“Ask Doc” is a new series we are contemplating where we will answer questions from you, the readers. Topics will be answered by staff writers with significant experience in the field and tactical medicine. Submit your questions to tom.r@thefirearmblog.com (and try and keep them on topic).

Trigger warning: the following post may make you uncomfortable.

This conversation pops up every so often in threads and articles. In fact, we recently had one in the comments here on TFB on a recent article Blue Force Gear Releases Three New Trauma Kits.

I get it, I really do. There is nothing sexier in a first aid kit than advanced equipment, especially that of a giant three-and-a-half-inch, 14 gauge needle that is intended to be driven into the chest of a dying patient. But let’s red pill this and look at the reality of this oft circulated tactical trope.

Look how sexy that is. You just can’t help but feel like a super medic with one of these in your kit.

This is an opinion, honed from years of experience, and also based on research. Some people may be able to advocate for their use. I personally am well trained on the use of chest darts, have deployed them into living tissue (not a rack of ribs from the store), and absolutely think they have a place in CERTAIN CONTEXTS. Like in war zones with medics trained on long-term field care and whose training doesn’t max out once the air hisses from the needle.

Why do you need a chest dart?

That giant three-and-a-half-inch, 14 gauge needle is colloquially known as a “chest dart”, but is more appropriately a tool used to perform a needle thoracostomy to decompress overpressure from a tension pneumothorax (we will refer to this in shorthand as tPTX). First off, if you could not immediately define a tPTX per the last part of that previous sentence, that may be an indication that you have no business carrying that equipment.

Let’s deconstruct and discuss. What is a tension pneumothorax? Basically, it is air in the upper part of the chest (outside of the lungs) that cannot escape and is causing physiological effects like respiratory distress, anxiety, and if not treated, cardiac and brain injury. Another way to think of it is when the air outside the lungs blows up like a balloon inside the chest and compresses everything else, including the heart, which then can’t fill up and pump.

We need to understand a little bit about anatomy before we go further. This will be high-level, so bear with me. Think of your torso as having two parts—the lower part with all of your giblets, and the upper part with your lungs and heart. This separation is basically at the diaphragm. The heart sits in the middle and the lungs are on either side. The lungs are kind of like spongy balloons that inflate and deflate, and the lungs stick to the inside of the chest wall. This stickiness is what assists the lungs with inflating and deflating in response to the expansion and contraction of the chest wall. Basically, you have a mechanical structure (chest wall and diaphragm) that pumps the bellows.

Photo by National Cancer Institute on Unsplash

How does a tension pneumothorax form? It is really nothing more than a puncture or tear in the lung tissue (which is very thin) that allows air to escape into the chest cavity and build enough pressure to start causing physiological problems, generally associated with the collapse of the affected lung. A pneumothorax can happen spontaneously (though generally only in very tall, thin smokers). A spontaneous cause is not really all that sexy and emergency physicians routinely treat complete collapses of a single lung where the patient doesn’t have significant vital sign changes. Meaning you can have a collapsed lung with escaping air that does not develop into a tension pneumothorax.

Tension can also develop as a result of mechanical ventilation–an EMT “bagging” a patient with a Bag-Valve Mask (BVM). This happens when there is a defect in the lung and the air being positively pressured into the lungs escapes via that defect. This can’t occur unless you are providing positive pressure ventilation to a patient.

A tension pneumothorax can also happen as a result of trauma, barotrauma from a blast, or penetrating trauma that forms a valve. Now I know you all like to think of yourselves as sheepdogs, and the traumatic mechanism is the one you probably evoke as you are stuffing a handful of chest darts in your IFAK. 😉

It sucks, but does it blow?

What are the primary causes that can tear the lung due to trauma? The obvious one is an “open pneumothorax”, sometimes called a “sucking chest wound”. This happens when something has penetrated into the upper chest and left a hole (that might be able to reseal itself). Your respiratory system is a negative pressure system. When your diaphragm and intercostal (rib muscles) contract, your chest opens up (increases in volume). That increase in volume creates negative pressure that wants to equalize with the ambient air pressure. How it equalizes is by pulling in air from outside the body through the easiest available path. In a healthy intact human, that is through the mouth and nose. In a person with a hole in their chest, it might pull in through that hole, thus the “sucking” chest wound—which might seal up when the chest wall contracts.

The problem is that the air that has been sucked through the hole is not going into the lung (and that type of injury invariably collapses the lung as the air competes for space both inside and outside of the lung).

