In 1821, inventor Isaiah Jennings* of New York City, NY received a patent improvement on the earlier 1784 (!) multi-shot flintlock patent by Joseph Belton. I’ll illustrate below what is believed to be Jennings’ improvement.

Reuben Ellis of Albany, New York coordinated the manufacture of these rifles by R. & J.D. Johnson of Mildletown, CT, and the sale of these rifles to the State of New York where they were martially inspected.

According to Moeller’s American Military Shoulder Arms – Volume II, 521 of these flintlock repeating rifles were purchased by the New York State Commissary General in 1829 at a cost of approx. $25.21 each (or the very very rough equivalent of about $640 each in current dollars).

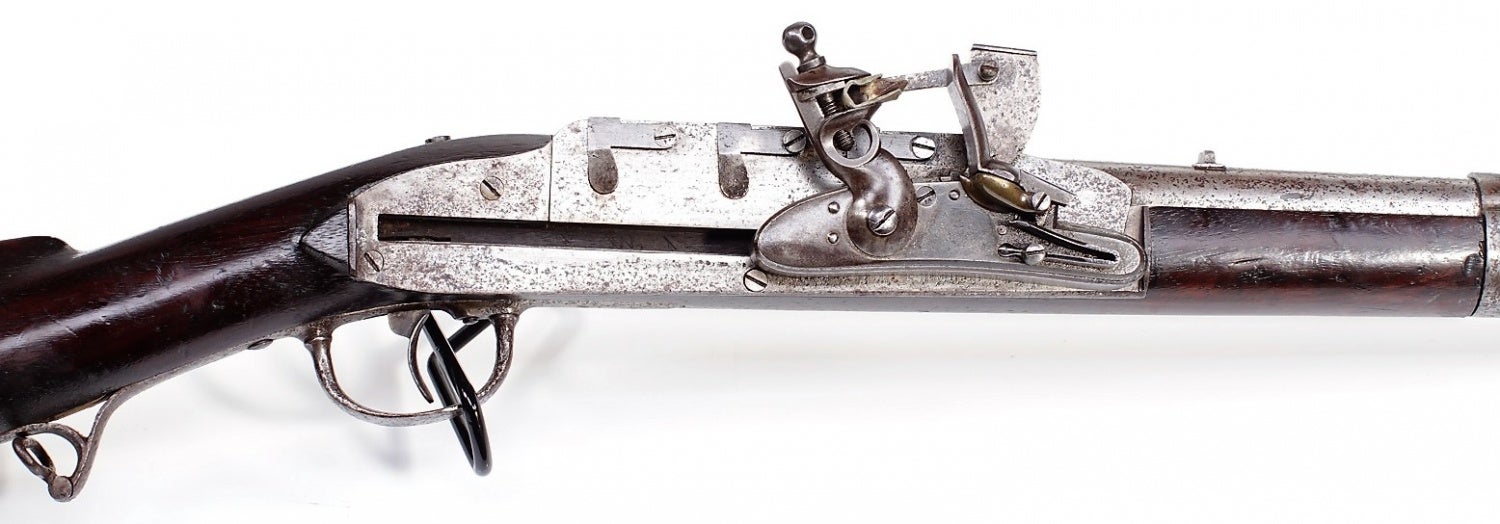

Action of the Ellis-Jennings Flintlock Rifle, in the loaded position – Institute of Military Technology collection

To load this rifle, powder and ball is inserted in the traditional manner and tamped firmly. Then a superposed load is inserted while the arm is still vertical, then another, and then another. (It is beyond my expertise to know if wadding would have been used. I suspect not, as the use of powder/wadding/ball or even powder/wadding/ball/wadding may give an undesirable overall length of charge – as well as contributing to potentially imprecise compactness of each.) Note: The rifle’s .54 caliber refers to the grooves, and would have used a .525″ ball – with a patch wrapped around the ball to take up the difference and engage the rifling.

Action of the Ellis-Jennings Flintlock Rifle, hammer and frizzen back – Institute of Military Technology collection

The important feature shown in this picture is that drawing the hammer back closes the frizzen, moves the hopper into the vertical position, and primes the flash pan. The hopper hold enough powder to fill four or more shots. Though the volume appears small, flintlock shooters are consistent in their advice not to overfill the flash pan. This mechanism is believed to be Mr. Jennings’ portion of the patent.

The trigger is then pulled, the hammer drops, and the frizzen is thrown forward.

Action of the Ellis-Jennings Flintlock Rifle, second shot primed – Institute of Military Technology collection

This is where it starts to get a little complicated, but it will clear up quickly. The swivel cover for the subsequent touch hole is rotated up, and the sliding lock is slid backward. The hammer is once again drawn back, automatically closing the frizzen and charging the flash pan. Shown above is the previous touch hole with nothing to do.

Action of the Ellis-Jennings Flintlock Rifle, third shot primed – Institute of Military Technology collection

Here the first two swivel covers have been rotated out of the way and the lock slid back again.

Action of the Ellis-Jennings Flintlock Rifle, fourth shot primed – Institute of Military Technology collection

And finally, the fourth shot. At this point you’re probably wondering how the trigger is actuating the fall of the hammer.

Action of the Ellis-Jennings Flintlock Rifle, trigger forward – Institute of Military Technology collection

Here we see the trigger in the forward position and the trigger bar in the down position. Note also where the sliding lock engages the subsequent shot’s swivel cover/touch hole.

Action of the Ellis-Jennings Flintlock Rifle, trigger engaged – Institute of Military Technology collection

Here I have used the prop stand to engage the trigger and raise the trigger bar. The bar lifts up on the lock’s sear to release the hammer.

Action of the Ellis-Jennings Flintlock Rifle, touch hole – Institute of Military Technology collection

This last picture may be redundant, but attempts to show the receiver’s touch hole through the lock’s touch hole.

Worth noting is the fact that there was a nearly identical model in a ten-shot configuration, and a similar all brass pistol/carbine model in a twelve-shot configuration. Very few have survived, for what I would consider “obvious reasons”.

For much more on Isaiah Jennings, see this Scientific American article.

* Mr. Jennings’ first name is sometimes erroneously spelled Isiah.

Your Privacy Choices

Your Privacy Choices