The next few installments of my Light Rifle series of articles will cover in detail the development of the two calibers that shaped the NATO rifle trials until 1953: The .280 British and the .30 Light Rifle, the latter of which – spoiler alert – subsequently became the 7.62x51mm NATO in 1954. The subsequent rejection of the more intermediate .280 British as the standard NATO rifle cartridge caused considerable controversy in the UK, and many experts today believe that it was the superior choice for a standard round versus the much more conventional .30 Light Rifle. Advocates of the .280 British lament its rejection as being politically-driven, but – while there’s considerable truth to that notion – there is another side to the story. One critical document from this period is A Comparison Test of United Kingdom and United States Ammunition for Lightweight Weapons, from 1950.

.280/30 Ball compared to .30 Light Rifle Ball, AP, and API, as used in A Comparison. Photo by DrakeGmbH, used with permission.

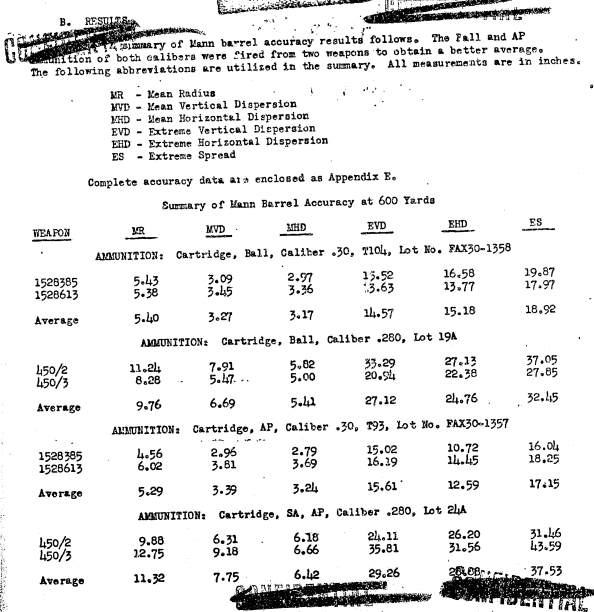

The document illustrates the more advanced stage of development of the .30 Light Rifle cartridge (the program for which began in 1944) versus the .280 British (starting circa 1948), particularly in the accuracy results:

In accuracy tests conducted as part of the February – May 1950 evaluation of the two rounds, the .30 Light Rifle consistently grouped with nearly half the dispersion of the British .280 cartridge. Further, the .30 Light Rifle was also shown to be superior with regards to penetration and trajectory, with the .280 pulling ahead in API ignition and tracer and observation round consistency.

The development of .30 Light Rifle illustrated in a photo. Photo by DrakeGmbH, used with permission.

The poor showing of the British round would prove to seriously hamstring the push for its adoption. While many other factors were in play, it’s likely that one of the major factors in the US officials resistance to the .280 caliber round was its inferior performance in these and other tests. While today, we know their standards were unrealistically high for modern warfare, the rejection of the .280 was a little more complicated than simple “Not Invented Here” syndrome.

Your Privacy Choices

Your Privacy Choices