This post was written as a companion to an upcoming Gun Guy Radio podcast, hosted by Ryan Michad. The discussion below will be expanded upon in the show when it’s released later this month, but for now, read on to learn more about the past, present, and future of infantry weapon calibers!

1: What is caliber configuration?

Caliber configuration is a term used to describe the nature of small arms ammunition, the topic of this post dealing specifically with ammunition for infantry weapons. First, a definition is in order: Caliber configuration refers to the specific dimensional and ballistic characteristics of a cartridge, in the case of this post a military standard infantry weapon cartridge. 5.56x45mm NATO has a different configuration than 7.62x51mm NATO, which in turn has a different configuration than 9x19mm NATO. Each of these rounds serves their own purpose, although for the purposes of this article we will ignore pistol caliber configuration.

It is complex subject, with few easy answers, and is often erroneously reduced to a matter of ballistic “performance” without regard for actual real-world effectiveness and balance. The demands place on the infantry caliber pull in opposite directions: The ideal round kills instantly with one shot, has no recoil, weighs nothing, has a perfect laser-trajectory, no muzzle flash, costs nothing, takes up little or no space, creates a suppressing hurricane of air and loud sonic boom around the target, yet is silent at the muzzle, penetrates all barriers at all ranges with no loss of effectiveness (while still having limited penetration for use in training facilities), and has no maximum range (while still having a maximum range within normal Army training ranges). Obviously, many of these “ideal qualities” are in perfect opposition to one or more of the others, and in many cases it’s a challenge to even study a single performance metric well enough to characterize in such a way that its importance can be qualified enough to set a requirement. This is, for example, the case with suppression. Enemy forces clearly are suppressed by close small arms fire, but studies on which calibers suppress the best, and how to optimize a projectile to suppress the enemy have been mostly inconclusive. Therefore, there is a serious question about how suppression should be valued when designing a new infantry caliber, one that’s difficult, if not impossible, to answer currently.

Shown is the 8×63 Bofors on the left, and the 5.7x28mm on the right. Attributes of both rounds are desirable in infantry small arms rounds, but their great differences are obvious. Therefore, a balance must be struck.

2. A very brief history of military calibers

Beginning with the metallic cartridge revolution in the 1850s, military forces began adopting metallic cartridge-firing guns in the late 19th Century. While the benefits of the breechloading single-shot weapons that fired them were obvious, the metallic cartridges themselves brought both advantages and disadvantages. The metal shell holding the propellant and primer was much more resistant to the environment than previous paper cartridges, yet also added weight and bulk to the infantryman’s ammunition. While the first metallic cartridges were designed around the previous muzzleloading caliber paradigms, improvements were quickly made, chiefly by reducing the caliber. .58 caliber bullets gave way to .50 caliber, then .45, and eventually jacketed .30 caliber round-nosed bullets. Interestingly, these last projectiles, tough enough to withstand the violence of accelerating to muzzle velocities above 1,900 ft/s, severely compromised the shock effect of the rounds, although they greatly augmented the penetration. To counteract this problem, different exposed-lead bullets were invented, both field-expedient and production; the most lasting of these being the jacketed hollow point and jacketed soft point types, still in use in the civilian world today. These designs, however, were quickly deemed needlessly cruel in international law, and banned in warfare by the 1898 Hague Convention. From the turn of the 20th Century, the early ballistics science of the period made possible bullets shaped for supersonic flight. These bullets possessed higher muzzle velocities than ever before, with the often-copied Spitzgeschoss Patrone nearing 2,900 ft/s. These bullets complied with the provisions of the Hague, but due to their shape and high muzzle velocity performed very differently in tissue. Their rear-heavy conical shapes quickly destabilized, and their high energy and high muzzle velocity greatly improved effectiveness versus their round-nosed predecessors.

The 7.65x53mm Argentine on the left is typical of ~.30 caliber rounds from before 1905, with its round nosed bullet. On the right is a 7.92x57mm Turkish round, loaded with an S Patrone type spitzer projectile, which became the pattern for military rifle rounds after 1905.

This improved effectiveness has caused controversy to this day regarding the legality of certain types of bullets, discussed in more detail in this article. The high muzzle velocity, lighter weight, and better aerodynamics of the new “spitzer” bullets versus their round-nosed predecessors, coupled with requirements for new bullet types such as tracer, anti-balloon, and armor-piercing, halted temporarily the drive for smaller calibers. Many and services had up to this point adopted calibers as small as 6mm, and experimented with ones as small as 5mm, but for the next 50 years (from 1904 with the adoption by Portugal of the 6.5×58 Vergueiro to 1954 with the adoption by Venezuela of the short-lived 7x49mm Liviano) no new chamberings smaller than 0.298″ would be adopted as standard by a major military force. In fact, several countries, including the Japanese, French*, and Italians, would switch from smaller chamberings to larger .30 caliber rounds during this period.

