The Editor writes: This article was written by Adventurer on his experience of using firearms in the extreme cold. The scenario that necessitated this was an expedition undertaken by three friends to ski across the Arctic island of Svalbard.

The northern tip of Svalbard lies around 600 miles from the North Pole. The island is prone to extreme weather and is home to a large population of polar bears. The main settlement of Longyearbyen has a population of around a thousand people. Due to the threat from bears it is mandatory for anyone traveling outside of the settlement to carry a suitable firearm.

For protection our team took three weapons: A Mossberg 590 with ghost-ring sights and loaded with solid slugs. A Kar 98K that was a relic of the Nazi occupation and still carried the swastika & eagle stamped on the breech and a flare gun that was loaded with “flashbang” cartridges which would explode a few seconds after firing. The idea behind the flare gun was to be able to scare a bear away from us before having to use either of the other weapons.

Although my memory may be playing me false I have a vague notion that the Kar 98K had been re-barrelled to accept .30-06 ammunition. More learned readers may wish to debate this but in practice I doubt if there would be much difference in the effectiveness of .30-06 over 7.92 for stopping polar bears at close range.

The eagle & swastika on our rifle. The Kar 98K was a pleasure to carry and probably ideal for this purpose, however like all weapons, its effectiveness is dependent on the individual.

Reloads for the shotgun were carried in a pouch that was secured to the belt of the shotgunner’s sledge harness. The design allowed the pouch to fall open once the user unclipped a fastex buckle, revealing several rows of cartridges secured by elastic straps. The pouch was supplied by a sponsor who specialised in manufacturing uniforms and accessories for military/law enforcement. In practice we found that snow & ice would get inside the buckle to freeze it solid and render the pouch useless.

The flare gun came in a holster that held three cartridges and was slung via a strap over the shoulder to hang at waist height. Both this and the rifle were rented from a shop on the island that specializes in outfitting expeditions to the interior of the island.

Flare pistol – type unknown. Loaded with “flashbang” cartridges this was intended to scare away the bears before it became necessary to use the other weapons.

The rifle came with a leather sling and for the shotgun we secured from a Swedish sponsor (Neverlost) a padded sling that was made in dayglow orange. The idea being that it would aid identification and retrieval of the weapon in a high-stress situation.

We also carried a contraption known as a “Snubblebluss”. This was composed of a trip-wire that we’d erect around our tent at nights. At each of the four corners was a small flare mounted on a stake that would be set off if a bear decided to come into our camp.

A camp at night up on the glacier, at that time of year and that far north there is practically 24 hours of daylight, on the final day of the trip we saw the sun set for the last time that year. Note one of the tripwire poles on the right hand side.

“Snubblebluss warheads” attached to spare ski poles, if I recall correctly the little polar bear heads were on the safety pin that “armed” the charge once the trip wire was attached.

Before leaving we all familiarised ourselves with every weapon and each fired a few rounds to test the actions. Even running through some bear “drills” and rehearsing several scenarios and the rules of engagement that would govern our actions. We also cleaned the weapons thoroughly and removed all excess oil. Although I have never seen it for myself I have heard that even oil can freeze in very low temperatures. I believe that special lubricants can be obtained that have a lower freezing temperature but I hadn’t gone out of my way to source any as I thought their use was probably more appropriate to automatic weapons that could gather excess carbon deposits from extended firing under combat conditions.

The phenomenon of having and using firearms in the Arctic is that they will gather condensation if brought into the warmth. Just like the condensation that forms on the outside of a cold beer when it is taken out of the fridge. Once the temperature in your shelter drops again after the cooking stove goes out (or wood stove if you are lucky enough to be in a cabin) then the moisture that has condensed onto the metal surfaces and possibly inside the action of your weapon will re-freeze. Over consecutive nights this can lead to a build-up of ice which could jam the action.

We’d learned that NATO doctrine in the Arctic is for troops to build a small “weapon rack” out of branches to leave their weapons upright and off the snow outside a tent or shelter so as to avoid this phenomenon. However troop formations will always have a sentry, who it is hoped can keep watch and give warning of any approaching enemy, giving the sleeping soldiers’ time to retrieve their weapons.

Perhaps naively we decided not to keep a bear sentry at nights, after hauling 130 lbs sledges for 20-30 miles each day over glaciers and passes perhaps you can understand why.

Instead we chose an interim measure. When we pitched camp and lit our cooking stoves to melt snow for drinking and rehydrating our freeze-dried rations, we would leave the weapons outside. Once the temp had dropped again, we’d bring the weapons into the “ends” of the tent, between the two layers of fabric so that they’d be handier in an emergency and out of the snow that could still get into their working parts and potentially jam the action. The tent had an exit at both ends and we would keep one weapon next to each door.

The effect of “spindrift” during an Arctic blizzard has to be seen to be believed. Tiny particles of snow driven by the high winds can force themselves into the smallest of spaces and gather there. After one such blizzard I opened a pocket that had been zipped shut to find it full of fine snow. The snow had actually been driven in between the teeth of the zip to gather there over several hours. Leaving a weapon exposed to “spindrift” under such conditions could easily lead to the spaces between parts becoming jammed with fine snow and inoperable. When weather allowed, we would regularly check the actions and magazines of our weapons to ensure that they weren’t becoming clogged with snow or ice.

During the day while we were skiing and dragging our sledges, we carried all weapons slung so that they could be brought to bear at short notice. Initially we rotated who would carry what each day, but after a week we decided that we’d stick to the same weapon so that each of us would become more familiar with our particular firearm and hence more likely to use it effectively if the need arose.

