In the last episode, we discussed how the most ballistically efficient projectiles are the longest, most slender ones, with the highest sectional density. This naturally leads to the idea of using a super long, rod-like projectile which would in theory have excellent ballistic characteristics… But there’s a problem with that: Unfortunately, modern rifle projectiles are spin-stabilized, and there’s a limit to how long of a projectile can be and still be stabilized by gyroscopic forces in that manner (that limit is about 7 calibers long in theory, more like 6 in practice). This means that to successfully stabilize the longest possible projectile with the highest possible sectional density, another method is needed. The most popular alternative – and the one used in arrows, darts, APFSDS tank projectiles, and today’s topic, flechettes – is fin-stabilization.

Fin-stabilization is a form of drag-stabilization, where the projectile is shaped in such a way that the drag keeps it properly oriented throughout its flight; in fin-stabilization this is accomplished by adding fins. The result is a small arrow-shaped projectile with fins at the rear (called a “flechette”), virtually always coupled with a sabot. In this configuration, a lightweight flechette can be fired at extremely high velocity on a small amount of propellant, while producing ballistics that put even the flattest-shooting wind-buckingest conventional rounds to shame. In addition, the projectiles – having very high sectional density and striking velocity – possess excellent penetration characteristics. Also, very long, lightweight projectiles (~10 gr/0.65 g) can be used, allowing a dramatic reduction in ammunition weight versus conventional designs.

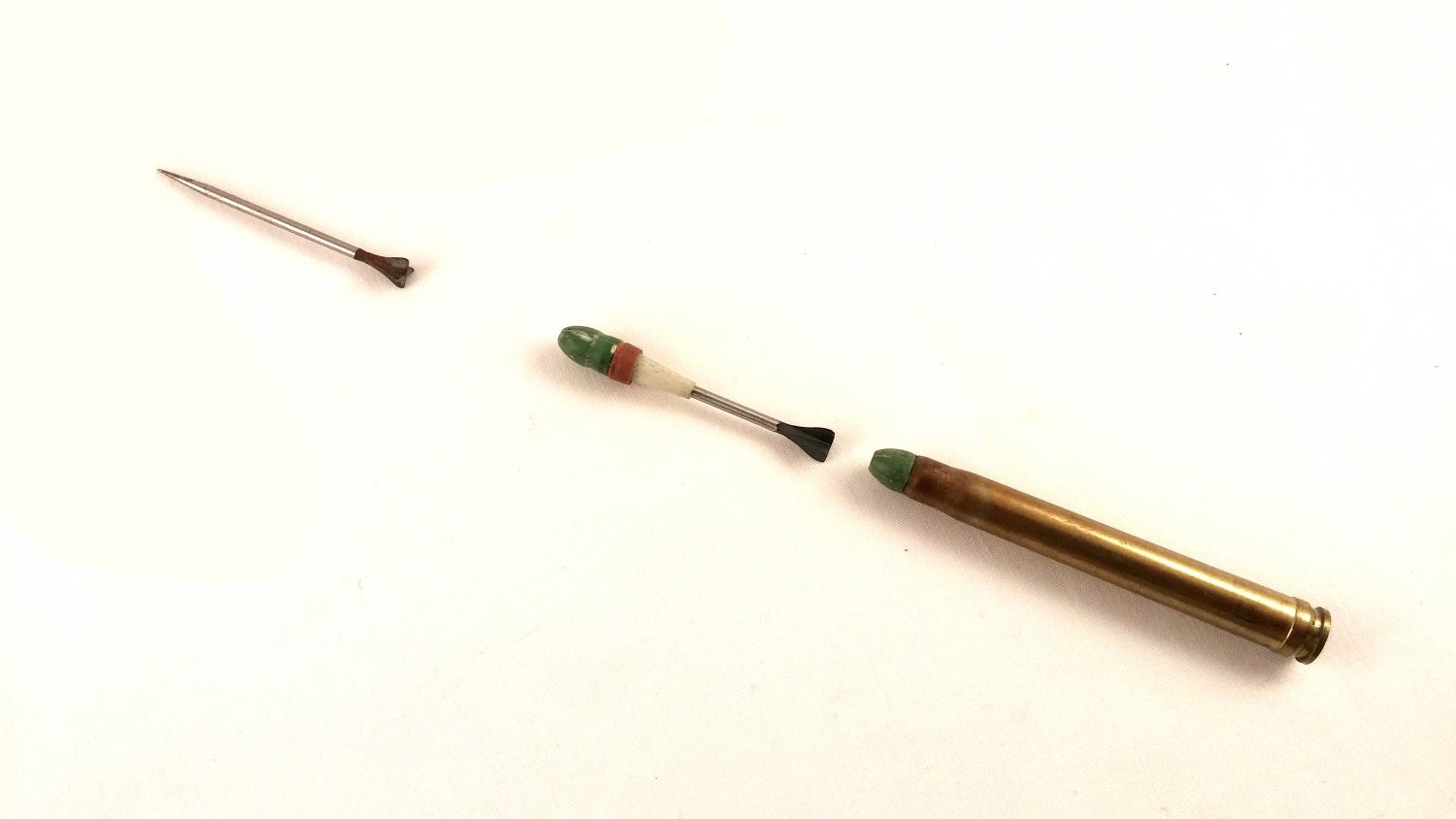

This photo illustrates how an SPIW-style flechette works in conjunction with its disintegrating sabot. The sabot and flechette are fired from the case as a unit, but once this leaves the muzzle, the sabot disintegrates, leaving only the flechette to travel to its target.

Flechettes may have excellent ballistics, but they also have some limitations. Small flechettes retain energy well, but due to their small diameter do not create very large shockwaves as they pass a target, and therefore have poor suppressive capabilities. Their low volume, too, is a hindrance to their lethality, although flechette projectiles have proven to distort and bend, “J hooking” readily in tissue. Also, for very high velocity flechettes (over 4,000 ft/s), the projectile itself must be able to withstand the extreme acceleration of firing, which was a problem for the SPIW program of the 1960s and 1970s. Further, the manufacture of very small flechettes that could withstand high acceleration forces never became very mature, and historically small flechette ammunition was relatively expensive to produce.

Still, it’s not difficult to imagine a weapon firing low-mass, high velocity flechettes coupled with a lightweight case design and an extremely high rate of fire. Such a device could possibly compensate for the low effectiveness of its individual projectiles simply by firing much more of them than a traditional weapon, and the extremely low ammunition weight would facilitate this prodigious expenditure.

Your Privacy Choices

Your Privacy Choices