The 6.5x54mm Mannlicher-Schoenauer on the left was adopted by the Greek Army in 1903, and was one of the last calibers below 0.298″ bullet diameter adopted by a major power for fifty years. On the right is the 7x51mm FN/Liviano, adopted in 1954 by Venezuela for their FN FALs.

Since the introduction of the metallic cartridge, chamberings intermediate in power between a standard rifle cartridge and pistol ammunition were used in special roles to augment the firepower of special infantry units. These rounds weighed and recoiled far less, while delivering more range and effectiveness than standard pistol rounds, making them highly suitable for use in rapid firing weapons. However, until the mid-1940s, these weapons were considered specialist items, unable to meet all the requirements (particularly the long-range capability desired in machine guns) necessary for a standard issue round. During World War II, however, the value of individual automatic weapons in the form of expedient-to-produce pistol-caliber submachine guns proved that organic automatic firepower was a requirement for the infantry in the second half of the 20th Century. For the Soviet Union, after their experience fighting against Germany during World War II, this meant the adoption of the intermediate 7.62×39 caliber as the standard round of the squad, but the Western powers would take a more conservative path.

This apex of the full-power cartridge came with the de-facto standardization of the American .30 Light Rifle cartridge within NATO in 1953, leading to the familiar 7.62x51mm NATO caliber. This round was essentially a shortened “economy” version of the traditional .30 caliber round that had dominated small arms developed for the past half-century, having been developed explicitly by the United States to save brass and allow a shorter length action for automatic weapons. Thanks to the US preference (and NATO’s inability to say “no” to their key member) for a universal full-power round, it defeated its British intermediate .280 caliber competitor, leaving the UK with somewhat bruised national pride. However, not even the US could ignore the value of the intermediate round for long.

Left: The 1.95″ long case FA T1E1 round, a prototype for what would become 7.62x51mm NATO. Middle: The .280/30 British, with a 140gr steel-cored pink-tipped Type C bullet. Right: 7.62×39 FMJ.

*In the case of the French, they had adopted – but not successfully standardized – the 7mm Meunier (one of several unsuccessful “military magnums” of the brief period between 1905 and the end of WWI), only to abandon it after 1918 and adopt in the 1920s the .30 caliber 7.5x54mm.

3. Small Caliber, High Velocity

This brings us to the modern paradigm, called “small caliber, high velocity” (SCHV) in literature. This was essentially a rebirth of the concepts trialed in the late 19th Century – whereby a smaller, lighter projectile driven at higher velocities would give a flat trajectory, good penetration, light overall weight, and low recoil – but coupled to a new context. While the small caliber high velocity rounds of the 19th Century focused on achieving ever longer effective range, the new SCHV of the latter half of the 20th would focus on giving the lightest possible weight, lowest possible recoil, and the highest possible effectiveness out to medium ranges. The standard bearer for this concept was the US 5.56x45mm round, still in use in modified form today. Development of the SCHV concept began in that country in the early 1950s, based on research conducted in the late 1920s and during World War II and Korea. Experiments began with modified M2 Carbines chambered for .22 caliber centerfire rounds, and subsequently evolved into a standard infantry rifle ammunition concept that would halve the weight of ammunition carried by the infantryman while retaining most of the effectiveness out to short ranges. This, coupled with a lightweight automatic weapon in the form of the AR-15, proved to be a much more modern and overall effective combination than the previous full-power 7.62 NATO caliber infantry rifles. In 1963, the United States Army adopted the AR-15 as the “XM16E1” and the 5.56mm round as “M193”, in theory as a temporary solution until development of the extremely advanced even higher velocity flechette-firing Special Purpose Individual Weapon could be completed. It never was, and in 1970, after infamous teething troubles with the ammunition and rifle barrels in the Vietnam War, the “stopgap” M16 was made standard issue by the United States, replacing the M14 as the primary arm for US GIs.

US Army caliber concepts of the 1950s and 1960s. Left: The .22 Aberdeen Proving Ground Carbine, designed for the M2 Carbine and the precursor to all modern SCHV rounds. Middle left: 5.56mm M193. Middle right: 7.62x51mm M198 Duplex. Right: XM216 flechette, from the SPIW program.

