As we wind down this week, putting behind us all the tactical gadgets, fine craftsmanship, and cutting edge technology of the 2015 SHOT Show, I thought it would be good to take a detour to look at something… A bit different. Sometimes it’s easy to put on the ol’ blinders, focus in on a topic, and forget that there’s a whole wide world of fantastic, bizarre, anachronistic, and sometimes downright dangerous firearms out there.

Today we’ll be looking at a kind of weapon that, despite its primitive nature, is still being built and used in the Central Asian frontier today. In the wilderness, where metallic cartridges and even percussion caps are few and far between, but where blocks of lead and flints are available, there still is a need for a simple, effective, and most of all maintainable weapon that can be used to take game or defend oneself. This weapon is the snaplock, and today we’ll be looking at a Mongolian carbine variation, from Ölgii, in western Mongolia.

This weapon is owned by Stephen Bodio, author, falconer, and world-traveller; many thanks to him for letting me take a look at it!

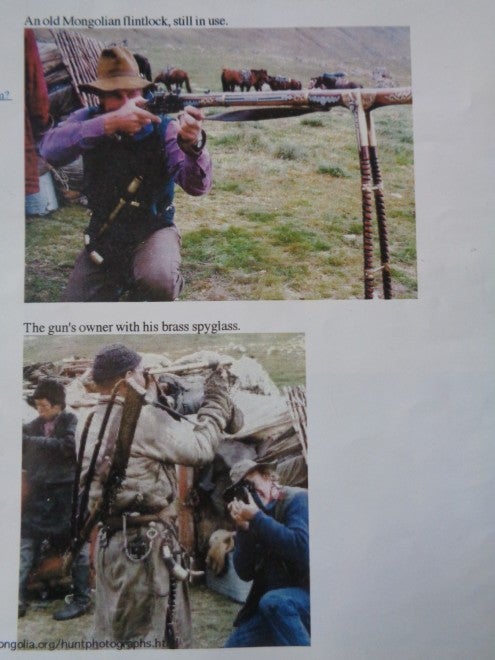

The rifle was probably made in the 1950s, though it most likely recycled components (especially the barrel) from older weapons. In Central Asia, where these kinds of flint-primed weapons are common (indeed, until recently they were dominant, as cartridge-firing weapons and their ammunition had not so widely proliferated on the frontier), the most widespread variation is a long, heavy rifle, weighing between twelve and fifteen pounds, which is fired atop a sharpened shooting stick (“sazhanki”) or a bipod made from, or to resemble saiga horns. This weapon is unusual – it is a short carbine, less than three feet long, with a stock that appears to be made from a simple wood plank. To their users, these snaplocks are only called “guns”; there is no special name for the type.

Top: A more traditional “long rifle” flintlock variation, with external lock, atop a bipod of wood, shaped like saiga horns. Image source: Stephen Bodio.

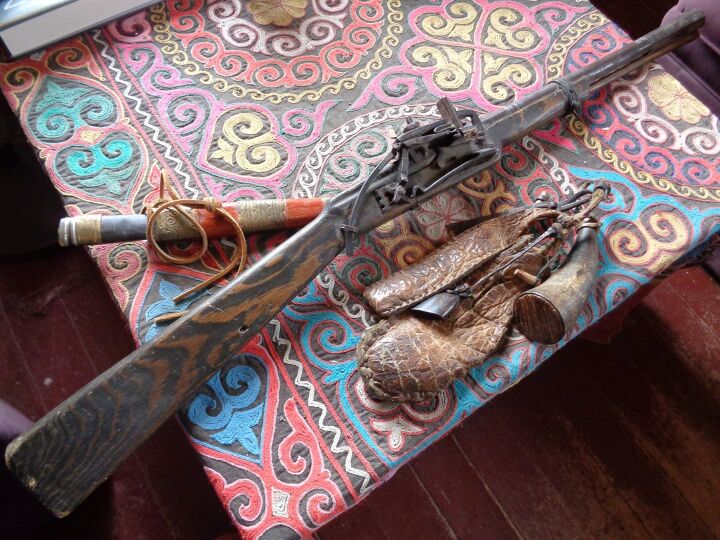

The lock lacks a frizzen or any sort of pan cover, and the entire mechanism is external, making the weapon a snaplock – a pattern of flint-primed gun that predates either the flintlock or snaphaunce. In practice, the pan would have been protected from the elements by a felt pad. The steel, as the rest of the lock, is totally rudimentary, and appears to be made from scrap by a village blacksmith, as indeed it probably was.

Betraying the weapon as anything but ancient, the barrel and lock are held to the stock by a modern looking hex bolt and nut:

The barrel itself, in contrast, looks antique and is much more ornate than the rest of the firearm. Despite the overall crudity of the weapon, the barrel is rifled:

The “two-quarters” octagonal, decorated, leather-banded barrel clashes with the apocalypse chic of the rest of the firearm:

Firing the snaplock was a little out of the question – however, I was able to dry-fire the gun, which most closely reminded me of another Eastern firearm – the PPS-43 submachine gun. The delay between releasing the flint and it making contact with the steel was palpable, and more than a little concerning:

What the carbine has for sights resemble those on a GI-pattern 1911 – crude and small, but workable:

The indexing mark of for the barrel and tang can be seen in this view of the carbine. Given the nature of the weapon, such a mark seems like a pretty frivolous addition.

In Central Asian villages, even blacksmiths are uncommon, which means field-expedient repairs are common, and many percussion weapons get converted to the easier-to-maintain flintlock ignition. Purpose-built guns like these would be purchased by shops on rare trips to larger towns. The quality of the weapons would typically be fairly uneven, so patrons would not be allowed to fire the guns before buying, lest the shop be left with a bunch of undesirable junk guns. As a result, interesting superstitions about how to tell the quality of a rifle came to be, including putting a steel pin in a puddle of saliva on the barrel, and slowly rotating the barrel. By watching the rotation of the pin in the saliva, supposedly they could tell which barrels were good.

Like all muzzle-loading guns, the weapon simply wouldn’t be complete without its “kit”, which includes a powder horn, scraper, bullet starter, lead pouch, bullet mold, and powder measure:

To us in America, where even in remote regions the UPS truck comes every Wednesday, a weapon like this goes beyond “quaint” and straight into being “downright primitive”. However, for a hunter in remote Central Asia, this gun may be all he can afford or maintain, and indeed, some like it that way:

Our fathers and grandfathers did not know caplock guns, but they shot more game than we ever could; thus, it would not be appropriate to acquire what we are not accustomed to, and what we are not good enough for.

–Notes of An East Siberian Hunter, by A. A. Cherkassov, translated by Vladimir Beregovoy and Stephen Bodio.

Your Privacy Choices

Your Privacy Choices