This article on TFB will be the first in a number of articles I’ll be completing about the Russian AKS74U, to include an upcoming TFBTV episode about the carbine. Essentially I want to fill a void in research about the AKS74U, that isn’t there in our community, beginning with not only the nickname that we have given to it in the States, but really a name that has caught on for any folding stock SBR or pistol AK platform.

So to start off with the name “Krinkov”, where does it come from and how have we gotten to it. There are a number of theories about it, some more true than others, but we’ll examine each one, and I will provide what I have come up with so far.

The first theory is that it is Russian. At face value, this could seem true, by simply hearing the word “Krinkov” to a non Russian speaker, it might sound Russian. However, this is by far, not the case at all. Tim from Military Arms Channel has an excellent dialogue on this, explaining that the Russians have an entirely different nickname. I’ll take an excerpt from Maxim Popenkers site, World Guns:

Since its introduction the AKS-74U, unofficially known as a “Ksyukha” (variation of a Russian woman name) or “okurok” (cigarette stub)

In addition from Max’s book Assault Rifles, we have this entry:

Since its introduction the AKS-74U, unofficially known as a “Kysusha” (a variation of a Russian female Ksenia), “Suka” (bitch), “Suchok” (small tree branch) or “Okurok” (cigarette stub)

And this is Tim, explaining some of that from the Russian side.

Tim is correct in his explanation of what Russians would call it, but the biggest problem I have with his explanation is that he completely dismisses the role of the Afghan Mujahaden, saying that it is a “nonsense word”. In addition he speculates that maybe the first AKS74U taken off a Russian who was named Krinkov. The theory doesn’t hold any weight because for one, Krinkov isn’t a Russian name or in any sort of Russian vocabulary. Also, the fact that Pashtun speaking Mujahideen could speak or even read Russian is very, very rare, many of them being illiterate in their own language of Pashtu (illiteracy is an extremely large problem even in current day Afghanistan/Peshawar, and was much more so in the early 1980s). Furthermore, the circumstances of the Mujahideen capturing weapons from the Russians involved very little live prisoners. We’ll get into this in a bit as well, but for the overwhelming majority of time, the AKS74U was issued to helicopter and armored vehicle crew members. Contrary to popular belief, the amount of Russians captured in Afghanistan during the war, and the amount of Russians fleeing to the Mujahideen side was extremely low as well. Most of the time, the only way Mujahideen could get their hands on Soviet equipment was through disabled vehicles wherein the Russian occupants would already be dead, or through the corrupt selling of Russian arms to the Mujahideen by either Russians themselves, or Afghan government troops.

Most of the Mujahideen and Pashtun speakers that would have contributed to the name “Krinkov” would have been near Peshawar, and in the eastern regions of Afghanistan.

The second theory is much more recent, but it originates from a gun shop in Naples, Florida. The shop was called “Krinks” and was run by a certain Paul Mahoney, who being in the early 1990s was one of the first AK builders in the States to really take advantage of deactivated AKS74U kits, and put them together. The quality of them left much to be desired, but the fact of the matter is that the first mass producer of “Krink” kits in the United States was this guy Paul Mahoney with his gunshop “Krinks”. This might have certainly been one of the reasons why the name started to gain in popularity in the States, but it doesn’t help us at all in the actual etymology of the name.

My problem in the whole name origin is that we constantly see this theme of loosely attributing it to the Mujahideen, but yet there hasn’t been a single effort to get right to the source and really examine how that name might have even come about. Maybe it is ethnocentrism, maybe it is on account of laziness, maybe it is just accepting the status quo and not moving on. Either way, I’m going to present evidence that points to that fact that the name is actually a Pashtu word that has entered into our vocabulary, and is a testament to a twist in linguistics in the Pashtu language.

