Earlier this week, my fellow TFB writer Pete M wrote a post arguing that a manual safety has no place on the modern defensive handgun. I think he’s right for the most part, but I’d like to explore something he didn’t consider.

Pete’s point is well-made, I think, but he ignores the squishier elements that have changed since then and now, stuff of the sort ‘twixt people’s ears. Pete argues that manual safeties existed to prevent early automatic weapons from firing when dropped. Perhaps the insistence of manual safeties during the early 20th Century was less a problem of the firearms then not being drop safe, and more a matter of grey matter. We should ask: How did the military officers (especially), police (to a much more limited extent than now), and civilian shooters (almost nonexistent besides gentlemen carrying smallbores in their pockets and practicing with popguns in their parlors) think about the problem, what issues did they prioritize, and how did they train?

Indeed, far from being unsafe when dropped, the 1911 sports a grip safety which prevents just such an accident, regardless of the position of the manual safety lever. You can drop the pistol, chamber loaded, safety off, hammer cocked, on the ground all day long and it will not discharge. That is, until while handling it your finger snakes into the triggerguard and you cause an ND…

That brings us to a much more critical factor: Gun safety training back then was in its infancy. Patron Saint of Gun Safety Lt. Col. Cooper wouldn’t even be born for another decade; the invention of his Four Rules would wait for another half-century after that. A manual safety, then, essentially stood in for Rule 3.

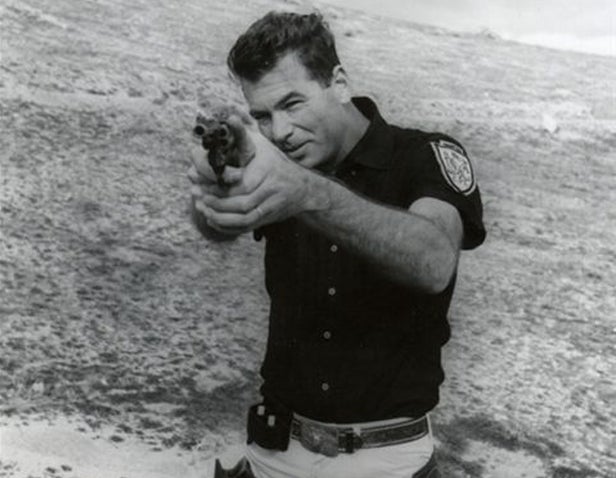

To add even more context, LA County Deputy Sheriff and pistolero Jack Weaver (who practically invented modern combat shooting) was eight years behind Cooper to walking this earth, and even the FBI crouch wouldn’t be developed for several more decades in 1910. The shooting forms of the day when the 1911 was being developed centered around a stance more akin to modern Bullseye competition than what we’d today consider practical shooting: Slow, deliberate, and – without using the support hand – demanding of a crisp, light trigger pull for maximum accuracy. Such a trigger, even today, begs for a manual safety, or at least a double-action/single-action set up.

So maybe it was less a case of the technology not having caught up to reality as it was the doctrine and training. The infancy of safety rules and training, and prevalence of what were already by then obsolete pistol shooting techniques meant that manual safeties were really essential for pistols in the early 20th Century.

We can see a similar case of this kind of doctrinal influence in an example from military service rifles. Consider the French MAS 36 rifle, a weapon of absolutely impeccable design for its class, but one that lacks (as Glocks do), any manual safety, or indeed even windage-adjustable sights. These features weren’t absent because of any technological advancement making adjustable sights and safeties obsolete, but due to the specific French doctrine at the time. For safety reasons, it was beaten (in many cases literally) into French soldiers that rifles would be carried with no round in the chamber; ergo a manual safety was superfluous and only added cost to a weapon being used in that context. Likewise, the French held that the individual had no business adjusting his rear sight, that was something done at the armorer level, and the lack of any windage adjustment ensured a soldier wouldn’t accidentally knock his sight from zero.

Going back to pistols, I am a member of the Glock collective (assimilate or die!); I abandoned several years ago my CZ-75 – an excellent handgun that I carried cocked and locked – in favor of the safety-less fantastic plastic. For me, the “working” handgun needs no safety; in fact, I find that I tend to be more respectful of (and therefore safer with) guns that have no “safety net” than those that do.

But it’s all a matter of context.

Your Privacy Choices

Your Privacy Choices