But here is the funny thing. A sucking chest wound is likely ALSO blowing. Meaning air is moving in both directions—air wants to flow through the path of least resistance. Even if that sucking chest wound is sealing up, enough pressure can be generated inside to overcome the “meat” seal and burp out. If the wound is “blowing” they CANNOT develop a tension pneumothorax. Same if the hole is big enough. In fact, the TCCC Guidelines a few years back noted that there were no deaths in OIF/OEF from open pneumothorax (by itself). In the civilian setting, it is even less likely.

Depending on the damage to the insides of the body, there is a LOT of space inside the thorax for air. One of my medic buddies reported that he was bagging a patient that apparently had bilateral pneumothorax–both lungs were leaking air from a gnarly car accident. This patient also had almost completely severed their trachea, and the medic somehow intubated across that gap and placed the tube correctly. Some gas exchange was still occurring in the lungs, thanks to that tube, but air was still escaping. The patient had also torn their diaphragm, and that air was moving into their abdomen and all the way down into their scrotum, enough to balloon them up. The pneumothorax never developed tension, nor did they consider decompressing the pneumoscrotum at the mid-testicular line.

Okay, so how does one develop a trauma-induced tension pneumothorax that needs to be decompressed? It would be from a sucking chest wound (that is NOT blowing), something that punctured the lung and then sealed the hole, or from a blast injury (torn lung tissue inside the sealed chest).

But how do you know?

Now for the million-dollar question. How do you know it is a tension pneumothorax? You really need to be able to confirm that it is tension pneumothorax before driving a giant needle into someone’s chest. Why? Because if they didn’t have a hole in the lung before, you just made one. You actually created the problem you thought you were solving. The best way to confirm a tPTX is with an X-Ray (or CT Scan). In the field, the best you can do is use a number of different data points to develop a thesis, and that requires some equipment that is normally not part of an IFAK.

If you carry a dart, also carry a way to develop an accurate diagnosis. (Photo by Hush Naidoo Jade Photography on Unsplash)

A tPTX takes a long time to develop—like 30-40 plus minutes (even up to hours). Using signs like “tracheal deviation” and “jugular vein distention” means you missed the problem a long time ago. By the time you start having vital sign changes and cardiac problems, the condition is pretty progressed, and is also what makes it “tension”. The tension is what is causing the vital sign changes since unacceptable pressure is being applied to the heart and vascular structures.

The tension pneumothorax begins a cascade. The heart problems manifest as decreased blood pressure since the heart can’t pump the blood through the circulatory system with the same force—hypotension. When the body isn’t circulating blood, the tissues in the body start becoming starved for oxygen—hypoxia. The brain tries to correct this problem by telling the heart to beat faster—tachycardia, and the lungs to “bellow” faster.

What happens if you get it wrong?

Fortunately, the complications from performing a needle decompression are pretty well documented.

- In over 90% of cases, the patient doesn’t improve. 9 out of 10 times it doesn’t help, assuming it is placed correctly.

- Roughly 25% result in MISSING the pneumothorax.

- 50% of the placements don’t effectively decompress the tension.

- Between 2% and 11% of the time (based on the study), a pneumothorax is CREATED.

It tapers off from there with things like hemothorax (filling up the chest cavity with blood), stabbing some other organ, and stabbing one of the major blood vessels. I’m not sure those odds make the juice worth the squeeze, especially for someone with a couple of hours of training on some baby back ribs…

If your first thought when seeing a rack of ribs is stabbing a 14 gauge needle into them, your priorities might be misplaced. (Photo by Alexandru-Bogdan Ghitaon Unsplash)

Frequently heard comments

Despite a tension pneumothorax being a relatively infrequent occurrence outside of combat, and despite it being a challenge for even well-trained medics to do consistently, effectively, and when actually needed, people still come up with reasons to justify carrying a chest dart and to intentionally stab an injured person in the chest.

Let’s hit this from the other side, for a kind of reductio-ad-absurdum argument. What about needle decompressing EVERY chest (both sides) with a potential mechanism (blast, penetrating chest trauma, etc.) and thready pulse? I mean we now no longer see a tourniquet as a last resort–why not the humble chest dart? Of course, that would be silly… A tourniquet is rarely (if ever) going to cause damage that will kill the patient if applied incorrectly and it certainly will not create massive hemorrhage in a patient that does not have a massive hemorrhage. On the other hand, if a patient does not already have a hole in their lung, and you jab a giant needle into it…

I can use percussion/direct ear on the chest/voodoo to confirm tension pneumothorax

The definitive way to diagnose tPTX is a chest X-Ray or CT Scan. You can develop a differential diagnosis by confirming the absence of breath sounds on the affected side along with hyper-resonance (from percussion). But you really need a stethoscope. Listening through a stethoscope is also not a simple skill, especially being able to accurately confirm diminished or absent sounds. There are different kinds, and more importantly, qualities, of stethoscopes out there. It is doubtful if you do carry one in your kit, that it is a $300+ dollar Littmann.