I settled on the rifle and would carry it slung diagonally across my back with the butt down on the right side. I discovered that the Kar 98K is a beautifully balanced weapon and with practice it can be swung into the shoulder from this slung position in one fluid motion.

I did experiment carrying the rifle slung with the butt up over my right shoulder, thinking that I could draw it over my head with the right hand by reaching back over my shoulder. But I found that this was totally impractical.

Experimenting with carrying the Kar 98K in different styles. This one was not very practical. Note the snow that has become trapped in the heat cover of the Mossberg 590

Over time we discovered that snow would enter the open muzzle of our weapons and adapted covers from zinc oxide tape we’d brought to bind the blisters on our feet.

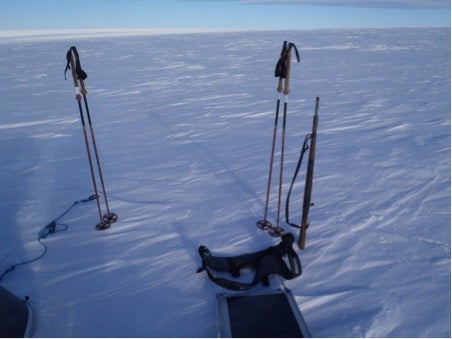

Initially when stopping for a break and some water from our thermos flasks I’d make a little stand for my rifle from ski poles. By linking them together in a tripod with the straps of the poles around the barrel it was possible to lean it against them so that it would stand upright and stay out of the snow. Later on I discovered that by simply smashing the butt of the rifle into the snow it would hold it upright while you could go and sit on your sledge for five minutes to enjoy some chocolate and a cigarette. This method was not possible with the Mossberg as the inertia of smashing the butt into the snow could partially “rack” the slide.

The easiest method of resting the rifle on stops.

At one point when we were just 12 miles shy of the north tip of the island we cached our heavy sledges and made a dash to get there and back with just light packs and weapons. Owing to the need for speed we found that it was best to carry our long-arms strapped to our packs rather than slung as before.

Although we saw plenty of bear tracks in the snow we only saw a bear on one occasion. It was a mother and two cubs that were moving away from us as we skied along the side of a frozen fjord. She was leading them up into the hills above us (presumably to get away) and was never any closer than 200 yards. The quality of the images we got were so poor that there is little point in reproducing them here.

Wherever possible we camped up on the glaciers and away from the sea ice. The bears are more likely to be found near sea ice because their primary source of food is the seals that come up through this ice through holes that they maintain. The bears typically hunt by waiting beside one of these holes to catch the seal as it comes up for air.

Despite never having to use the rifle in self-defence I can say with some justification that it saved my life. On one occasion we were skiing down a glacier to get off the high ground before a major storm was due to hit the island. Expediency had led us to choose this route in preference to a safer one. Once we reached the snout of the glacier we discovered that our progress was impeded by numerous crevasses that blocked our path.

I am ashamed to say that I stupidly left my gear and my friends to try and scout ahead for a way through. Walking without skis, climbing harness or being roped up to any of the others I fell into a narrow crevasse that was concealed by a thin crust of snow over the top. What saved me from falling any further was the rifle jamming against the lips of the crevasse and the sling under my right armpit arresting my fall. This gave me the chance to reach up and drag myself out.

Although I can’t speak for the effectiveness of the weapons we chose since we never had to use them I do know that similar weapons have been successful in stopping attacking bears in the past. One notable exception being the incident in 2011 which was covered by TFB here:

Apparently, while under considerable stress the “shooter” forgot to remove the safety on his rifle and cycled several rounds through the chamber while being unable to fire any of them. The same rifle was eventually recovered and an ejected round was re-chambered and used to shoot the bear dead after it had killed one and mauled two others.

The coroner’s verdict was that the safety had been on, however I’d be curious to know from anyone familiar with the trigger/firing pin mechanism of this weapon if a similar effect could have been produced by snow or ice inside the action. The rifle was a Kar 98K identical to the one I carried.

This happened about a year after our expedition.

Residents of Svalbard commonly use pump action shotguns, bolt action rifles in .308 & above and a variety of large calibre revolvers, I think the largest I saw was .500 S&W, although I believe .460 was more common. I saw one individual with a particularly nice looking Lee-Enfield carbine in a black nylon stock.

I’m sure much space below will be devoted to proposing the ideal calibre/platform combination for defence against polar bears and I’m sure I could think of a few myself that would work better – if you were to step straight out of a warm, pleasant, domestic environment and into a bear encounter.

However if the user is being exposed to the weather for months on end, freezing temperatures, spindrift, blizzards, falling over in the snow, falling on the weapon, being exhausted, having it dragged underneath you by a runaway sledge on a steep slope or being otherwise used and abused. Then I really can’t think of a better platform than the Kar 98K or indeed any other of the main WWII era bolt action rifles.

Although a pistol might be lighter and handier, I know I’d have greater confidence in my ability to line up the sights of a rifle on an incoming target in a high-stress situation. But perhaps that’s because I have more experience with the latter – others with more experience behind a pistol might disagree.

Lastly, I find it especially cool that in an age where equipment is being honed to near ridiculous levels of perfection in terms of space-age materials, metallurgy, and tacticool accessories (relevant though they may be in certain situations) – the WWII era bolt action still has a valid place in a practical life-saving application.

I look forward to hearing from others with different perspectives and experiences. To my mind the best debates are ones where I’m forced to change my opinion on a subject – because someone better informed has successfully challenged my beliefs and expanded my knowledge.

Your Privacy Choices

Your Privacy Choices