If you read the previous two installments on how to order from the CMP, then you have a good idea about how to get eligible, fill out your paperwork, and send in your packet for a Field- or Service-Grade M1 Garand rifle. Now what? Once the waiting is done, and your rifle arrives at your doorstep, you have received a shiny new example of Patton’s “deadliest rifle in the world”.

Actually, although new to you, what you got was a mixmaster M1 Garand, probably with a brand new wood stock and handguard, and the rifle may have some functioning problems or imperfections. The CMP does the best they can with the parts they have, but ultimately your rifle is assembled from parts all over the specification, and it may need a little tender love and care to become all it could be. A well-tuned M1 is a truly great rifle, and an excellent range gun, but how do you get from here to there?

Some folks may be perfectly happy with a totally stock CMP M1, but my goals for my CMP M1 were threefold: To fix the minor mechanical issues my rifle had, to perform minor accurizing to my rifle, and to change its appearance to be closer to a historical M1. With regards to this last, the new wood stocks the CMP M1s come with are fine pieces of hardware, but don’t closely resemble military surplus gunstocks. Instead of buying and accurizing a military gunstock, I decided to accurize and modify the new CMP stock with historical processes to achieve the functionality and appearance I wanted. This post will cover most of the functionality and accurizing modifications, while Part 4 will cover how to achieve the historical look.

