[ Steve says: This guest post was written by a practicing patent attorney with no connection whatsoever to the Mossberg AR-15 trigger patent lawsuits. ]

With the whole Mossberg drop-in trigger stories of the last week I have been asked to give a brief overview of what a patent is, and how it works. Since this is an extremely complex topic and a whole specialized profession has been built around, I can’t describe every facet, but I hope to be able to give sufficient detail that readers will be able to look at patent cases more critically and in a more informed manner.

So what is a patent?

In short, it’s a limited monopoly right to prevent others from exploiting an invention, for up to 20 years from filing the application. There are some small exceptions to this, but don’t worry about them. It is a piece of property that can be bought, sold, licensed and so on. If it couldn’t be, it would have no value to someone who doesn’t want to, or can’t, produce themselves.

It’s also an exchange. In order to be granted the patent, you have to disclose to the world how your invention works. This enables others to find out about it and build on it. So we exchange information for a time-limited monopoly right.

What is a patent not?

It’s not an automatic right to exploit the invention yourself, since you can be within someone else’s broader patent. Example (please suspend disbelief): I’ve just invented the chocolate chip cookie, and I’ve been granted a patent to it. I can’t sell chocolate chip cookies, however, if there’s someone else who holds a similar patent protecting cookies in general, but not ever mentioning chocolate chips (he hadn’t thought it possible, thinking that they’d just melt into mush).

So I’m stuck. I’m blocked. But, chocolate chip cookies are better than just plain cookies. I can prevent Mr. Cookie from selling chocolate chip cookies, just as he can prevent me from selling any cookies at all. But, unless Mr. Cookie is totally unreasonable, he’ll want to be able to sell the improved cookies, so we’ll trade: he’ll let me produce chocolate chip cookies, if I let him produce them too. A “cross-license”, which is a win all around! Then the marketing guys can make a fortune on ad campaigns….. But I digress.

It’s not a right that’s unlimited in time. Once it expires, it’s gone and anyone can use the invention for profit.

What does a patent have to be?

To be valid, a patent has to claim something that is new, and is not obvious, and describe it well enough that someone else can replicate it. Note that it is what is claimed that counts – it is not some random statement in the description, or some vague concept, but the independent claims. These are claims that are not “according to” an earlier claim. “Dependent claims” refer to other claims and add more features and serve as more specific, narrower, claims as fallback positions in examination or validity proceedings, and have some other minor functions. Don’t worry about them – if you’re not infringing an independent claim, you’re not infringing a dependent one either, by definition.

So, when you’re looking at a patent, start with the claims first, even though they’re at the end. Because it’s these that define what is protected.

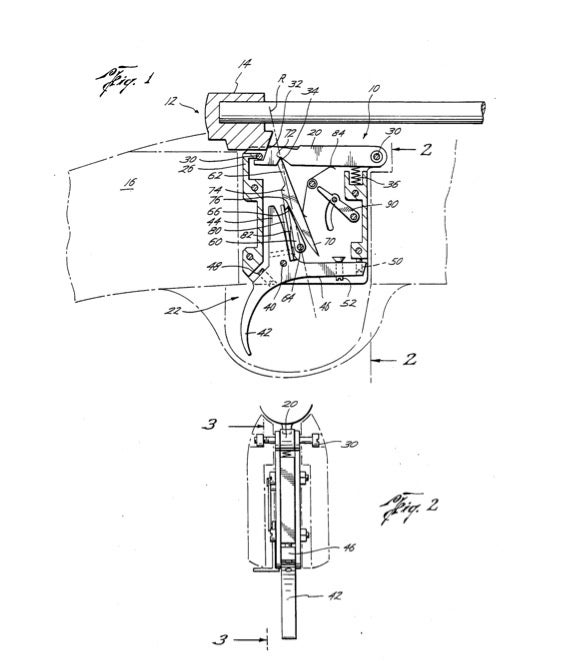

Now, often the claims are super dry, crazily abstract and hard to follow. Then you need the description and the figures to work out what’s going on.

“New” means “not literally disclosed before”. This is fairly simple – does one variant in a document, or a product, disclose all of the features of a claim? If yes, then it’s not new. If no, then it is and we move on to obviousness.