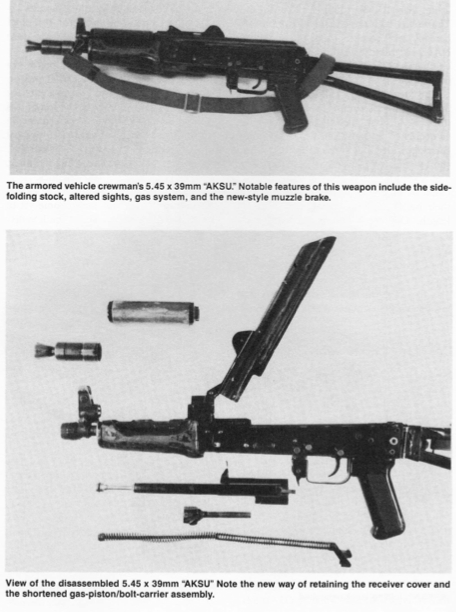

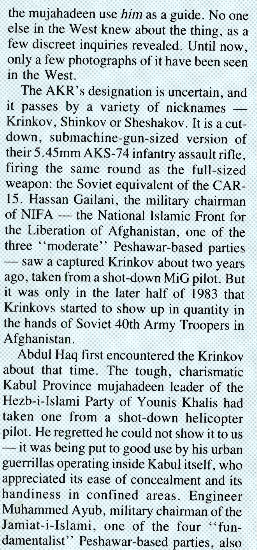

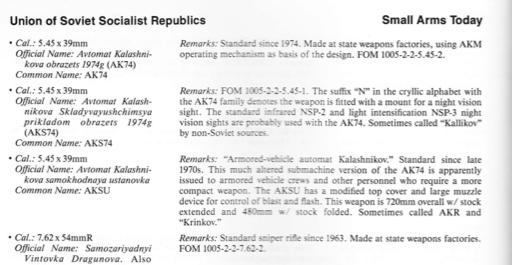

To begin with, we have to examine how the existence of this carbine became known about in the United States. I’ve often heard the claim that Soldier of Fortune magazine was the first entity to bring knowledge about the AKS74U, and even the AK74 to the West. I think this claim is more of a support for Soldier of Fortune’s reputation than any actual truth. Because just by looking at the facts, the famous Soldier of Fortune article that was run about the AK74 was in 1982, and the article about the AKS74U was in the July 1984 edition of the magazine. Looking at Jane’s Infantry Weapons from that era, and before, we see entries for the AKS74U, Sometimes labeling it as an AKSU 74, an AKSU and also as an “AKR”. This name most likely originates from Ian V. Hogg, as he was tied in with various intelligence circles at the time, that somehow came up with AKR. We still see this name in 1989, with Edward Ezell’s book, Small Arms Today.

Above is from Small Arms Today, and below is from “The AK47 Story“, both by the late Edward Ezell. Above he refers to it as the AKR/Krinkov, and below the “AKSU”. Both published in the late 1980s

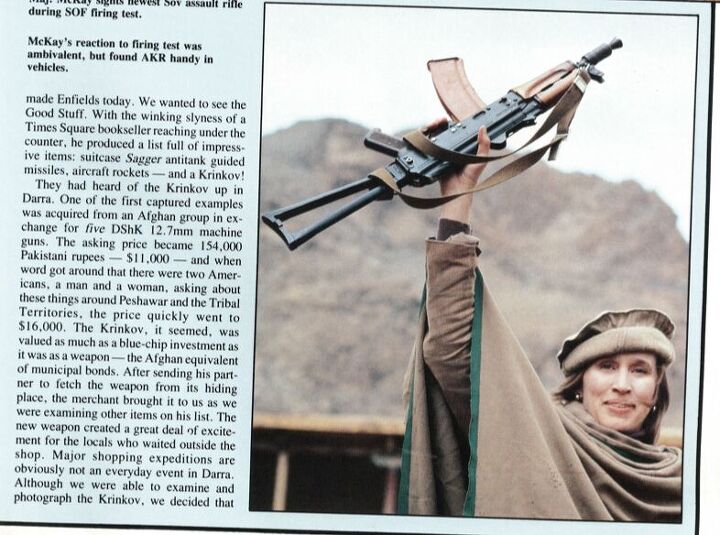

But going on to who actually deserves the credit of “discovering” the AkS74U, we have a sentence from the July 1984 edition of Soldier of Fortune, in which David Isby does an entire article about reviewing this new carbine, while he and an American Army Major are in Pakistan. He claims that initial knowledge of the carbine is from Ian Hogg, who in turn heard about it from a certain Peter Jouvenal. This guy was a video journalist, who has been in and out of Afghanistan since the late 1970s, and is extremely important because he captured one of the only video shots of Taliban leader Mullah Omar in person.

Below is the text from the Soldier of Fortune article detailing the origins and name of the AKS74U.

Peter Jouvenal, right, with Osama bin Laden. Probably the actual “discoverer” of the AKS74U in the West.

Within the Soldier of Fortune article, David Isby takes the name from the Afghans he was with. However he mentions two other names “Shrinkov” and “Shesakov”. These two names are also important, but because of the linguistics involved, I’ll get to that in a second.

