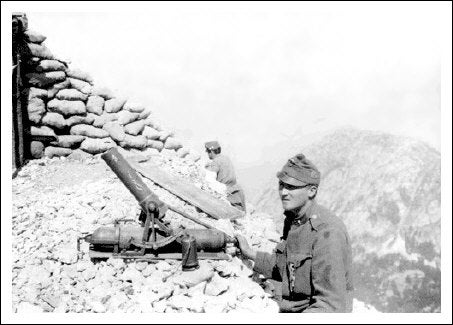

trench warfare on the top of the alps

The Isonzo front between Italy and Austria-Hungary in World War I was a battlefield of extremes. Fought amongst the Alps, rockslides, avalanches and frostbite were just as deadly as the bullets and shells. One difficulty that the units that fought there faced was the employment of light artillery, infantry guns, and mortars in the extreme mountain environment. This author has personally been to these areas (now in Italy). The fact that armies battled on top of and sometimes assaulted up such stupefying heights is mind-blowing. Seeing such terrain in person really drove home how difficult their tasks were, and how extreme the environment was in which they fought. When visiting some of the fortifications and battlefields in the area, this author was first exposed to the little-known weapons system covered in this article.

some of my personal photos of an exhibit in Austria noting the use of these weapons

At times, firing trench mortars or mountain guns by units fighting in this terrain could potentially bring an avalanche down on their own position. Another risk of using traditional artillery was that the smoke, flash, and noise of the guns could give away their position quite easily across the clear air of the treeless mountain peaks. In 1915, Austrian troops of the 58th infantry division started coming up with their own solution to this problem: the pneumatic trench mortar, or Pressluft-Minenwerfer (Also called Luftminenwerfer).

The Design of “airgun Artillery”

Early pneumatic mortars of WWI, including the 8cm models made in at a field workshop of the 58th Infantry Division, used a breakable “fuse screw” attached to the mortar bomb. The bomb was loaded via the muzzle, and the fuse screw attached to the bomb and a plate in the chamber. The breach of the mortar was then closed, and pressure from a pre-charged cylinder was let through a hose into the breach. When pressure built up enough, the screw would snap and away the projectile would fly, up to a distance of 1000 meters. A 15cm model was later developed for further explosive power on target. Both models were much quieter than the conventional mortars or mountain guns, and provided corresponding tactical advantages.

The 8cm mortar developed by the 58th infantry division. Reports from the field indicated that it was very quiet. (Photo credit: Museo Storico Italiano della Guerra)

Projectiles were first made in small-scale at the field workshops and then later at the “Österreich Metall Werke” in Brno. Cyclinders could be recharged at transportable air compressors, which had either steam or gas engines. They were the size of the small trucks of the time. Cylinders and ammunition would then be transported to front-line units via mules, or in some places rope and pulley systems that went straight up vertical faces from the valley floor. While there was the extra hassle of transporting the cylinders back and forth, the mortars were quiet, did not bring undue attention or avalanches down on the firing position, and did not use up the valuable war material of propellant explosives.

12cm M16 Pressluft-minenwerfer ready for testing. Note the pressure gauge. (Photo credit: Wikimedia commons)

Pnuematic Mortar use on other fronts and further developments

Both the French and Germans also used pneumatic mortars. The German’s first use was in 1915 in the Vosges area, with the Ehrhardt & Sehmer 10.cm mortar. The French also first used pneumatic mortars in 1915, ranging from 50mm-120mm, with designs by Edgar Brandt. Accounts vary as to who copied who. Austria-Hungary remained the greatest user of the weapons system, with much interest in the concept by the Teschnisches und Administratives Militär-Komittee, or TMK. Though designs were manufactured to fire projectiles up to 20cm in size, the most successful (and most produced) model was the M16 12cm Pressluft-minenwefer. This design used a gripper which would grab onto a protrusion on the rear of the projectile after it was loaded in the muzzle. In early models, the mortar men would manually release the grippers when the appropriate pressure was reached. Later models had an automatic release that could be set for certain pressures, depending on the desired range.

German troops using a pneumatic mortar of Austrian design, most likely the 12cm M16 (photo credit: Wikimedia commons)

The pneumatic mortars’ true advantage lay in small-scale use in the alpine terrain of the Isonzo front. When they started being employed in a large scale by the Austro-Hungarian Army, two major disadvantages started to arise: Filling and transporting cylinders, especially for the larger mortars, became a major burden on the logistic system of artillery units. In addition, rubber for the seals on such systems was becoming scarce. Leather was tried as an alternative, but was somewhat unsafe to use for higher pressures and longer ranges. Eventually the air-powered mortars lost out to conventional designs in non-alpine warfare situations.

Hungarian troops of the Honved prepare to fire their pneumatic mortar

(Photo credit: Wikimedia commons)

Through the years to present day…

After researching this subject, this author is now somewhat bemused by press releases from airgun companies claiming to have the newest, heaviest caliber PCP air rifles. Pneumatic weapons of very heavy caliber have been in existence for over a hundred years, beginning with “dynamite guns” in the late 1800’s, pneumatic naval artillery used by Brazil in the early 1900’s, the mortars we have covered here, and the Holman Projectors used by the British in World War II. It certainly gives one something to think about next time one attends a “Punkin’ Chunkin'” competition this fall…

Primary Source Used:

Ortner, M. Christian. The Austro-Hungarian Artillery from 1867 to 1918: Technology, Organization and Tactics. Militaria, 2008.

Your Privacy Choices

Your Privacy Choices