Obviousness, or “inventive step”, is trickier, more subjective, and each country determines it a bit differently. In brief and over-simplifying somewhat, in the US, if several documents disclose all the features of a claim and the skilled artisan (who is not an inventor) would put them together to arrive at the claim, then it’s obvious.

Now, let’s put this into the context of the Mossberg patent, US 7,293,385 as granted, just taking the simplest and broadest independent claim, number 1. All the information below is in the public domain, downloadable from the USPTO Public PAIR service.

Now what a patent attorney does in this situation is split the claim down into its original features, and compare them with the prior art, often in the form of a table. For reasons of space, I’ll just reproduce the claim, with the features known in e.g. a random pinned-in trigger pack in italics:

- A trigger group module for a firearm, the firearm including a receiver that defines a trigger group receiving area between a first receiver side wall and a second receiver side wall, the trigger group module including:

(a) a module housing adapted to be inserted to an operating position in the trigger group receiving area, the module housing having a lower extremity that is located above a lowermost edge of the first receiver side wall and a lowermost edge of the second receiver side wall when the module housing is in the operating position;

(b) a number of trigger group components mounted within the module housing;

(c) a first pin receiver positioned in the module housing so as to align with first pin receptacle openings of the firearm when the module housing is in the operating position, the first pin receptacle openings defining pin support surfaces formed in the first receiver side wall and the second receiver side wall; and

(d) a first module pin mounted in the first pin receiver on which one of the trigger group components is supported in the module housing, the first module pin including an opening that aligns with the first pin receptacle openings of the firearm when the module housing is in the operating position.

Firstly, note how if we take the HK trigger pack, or the Petter-type of the SIG P210, don’t even have all the features in italics, since they’re not pinned in, so don’t have feature (c) at all.

Now, the features in bold are the key to this patent. What this claims, in plain English, is the hollow pin arrangement which aligns with the existing openings in the receiver and also supports a trigger group component (such as the hammer, for instance, although this is not specified). In the first round of examination, nobody presented a document showing this feature, and it seems to be a clever way to simplify mounting using existing holes, to save space in the module since no extra pin pass-throughs are needed, and any number of things that can be thought up by a half-competent patent attorney.

However, if someone turned up a document showing such hollow pass-through pins, then Mossberg would be in a heap of bother.

A first re-examination (control number 90013200 at the USPTO if anyone is interested), presented this document (belonging to Jewell):

Hmmm. Part 30 at first glance looks suspiciously like a hollow pin arrangement like in the claim. But the Examiner disagreed, stating that the document “shows a mounting pin 30, but the pin is solid and has no opening. The sleeve that the pin (30) passes through cannot meet the claim limitations of the pin, as it is not supported by pin support surfaces formed in the receiver side walls. None of the other cited references provide a teaching of a pin having an opening which aligns with openings in the firearm”.

This is where it gets interesting (and complicated). In view of the complexity of the case, I won’t go into details.

But in essence, the novelty of the independent claims is not in question, contrary to some very strongly-held beliefs in forum comments. Sorry, guys. If you know differently and can provide concrete evidence, then the USPTO would like to know. So write them.

The examiner relies on the combination of the Jewell document with both US 3,707,796 showing a hollow pin and US 5,904,132 showing the position of a module in a receiver to assert that the McCormick patent is obvious, through a somewhat complex reasoning. However, this relies on the Examiner considering that the cavity in the stock 16 of Jewell is in fact part of the “receiver”… (surely that depends on what the meaning of “is” is…) And combining three documents, which is already getting onto shaky ground.

In case anyone spots it, there’s also a document mentioned in the proceedings which does show a hollow pin arrangement (US 7,421,937), but this is “sworn behind” and is disqualified as prior art (technical issues relating to dates and ownership of the invention. Don’t worry, just accept it’s out).

Anyway, without going into gory details, the job of Mossberg’s patent attorneys now is to try to get around the Examiner’s arguments while still covering the infringing products. They’ve been amending the claims, and are now pushing independent claims limited to modules containing two of these hollow-pin arrangements (the latest version at the time of publication was filed on April 21, 2016). A subsequent office action is rather negative though.

We’ll see how this develops – I don’t want to call the final result one way or the other at this point, since the case is complex. And once the re-examination is over, there are appeals and so on, so it could be a long while before it’s settled.

Your Privacy Choices

Your Privacy Choices