As mentioned earlier, the difference between this article, and any other article on the internet, is that I’m going to the actual source of the name, which is from the Pashtu speaking peoples of eastern Afghanistan, and Pakistan. The name is not a “nonsense” word, it is a Pashtun word. I’ll start this off by showing a clip from a movie called Son of a Lion. Quite an interesting movie, it was made by an Australian EMT on his own dime, after 9/11, going to Peshawar and filming a storyline about a young boy who works in the arms trade but really wants to go to school to become educated. The culture and language displayed in the movie are phenomenal, but from a firearms perspective, it gives us an in-depth look at the arms trade in Peshawar. Apart from a few actors, the rest of the movie is completely shot amid the markets and daily life of the North West Frontier Province of Pakistan. There aren’t any “props” or staged settings. The locations are real, and so are the small arms portrayed. But in it, we have this once scene where the main character takes a “Krinkov” out to a customer to test fire it. He also mentions the connection with Osama bin Laden.

Now, to understand why the reference to Osama bin Laden was even mentioned, we have to understand a little behind why the AKS74U became prominent among first the Mujahaden, and then today among families of status. As mentioned previously, the weapon was only ever issued out to crew members of helicopters and armored vehicles. Contrary to popular belief, this wasn’t a favorite of the Spetsnaz at all, although it originally started out as a proof of concept for Soviet Special Forces. It was quickly ditched for the AKS74 because the longer barrel proved to be better in the vast distances that the Spetsnaz found themselves operating in. This from an interview that I conducted with Marco Vorobiev, a Spetsnaz Veteran of the Afghan war.

Miles Vining- I noticed in some of your talks that you don’t have much love for the AKS74U?

Marco- Well its alot of fun. Lets talk about it from a far away point here. The gun is a tool in a toolbox to complete a certain job. And the job could be a regular contact fight, lets say 500-400 meters, to include maybe clearing houses or compounds. So from that regard you want something small, maybe be able to use it in close quarter combat, something really, easy to handle, easy to maintain. Well that is fine, considering if you are a police officer going through a house. It shoots 5.45 as well, so thats good for wounding. On the other hand, as a carbine, you need to be able to hit targets out to 300 meters. You can do that with an AKS74, no problem, even with an M4. But the AKSU? You might if you spray half a magazine in that particular direction. But I even have one, I shoot it for fun, I get a big old smile on my face. It’s fun to shoot, it’s just like rrrrrrrrrrp, almost like a little toy so to speak. Mikal Kalshanikov himself told me that he loved it, although he was a very anti 5.45 guy, but he was a big fan of the AKSU for some reason. But you put yourself in an actual gunfight, with people screaming everywhere, trying to get comm up, you taste the metal of adrenaline in your mouth, and now you are trying to pick out targets in the distance… it’s really hard with that gun. We were always trying to get rid of it for the AKS74.

Thus, the weapon was strictly for crew members. And if we look at the context of the Soviet Afghan War, the biggest hinderances for the Mujahideen, were the Hind attack helicopters, and the BMPs. In fact if you look through Soviet photographs of the war, there is much evidence to attest to this, with helicopter crews even having thigh holsters carrying their AKS74Us. Thus, taking one of these monsters out of the fight would be one enormous victory for a small band of fighters, but more importantly, PROVING that you took one down would show everyone how brave or good you were. And what better way to prove it than to take a weapon that only these troops would have on them, an AKS74U? It not only proves that you were competent, but it also gives you something to defend yourself with. Even in the Soldier of Fortune article, we see just how rare and sought after these things were, even rising in price after word was passed around that an American was looking for one in Peshawar.

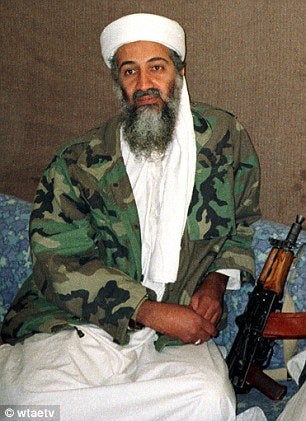

Now, Osama bin Laden claimed back to his Yemeni and Saudi buddies back home that he fought in the Soviet Afghan War. But the actual truth of the matter is that he probably was never near any of the fighting, most likely staying in a rear echelon capacity, directing funds and supplies to the front (if he even did that). But, on his return to the area in the mid 1990s, we have a multitude of pictures of him, with an AKS74U by his side in the camera frame. This was very deliberate, to the point of the gun sellers in Peshawar even telling the customer that “This is the Osama gun”. Although Osama never took down a Soviet armored vehicle or Hind, the fact that he was carrying the carbine showed a status symbol, and he was able to identify much more easily with local Pashtuns who didn’t understand his Saudi background, but absolutely understood his choice of weapon.

