There is a lot of internet chatter about whether or not it is safe to shoot a “low number” Springfield M1903 bolt-action rifle. When I say “a lot,” I mean a whole lot: a Google search of the phrase “1903 safe to shoot” brings back 20.2 million hits, including 148,000 videos. Now, not all of those are going to be specific to the problem, but even if just 10% are, well then, man, that’s a lot of bandwidth on this topic!

Truthfully, people have been discussing the safety of M1903 rifles for more than 100 years. Concerns about the guns began at the peak of their production when their reliability truly was a matter of life or death for the soldiers fielding these arms.

In the last six months of 1917, eleven M1903 rifles were reported to have shattered – yes, shattered – and caused one severe and ten minor injuries. Even though production had shifted into overtime since the US involvement in World War I in April of that year, production was halted until the problem could be identified and resolved.

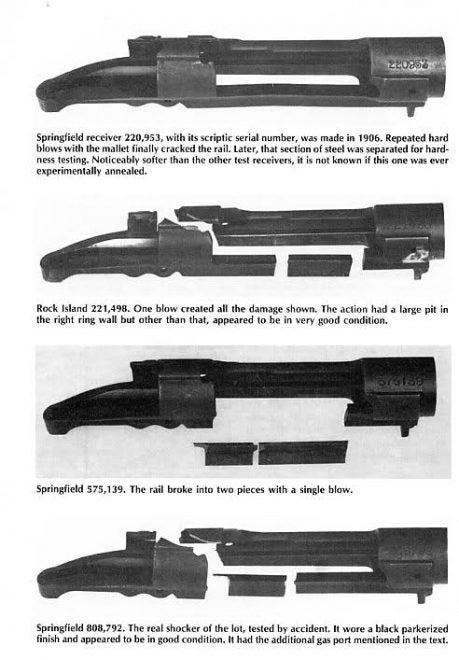

The issue was found to be with the heat treating process. Specifically, armory employees in charge of the process were using the “eyeballing” method to measure temperatures. Heat treating is exceptionally important to the rifle’s success. Too little and the metal won’t be hardened; too much and it will become brittle. The latter issue is what was being examined.

General Julian Hatcher was in charge of the investigation and what he discovered was shocking. On cloudy days when the sun did not interfere with the ability to see the metal’s true color in the fire, the “right temperature” was deemed to be 300 degrees cooler than on a sunny day when colors were harder to see.

That 300-degree difference on a sunny day was enough to overheat the metal, thereby making it brittle and susceptible to failure.

The 12-year period between 1917 and 1929 recorded a total of 43 injuries due to the brittle metal. Three men each lost an eye, six more received “serious” injuries, and the remaining 34 injuries were deemed “minor.” Still, even a minor injury is a major problem for the person receiving it.

To remedy the situation, the receivers (and the bolts) made from now on would undergo a double heat treatment with their temperatures being measured by pyrometers instead of a visual determination. The double heat treatment for receivers from Springfield Armory was in place by serial number 800,000 and by serial number 286,507 for those made at Rock Island Arsenal. Anything below those numbers are considered to be “low number” guns that are dangerous to fire.

By the end of 1927, it was recommended that the US Army withdraw the approximately 1,000,000 “low number” guns currently in service and discard them because it was not feasible to re-heat treat them. This was unacceptable to military leaders based solely on the numbers. Less than 60 failures had been reported out of 1,000,000 rifles. That’s a fail rate of six-thousandths of one percent.

The risk was deemed acceptable and orders went out that no more “low number” guns would be issued, but that those already in service would not be recalled. When they were turned in for repairs at a later date, the guns were to be set aside as a war reserve and not reworked or reissued. This would lead to all of the guns being removed from service eventually – not immediately.

Of course, each branch of the military was free to make its own judgment call. The Marines did not follow the Army recommendations, and they kept all of their 1903s in service up until 1942.

Soldier with the 36th Infantry holding a later M1903 in 1943.

Rifles made at Springfield beginning with serial number 1,275,767 and at Rock Island with serial number 319,921 no longer received the double heat treatment because the receivers and bolts were now being made from an improved nickel steel.

To my knowledge, the last solid data available on 1903s that failed and caused injury of some kind is from 1929, making it now 90 years old. Anyone who was alive and witnessed such an event is long gone. I’ve never met an “old-timer” who has encountered one that was cracked or had failed. In my professional life, I’ve personally handled countless M1903 rifles with low serial numbers and have never observed one with a compromised receiver.

Until now.

I recently picked up an M1903 rifle made at Rock Island in 1909. The serial number fell more than 100,000 numbers below the safe range, but I bought it anyway. After all, you’re just as likely to die by receiver failure as you are for every 1,500 miles you travel by car. I used to commute more than 30,000 miles per year, so I was OK with those odds.

Cracks in an M1903 receiver made at Rock Island in 1909.

That is, until I put the gun on my workbench and took it apart for a good cleaning before heading out to the range. That’s when I saw it: a crack on the left side of the receiver, about one-inch in length. No – couldn’t be! I grabbed my lighted magnifying glass to get a better look. Sure enough – a crack! I ran my thumb over it and my thumbnail got hung up on the crack.

Cracks in an M1903 receiver made at Rock Island in 1909.

Damn. I shot a quick note off to the seller explaining what I found. He apologized for not spotting it first and told me to bring it back and exchange it.

The next day, I was looking the rifle over again when I spotted another crack. This one should have been more obvious, given that it was on the top of the receiver, but the lighting wasn’t right and I hadn’t spotted this half-inch crack the day before.

Cracks in an M1903 receiver made at Rock Island in 1909.

Once I had spotted the cracks, I couldn’t unsee them. So how had I missed them before? Part of it is an issue of lighting. The other part is an issue of the environment. Standing in a gun shop or a gun show aisle looking over a gun isn’t exactly a place that lends itself to a careful and thorough examination.

Now, I’ll be the first to admit it: I got lucky. I didn’t do my initial due diligence and I bought a gun with a fatal flaw. Thankfully, the seller was reputable and honest, so my exchange was quick and painless. The two guys who run the shop both stated that they’d never seen one before, and were conflicted about actually holding evidence of it. On the one hand, they now had physical proof of the problems; on the other hand, they couldn’t in good conscience sell the gun, so they’re out some money.

It’s really kind of crazy when you think about it: between the three of us, the guys in the shop and I have well over a century in the gun business with tens of thousands of guns bought and sold and handled and examined … and none of us had seen one before now.

So, here are my takeaways from this:

- Just because you haven’t seen something yourself doesn’t mean it doesn’t exist.

- Yes, the “low number” 1903s really do have problems, regardless of your own prior personal experience with them.

- Always give a thorough inspection to any gun you’re intending to purchase.

- To that end, always buy from reputable sellers who will own up to their mistakes and make things right.

- Learn from your mistakes and move forward.

Now, if you’ll excuse me, I’ve got another M1903 to go shoot!

Your Privacy Choices

Your Privacy Choices