Percussion works great in a quiet classroom/exam room if you are well-practiced. In the field (or a field training environment) with the chaos of an event, good luck with that. Same with auscultating using a naked ear. Additionally, the hyper-resonance associated with tPTX is also generally found alongside jugular vein distension—a late sign.

If you can learn tactics from COD, you may as well learn medicine from games too… (The original uploader was Gene Hobbs at English Wikipedia., CC BY-SA 3.0 )

There are a few vital signs that may indicate a tPTX. Hypotension, hypoxia, subcutaneous emphysema, and tachycardia. For hypotension, you need to measure the blood pressure which means a blood pressure cuff and hopefully a stethoscope. For hypoxia, you really need a pulse oximeter (though cyanosis could be argued if you can rule out other causes). Tachycardia is easy to measure (and the pulse oximeter will do this for you as well).

Alongside that needle, do you also carry a stethoscope, blood pressure cuff, and pulse oximeter, in your IFAK?

I don’t know how to use one, but I carry a chest dart so someone else can use it

So you are going to trust some rando that walks up on a scene, decides you need to be decompressed and would be able to save your life only if there was a 3.25-inch, 14 gauge needle available? How is it they know you have a tension pneumothorax? See the previous section. Do you have the stuff they would need to confirm it in your IFAK?

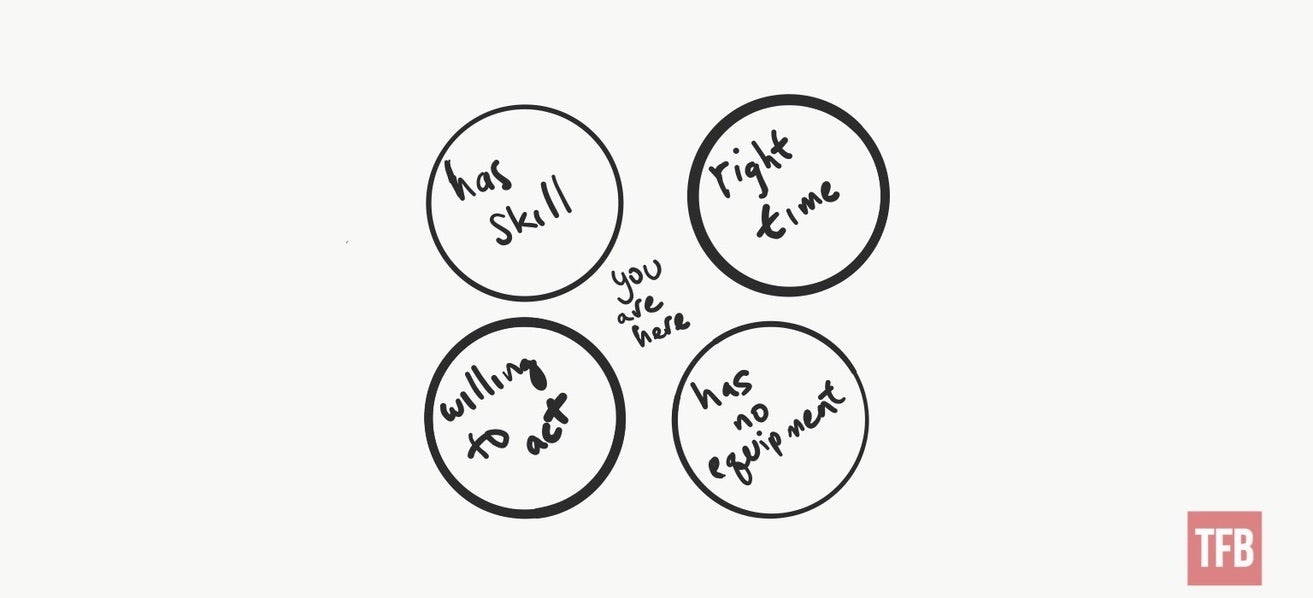

I would argue that someone that has the appropriate experience and training to CORRECTLY diagnose and decompress a tension pneumothorax, happens to be there at the exact time you need it, is willing to do the procedure knowing that they know will likely NOT be covered by insurance (or Good Samaritan laws), and also doesn’t have their own equipment is a Venn diagram of “not going to happen”.

Venn diagram I poorly drew showing the above scenario…

Or maybe you are running around the downtown of a large urban area (while wearing your plate carrier and carrying your IFAK) and a mass casualty occurs. Assuming you haven’t been detained by the authorities for looking out of place (unless there was an airsoft gear convention going on), you hop in and start helping. Nearby someone yells out that “I’ve got a tension pneumo here; anyone have a dart?”. Your cape unfurls, you rip open that IFAK, and chuck over that needle.