Somewhat off track, but this is important to understand how the name came to be, because even today, the AKS74U occupies a very lofty position as a status symbol in eastern Afghanistan, and Peshawar. Now for the real point of this article, below is a video I made with a close friend of mine in the United States, in which we discuss the term.

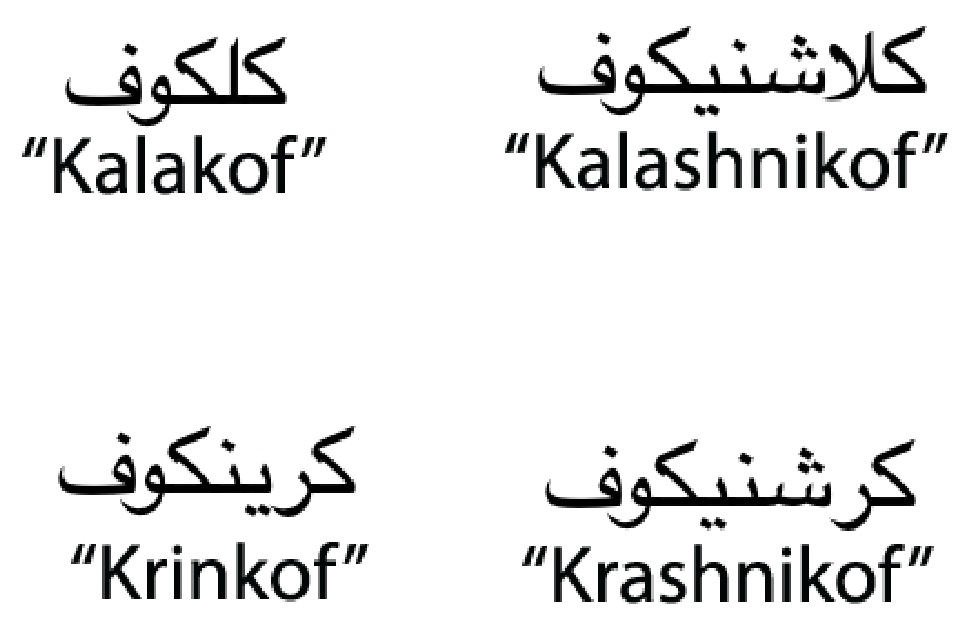

My friend mentions two names for the carbine in the video, the first one which is popular in Jalabad, is “Kalakov” and the second one is “Krinkov”. If you hear somewhat of an “F” sound at the end of the word, that is because there isn’t any “V” consonant in Pashtu, speakers instead using an “F” or a “W” sound to simulate a “V”. Now, remember what David Isby said the other names for the carbine were? “Shrinkov” and “Shesakov”? Using a little knowledge of the Pashtu language, the names pair up to be the same word. There are two dialects of Pashtu, the southern, or Kandahari, and the eastern, or the Nangahari. So looking at this words, “Krinkov” and “Shrinkov” are actually the same word, just pronounced differently, while “Kalakov” and “Shesakov” are a little more different, but dropping the “la” sound, the words are also the same.

From the full form of the word on the right, going into the nickname for the AKS74U on the left, the differences between the top and bottom are in different Pashtu areas of speaking.

But how exactly did these words come about? As my friend mentioned, adding an “ov” to any word makes it Russian-ized in Pashtu. So that explains the last part of the word, and the first part is probably a bit of vocabulary added on, to signify the importance of the AKS74U as a status symbol. Because it isn’t just any old “Kalashnikov”, its a “Krinkov”, and you know I got it from that Hind I blew out of the sky a week ago. Another tidbit that my friend brought up after the camera was off, is that for some reason, in Jalabad, the Pashtuns refers to the Kalashnikov rifle as that, a “Kalashnikof”. However, in other parts of eastern Afghanistan, the same name is actually pronounced “Krashnikof”. And this might actually be the truest jump to “Krinkof”, as going from “Kalashnikof” to “Kalakof” is very similar, as is going from “Krashnikof” to “Krinkof”. In both cases, the “L” in the first one, and the “R” sound in the second one are maintained in their nickname for the short rifle.

I hope this was an informative article, and was able to really get to the point of “Why do we call it this?”. If anything, the most important part of all of this, is that the word isn’t a made up, nonsense word, but instead has very important historical and cultural attributes, and an etymology that comes from a defining moment in history. There is much evidence to point to the fact that Afghanistan might just have been the straw that broke the Soviet Unions back, and this word directly came out of that struggle. In addition, it is a Pashtun invention, and is still very much alive and well in eastern Afghanistan and Peshawar.

Your Privacy Choices

Your Privacy Choices