The AR-15 and its lightweight ammunition sent shockwaves through the world of infantry small arms, in both the West and the East. With the US adoption of an intermediate round just a decade after they pushed the full-power 7.62mm round onto NATO, the Organization turned to yet another competition to determine a second standard round, before domestic intermediate caliber developments could ruin the NATO standardization agreements. The competition featured entrants from the USA, France, Belgium, Germany, and the UK, but the winner was the SS109, a Belgian loading of the 5.56x45mm, which became the basis for NATO-standard 5.56mm ammunition, including M855.

In the Soviet Union, work had begun as early as 1959 on an SCHV round that could match or beat the American 5.56mm M193. The story is told in more detail here, but the round that resulted in 1967 was the 5.45x39mm, standardized with the 7N6 loading in 1974.

Modern SCHV rounds. Left: Danish 5.56mm SS109. Middle: Korean 5.56mm M855. Right: Soviet 5.45mm 7n6.

China, paralyzed by Mao Zedong’s rigid economic policy, remained mostly dormant in the field of small arms until the restructuring undertaken by his successor, Deng Xiaoping, who took office in 1981. Several Chinese military programs gained momentum in the subsequent years, including a program for a modern general purpose SCHV cartridge, which became the twin 5.8x42mm DBP-87 and DBP-88 rounds. These replaced the 7.62×39 and to a more limited extent the 7.62x54R cartridges in Chinese service, but in having two distinct loadings with different overall lengths fell short of being a truly unified solution, and so in the early 2000s development of a single round that could replace both 5.8mm loads began, finalized in 2010 as the DBP-10.

This “triumvirate” of SCHV rounds represents the current state of the art of infantry small arms ammunition today, supplemented by the older full-power cartridges for larger support weapons like marksmen’s rifles and machine guns. As nations gained experience with the new small-caliber rounds, their disadvantages and limitations became more apparent. Most SCHV rounds from the 1980s on were optimized for penetrating power at ranges beyond the short-medium distance that the concept was originally designed for, sacrificing to one degree or another closer-range shock effect and “stopping power” (a term of convenience that remains too nebulous to truly define). In addition, despite incorporating tough bullet construction and armor-defeating steel cores that extended their nominal range, the effectiveness of these rounds at distances beyond 500m seemed to be significantly below that which was desired, and as a result every nation has kept in service older .30 caliber ammunition: The 7.62x51mm NATO in the case of the Western nations, and the 7.62x54mmR in the cases of Russia and China. This use of two rounds in tandem, instead of one universal one, was and is to many a suboptimal arrangement. In short, despite the resounding success of the SCHV concept, there was significant room for improvement.

4. Alternatives and their limitations

The immediate conclusion that many watching the problem came to was that the SCHV concept was inherently flawed; no amount of improvement within the existing chamberings would bring the ammunition to the desired level of effectiveness. Almost universally, these thinkers believe that the projectile weight of the 5.56mm round is too low, and virtually every would-be replacement caliber uses a heavier bullet, usually at lower velocity. We can group these proposals into two basic categories:

(A) includes the 6.8mm Remington SPC and the .300 AAC Blackout, and were designed around requirements to improve effectiveness from short-medium range only. As a result, these rounds typically have poor form factors and ballistic coefficients, and their advantages vs. 5.56mm diminish with range. Almost all utilize bullets over 100 grains in weight, with moderate muzzle velocities between 2,100 and 2,600 ft/s, and as a result typically have poor to mediocre trajectory characteristics. Together, this group essentially represents a line of thinking centered around replicating and/or improving upon the old Soviet 7.62×39 caliber, but for the existing AR-15 platform. As a result of their poor ballistic characteristics and substantially greater weight (25-50% more than 5.56mm), there is very little case for these rounds as standard issue military calibers, although they may be intended or adopted for specialized applications (e.g. subsonic .300 Blackout). However, this group has also received by far the most development, with military-style armor-piercing, ball, tracer, and other loads existing for both the 6.8mm SPC and the .300 Blackout.

(B.) includes the 6.5 Grendel, .264 USA, 7x46mm UIAC, and several other wildcat cartridges, and represents an attempt to replace both 5.56mm and 7.62mm with a single round. Perhaps the most vocal proponent of this path is the British small arms author Anthony G. Williams, whose “General Purpose Cartridge” (GPC) concept he proposes as a unified solution for the infantry rifle squad. It centers around a medium-velocity (2,400-2,800 ft/s) round firing very low drag bullets of caliber between 6.2-7mm with the aim to create as efficient a round as possible with respect to recoil felt at the shoulder, overall cartridge weight, and delivered energy at longer ranges (beyond 800m), often with an emphasis on matching existing 7.62x51mm M80 Ball. The pitfalls of this concept are its substantially greater weight than 5.56mm (40-80% more), size (which also implies a larger weapon), and recoil, making the development of lightweight automatic weapons much more challenging. Further, the optimization of the round for such simple metrics as retained energy for a given size and/or weight carry with them potential compromises that may invalidate the concept for military applications, such as a low improvement in demonstrated effectiveness, incompatibility or poor compatibility with lead-free bullets, tracers, and other types of projectiles, and disappointing real-world ballistics resulting from “nickel and dimed” performance estimates during the concept stage. Although Williams sees this round as the clear unified small arms ammunition solution, it has so far not been been well-proven, and the weight disadvantage versus possible smaller caliber solutions remains largely unaddressed. Even so, if the adoption of a single round to replace both 5.56mm and 7.62mm is taken for granted, then Williams’ proposal does present the most intuitive solution. I discuss this concept in more pointed detail in posts on my own blog here, here, here, and here.

