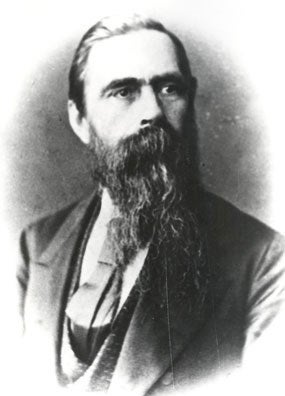

While you’ve probably never heard of him, James Henry Burton is one of the – if not the most – influential gunsmiths of the 19th century. Under his direction, millions of arms made in three countries on two different continents played an essential role in the Civil War regarding how it was fought and how it changed military tactics forever.

Born in rural Virginia in 1823, Burton attended West Chester Academy, a premier prep school in Pennsylvania. At age 16, he moved to Baltimore, where the famed Baltimore & Ohio Railroad was headquartered. While there, he spent five years as an apprentice in a machine shop, learning valuable skills that would pave the way for his future.

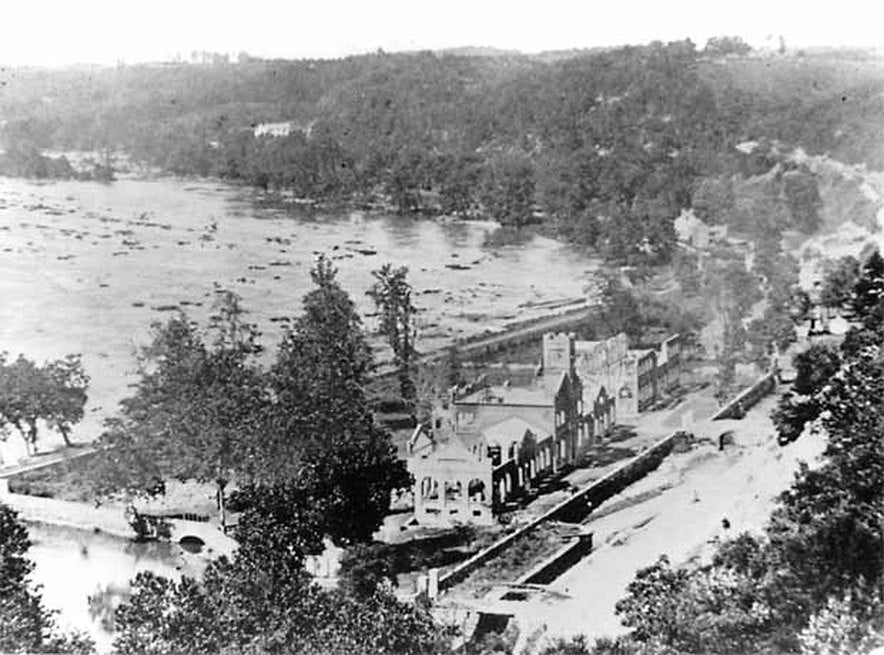

Town of Harpers Ferry in 1859. Courtesy National Park Service.

In April 1844, Burton took a job as a machinist at the Harpers Ferry Armory. Coincidentally, the B&O Railroad ran through Harpers Ferry, so part of Burton’s ties to Maryland followed him to Virginia. Burton’s obvious skill led to a promotion within a year when he became the foreman of the Rifle Factory Machine Shop. Here, he met John H. Hall of Hall’s Rifle Works, who was responsible for bringing the concept of machined, interchangeable parts to Harpers Ferry. The two were likeminded, and Burton soaked up Hall’s passion for innovation. Within four years, he was again promoted, this time to Acting Master Armorer.

Ruins of Hall’s Rifle Works. Courtesy National Park Service.

Though the most iconic projectile of the Civil War – the Minie ball – was invented in 1848 and named after Captain Claude Etienne Minie, its final form was influenced by James Burton. Within a year of its design, Burton began working on ways to improve Minie’s creation. It took years of hard work, but it all paid off when the U.S. Army adopted Burton’s improved Minie ball design in 1855. When the Civil War broke out in 1861, soldiers on both sides of the Mason-Dixon Line carried Burton’s bullets in their cartridge boxes.