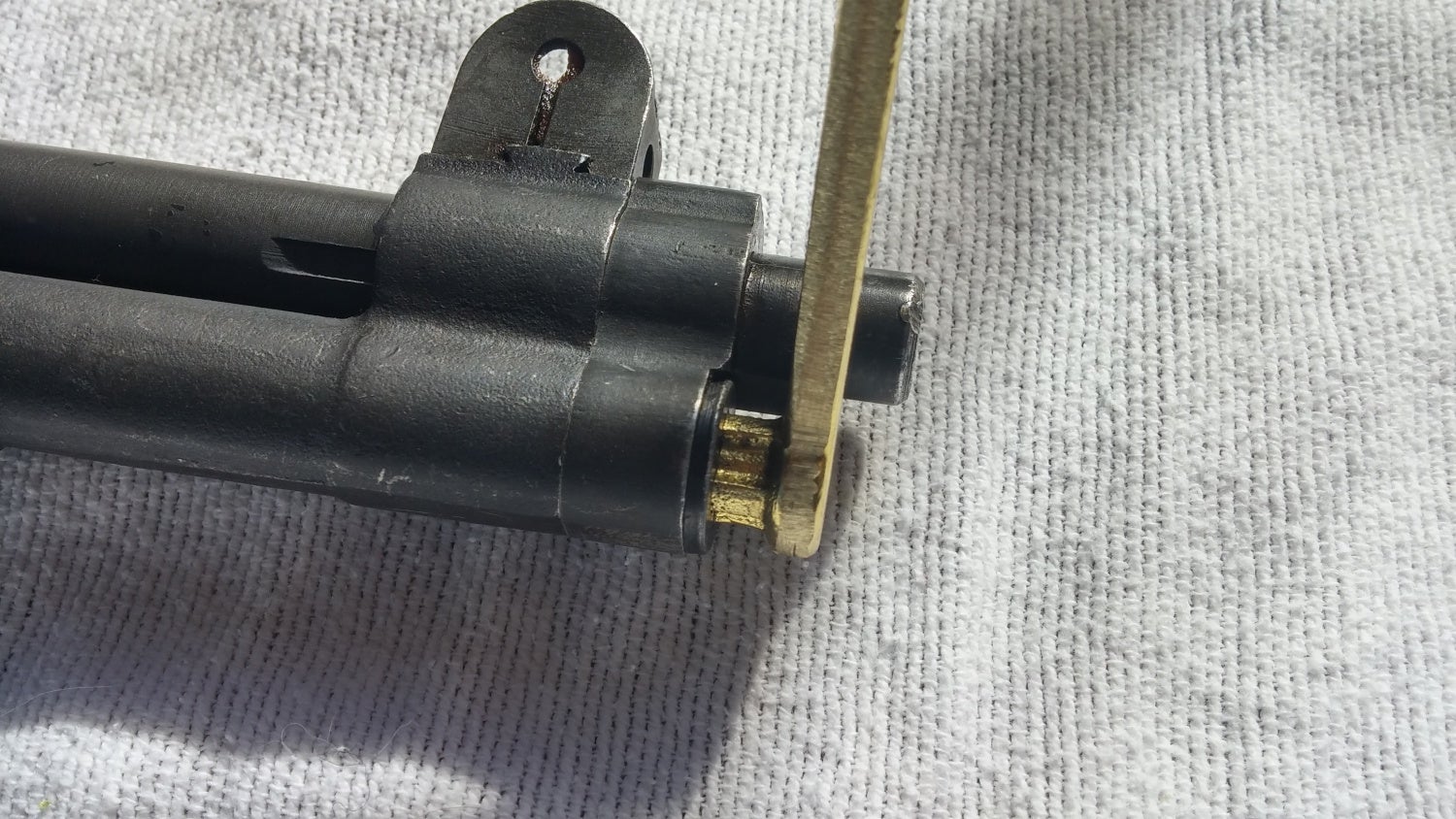

Now, functionally, the M1 rifle is sort of like a chain. Every part in it has a job, and they’re all linked together, and most importantly if one part isn’t working right, the whole system stops working right. That means troubleshooting the M1 can be a bit of a hassle. The first mechanical problem I noticed was difficulty in inserting an en-bloc clip. Research online suggested that the problem was the follower arm not being able to move far enough downward, which meant a great deal of force was necessary to seat a clip fully until the clip retaining latch clicked. The counterintuitive fix was to check the tab on the bullet guide for peening. A quick inspection showed that my M1’s lockwork pin was very difficult to remove, and the bullet guide was indeed peened:

Note the peening on the tab at the very top of the bullet guide in this image. This peened portion pushed the lockwork out against the receiver, preventing the follower arm from moving far enough to easily seat an en-bloc clip.

A quick application of some emory cloth removed the peened portion and freed up the lockwork retaining pin and allowed easy insertion of en-bloc clips.

Next, I moved on to cleaning up the wood around the functioning areas. To do this, I needed to purchase some supplies online; the total kit is shown below:

M1 Garand stocks were historically sanded by hand with 100, 120, and 150 grit cloth, and were finished with raw linseed oil which I purchased from GarandGear.com) which gives surplus stocks their reddish color. In addition, I chose to purchase “Gunny Paste”, a sealing wax, to help preserve my M1 against the humidity here in Louisiana. From AmmoGarand.com, I bought a gas plug wrench and a standard GI sling. The historical lubricant for the M1 was Lubriplate 130A, which I purchased direct from the manufacturer in 14 oz quantity because no smaller size was available. I probably have enough L130A to last me a lifetime, now, but at least my Garand will be authentically lubricated. Clearly, I should have bought mutton tallow, instead!

