area of the cartridge case.

A sectioned 7.62x51mm NATO cartridge case; the red highlighted area shows the area affected by the uprange vector of pressure during firing. Pressure acts in all directions, but it’s the direction opposite of the bullet’s travel that creates bolt thrust.

This means that bolt thrust is increased not only through higher pressure ammunition, but also wider ammunition, as that pressure has more area to create force on the breech face. A locking mechanism must be strong enough to contain this force until unlocking occurs. We’ll begin to explore how different designs manage these forces, and even use them to operate the mechanism, in later installments.

Your Privacy Choices

Your Privacy Choices