Burton’s drawing of the Minie ball. Courtesy National Park Service.

Burton left Virginia in 1854 and moved to Massachusetts, where he took a job at the Springfield Armory. In addition to working at the Armory, he was also employed by the Ames Manufacturing Company. Ames provided Harpers Ferry and Springfield with machinery for arms manufacturing. They also made some of the most famous swords used in the Civil War.

It should come as no surprise that Burton found himself, once again, right in the middle of more arms innovation. Thomas Blanchard’s lathe used to faithfully duplicate gun stocks had been improved upon by Cyrus Buckland in 1853. With this new design in hand, Burton drafted plans for a new set of gun-stocking machines ordered from Ames by the British Board of Ordnance.

Always thinking one step ahead, Burton had inquired about working for the British Ordnance Department before he moved from Virginia to Massachusetts. It turned out to be a smart move because the final answer took a year to materialize.

Springfield Armory is now run by the National Park Service. Author photo.

In June 1855, Burton accepted a five-year contract at the Royal Small Arms Manufactory in Enfield, England. One of his first tasks was to set up new machinery that had just arrived from the United States – more specifically, the Ames Manufacturing Company in Massachusetts. In a short time, he was promoted to Chief Engineer.

Under Burton’s direction, Enfield produced hundreds of thousands of the Pattern 1853 rifled musket, which would become one of the primary long arms used in the Civil War, particularly in the Confederacy.

In 1856, Burton crossed paths with renowned toolmaker (and soon-to-be-gunsmith) Joseph Whitworth. Cut with hexagonal rifling, Whitworth believed his new design would create a rifle that was superior to any other currently on the market, especially at long distances. Burton attended trials for the Whitworth rifle and was thoroughly unimpressed. Nonetheless, the Whitworth rifle would become a prized possession by Confederate sharpshooters in just a few years.

Things were going well for Burton at Enfield until October 1859, when he and his wife Eugenia received a letter from her parents, George and Mary, regarding John Brown’s Raid.

Joseph R. Anderson, owner of the Tredegar Iron Works in Richmond, Virginia, tapped Burton to oversee his contract to resupply and reactivate the Virginia Manufactory of Arms. (It would be renamed the Richmond Armory in 1861.) Burton agreed, and he returned to Virginia in the fall of 1860.

Immediately after Virginia seceded in April 1861, Harpers Ferry was set ablaze by Federal soldiers to keep the arms and machinery out of the hands of the South. The arsenal, along with 15,000 weapons, was a total loss. Flames in the armory, however, were brought under control and the machinery contained within survived.

Ruins of the Richmond Arsenal. Public domain – Wikipedia.

In June 1861, Burton became Superintendent of the Richmond Armory, where he oversaw the manufacture of arms on tooling and machinery confiscated by Confederates at Harpers Ferry. As it turns out, the machinery was absconded with under the direction of Burton himself.

As 1861 drew to a close, Superintendent Burton became Lieutenant Colonel Burton, and he took command of production at all of the Confederate armories. By summer 1862, Burton left Virginia and headed for Georgia, where he had been instructed to establish a new armory. With land prices on the rise, he chose Macon over Atlanta.

A year later, Lt. Col. Burton sailed to England, hoping to obtain new equipment to complete the armory in Macon. It took almost a year after Burton returned to Georgia for the machinery he so desperately needed to be shipped from England. The material finally arrived in Bermuda near the end of 1864. The machinery sat in Bermuda for months, waiting for the right opportunity to be smuggled through the Union blockade.

Then, on April 9, 1865, General Robert E. Lee surrendered to General Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox Court House. With that, the Civil War was over.

Burton was held prisoner until October 1865, when he signed the Oath of Allegiance and received a pardon by President Andrew Johnson.

The next eight years were busy ones: Burton went back to England to run a new armory until 1868 when he moved back to Virginia. Then, in 1871, he headed to England again to work on an arms contract between Britain and Russia. Finally, he came back to the United States in 1873 and settled near Winchester, Virginia. Here, Burton spent the rest of his days farming until his death in 1894. He is buried in Winchester’s Mount Hebron Cemetery.

Your Privacy Choices

Your Privacy Choices