Tongue and cheek, yes, but seriously… Think through what actual scenarios you are likely to encounter and the probability of having a patient that will develop a tension pneumothorax and having another Good Samaritan on hand that can fix the problem.

It’s better to have it and not need it than need it and not have it…

I’d love a portable trauma suite fully staffed with trauma specialists, but the reality is…

In wilderness medicine, we discuss the concept of “Ideal vs Reality”. Ideally, I would like to have instant access to all of the specialized equipment I could and be able to deploy instantly as needed. The reality is that I can only carry a limited amount of stuff without looking like a crazy person (depending on the context) and drawing inappropriate attention. The reality is that I am likely to encounter only a small subset of known (and treatable) medical problems in normal life.

At a certain point, just bring all the things… (Photo by Mick Truyts on Unsplash)

100% of the people on the planet will experience cardiac arrest at least once. That doesn’t mean I carry an AED around with me everywhere.

I can think of many different things that would make my first aid kit long before a decompression needle. No one that has ever dealt with a traumatic medical emergency has ever said, “You know, I just had too much gauze available…”

Part of providing medical assistance is having good judgment. Good judgment includes understanding the injuries that are most likely to happen and having the ability to treat those injuries. Good judgment is also staying in your lane (within your training and experience).

It doesn’t take any space in my IFAK

You could fill an entire IFAK container with equipment that “doesn’t take any space”. Don’t let equipment serve the role of magic talismans that replace training and skills. The most important piece of equipment is your brain. Fill THAT with the ability to determine if a problem is serious or not serious and if the problem is getting better or worse.

In your IFAK, you should carry, at a minimum, tools to help you deal with IMMEDIATE life-threatening injuries. Injuries that will kill you right now. Tourniquets (a real tourniquet that applies mechanical advantage and is backed by science, not a fancy rubber band). Compressed gauze. Chest seals. Be wary of any kit that does not include those items.

Tension pneumos take time to develop. The biggest problem is that needle decompression is done too often/too early by most medics. Because of the inability to definitively diagnose tPTX in the pre-hospital setting, needle decompression should only be done as a Hail-Mary when the patient is crashing/coding. In those situations–meaning mechanism of injury that would create a tPTX coupled with respiratory failure and peri-code (that moment right before the patient “codes”)–needle decompression is probably not going to make things worse.

Conclusion

I doubt I have swayed the opinions of those that are ardent believers in chest darts, and that is fine—it is up to you to assess the risk you are willing to accept to support an intervention that is rarely needed, and which comes with potentially disastrous outcomes if done inappropriately. For those that may have been fence-sitting, yet only intrigued by the sexy appeal of a stabby device in your medkit, I hope that you now have a little more knowledge and can make a better-informed decision if it is right for you.

A true operator’s kit. Snatching souls from the Angel of Death one talisman at a time. (Tongue-in-cheek kit photo provided by Michael M. of Triarii Protective Services & Consulting)

Keep in mind a peer-reviewed study found that even “60% of emergency physicians misidentifying [sic] the correct site”. Other studies note “the success rate for paramedic decompression of suspected tension pneumothorax using this approach is low varying from 18% to 62% due to failure of the needle to enter the pleural cavity, misplacement or kinking or blockage of the catheter”. Those are pretty big fail numbers for people that have significant training and more than likely have performed these skills on real patients.

In any case, I do hope this rant has helped inform and entertain the rest of you. I expect/hope the comments will get pretty spicy so stay tuned and microwave your popcorn.

Here are some references to show we aren’t just pulling this out of an orifice. Feel free to nerd out if you wish.

Tension pneumothorax: How capnography and ultrasound can improve care:

https://www.ems1.com/ems-products/capnography/articles/tension-pneumothorax-how-capnography-and-ultrasound-can-improve-care-YWQsd1S1HuvwBDPr/

Treatment of Thoracic Trauma: Lessons From the Battlefield Adapted to All Austere Environments: https://www.wemjournal.org/article/S1080-6032(17)30061-3/fulltext

Tension pneumothorax—time for a re-think?:

https://emj.bmj.com/content/emermed/22/1/8.full.pdf

Needle thoracostomy may not be indicated in the trauma patient: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0020138301000821

BET 2: Pre-hospital finger thoracostomy in patients with chest trauma: https://emj.bmj.com/content/34/6/419.1

Complications of needle thoracostomy: A comprehensive clinical review: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4613415/

Your Privacy Choices

Your Privacy Choices