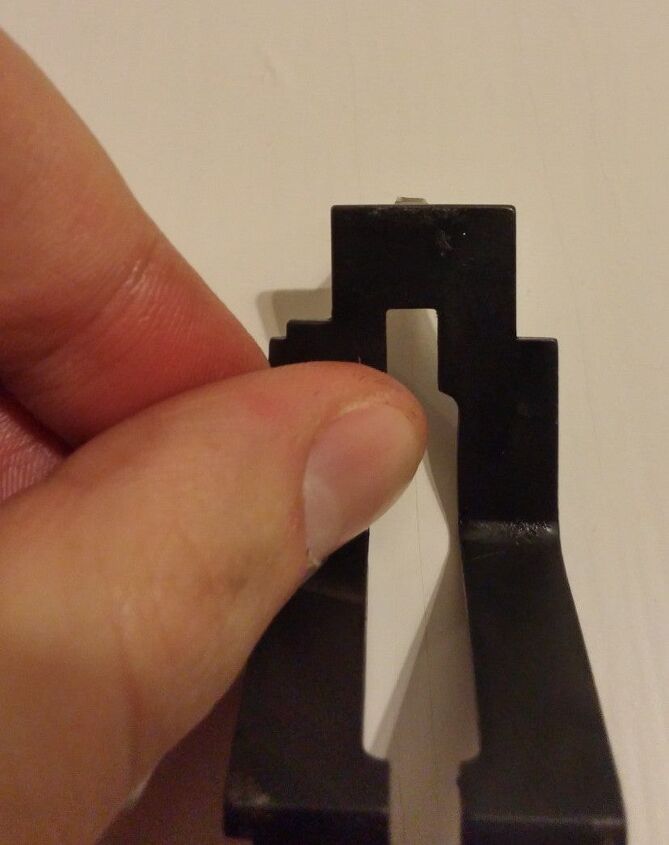

My M1 has an early-style trigger guard, so I made use of an old broke plastic punch as a disassembly tool to remove the fairly tight trigger pack:

The first thing that became obvious upon disassembly was that my operating rod was bent slightly side-to-side (M1 operating rods by design have a natural top-to-bottom dogleg to them. A side-to-side bend is common, but not by design). For the sake of both functioning and accuracy, the operating rod should not contact the wood stocks of the firearm at all. A very helpful guide to stock fitting is available on the CMP forums, written by user tinydata. Instead of undertaking the challenging task of bending my original oprod, I decided to clean up the wood to allow the best functioning possible. The first step in this was to sand the inside left edge of the front handguard so that it wouldn’t contact the operating rod. To remove the front handguard, I used the gas plug wrench to remove the gas plug:

Unscrew the gas plug and gas block retainer:

Remove the gas block:

And the front handguard:

Then, I got to work. The key was to take it slow and steady and not oversand the handguard. Instead, I sanded a little, then checked fit, then sanded some more.

The end result was a handguard that didn’t contact the operating rod unless I cranked it over counterclockwise, which should be perfectly fine for the kind of range shooting I’ll be doing with this gun. If I need to, I can always remove move material for an even more generous fit.

It’s also important to make sure that neither the stock nor rear handguard contact the operating rod. In the case of my rifle, only minor cleaning up was necessary to ensure proper function.

For best accuracy, I relieved my stock under the rear receiver enough that a sheet of paper would slip between. Supposedly, this helps improve the consistency of the receiver and stock flex during recoil. Tinydata also mentions in his guide relief cutting the rear of the stock for the firing pin. Both of these modifications are visible in the photo below:

The light area between the forward receiver cut and the toe of the stock is where I relieved the stock. Some folks have made this modification with a sharp step between the relieved and original areas, however I wanted my stock to have a more unmodified look, so instead I blended the transition. You can see the relief made at the rear right of the stock for the firing pin; I did this with my everyday carry Victorinox knife and it came out fine.

The last modification I made was to relieve the wood around the trigger guard housing. Tinydata advised that the rear of the magazine body should not touch the gunstock, so I relieved wood until there was no contact. The rear of the trigger guard body also should not touch the inletting of the wood, and the wood underneath the trigger ideally should be relieved enough so that the trigger does not make contact with the stock when pulled. While I was satisfied with the relief cutting I did there, test-firing the gun afterward showed that the trigger guard still was making contact with the stock.

The first range trip with the rifle post-modification showed promise, but the full potential of the rifle in terms of accuracy will only be realized with better ammunition (I used Greek HXP to shoot the group below) and more work:

My first 8-shot group at 30 yards, post-modification. Not a great group, but it’s a start. The shot to the left was called when I fired it. Excluding it, this is about a 3 MOA group, which is more or less what I’d expect with surplus ammunition and a mixmaster CMP M1.

A surplus M1 firing surplus ammunition cannot be expected to be a match-accurate rifle, but the M1 Garand is one of the most enjoyable military surplus .30 cal full-power rifles out there to shoot. Recoil has the same magnitude as other rifles in its class, but the recoil feels more on the “push” side than the “shove” side of the spectrum. And of course, for the range, the sights and trigger are excellent by surplus standards. All in all, a surplus M1 with a little tuning makes for a fantastic range toy.

Next time, we’ll talk about refinishing the new CMP stocks to give a more historical look!

Your Privacy Choices

Your Privacy Choices