Assorted longer-ranged intermediates. Leftmost is the 6mm SAW, designed to give better penetration to automatic riflemen in the US rifle squad. Middle-left is the Swiss 6.45x48mm GP80, an experimental predecessor to their 5.56x45mm GP90 round. The two rightmost: 6.5×38 Grendel, designed by Bill Alexander to improve the long-range performance of AR-15s.

5. Improving SCHV

In response to concerns about the lethality of both 5.56mm M855 and 7.62mm M80 Ball, the Army undertook a program to provide ammunition of superior effectiveness to the troops, which was fully compatible with existing weapons. The Marine Corps, too embarked on their own program to improve small arms effectiveness, and the results of these programs were the Army’s 5.56mm M855A1 and 7.62mm M80A1 EPR, and the USMC’s 5.56mm Mk. 318 and 7.62mm Mk. 319 SOST rounds. All four rounds utilized advanced bullet design based on extensive research to greatly improve the penetration and terminal effect – and especially the consistency of terminal effect – versus their predecessors. Further discussion about the “fleet yaw problem” these teams faced, and its solutions, can be read here.

Next generation solutions could also come in the form of calibers at or close to 5.56mm. The ogive space of the current 5.56x45mm envelope is decidedly not optimum, which limits how aerodynamic the bullets can be for cartridges loaded in that caliber. A cartridge that utilized a longer ogive length, akin to what Williams proposes for his 6.5mm round, could substantially improve performance versus the existing short-ogive rounds. A good example that exists today is the Soviet/Russian 5.45x39mm round, which achieves an 11% weight reduction versus 5.56mm, while giving slightly superior external ballistics. Projectiles more streamlined than even those of the 5.45x39mm are possible, too, which could be used alternately to save weight versus current 5.56mm or improve performance at the same weight or with minimal weight increase.

Two .224 caliber improved SCHV cartridges flanking a Williams-style 6.5mm GPC. The cartridge on the left matches the middle 6.5mm cartridge in muzzle velocity with a bullet of the same design, while being substantially lighter, while the cartridge on the right has a substantially flatter trajectory for the same heat flux. Both of the .224 caliber cartridges weigh within a gram of M855, while the middle round would weigh 40-50% more. All three cartridges were created and rendered by the author.

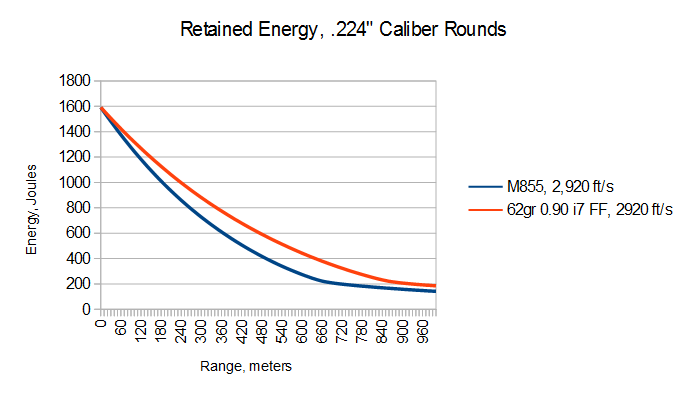

It’s commonly said in small arms ammunition discussions that “5.56mm is at the limit of its development”, but while that’s truer for the 5.56mm chambering as it exists today, it is absolutely not true for the .224″ caliber as a whole. By changing only the shape of the projectile to a lower drag one, major performance gains are possible, illustrated by the graph below:

Changing the bullet shape of M855 from one with a 1.15 i7 FF to one with a 0.90 i7 FF improves the performance considerably. The energy of the round with the lower form factor, shown by the red line, is the same as M855 for these range values: 390 meters vs. 300 meters (M855), 650 meters vs. 500 meters (M855), and 1,000 meters vs. 770 meters (M855).

Future small arms ammunition engineers should take care not to ignore the potential of .224 caliber rounds to provide an effective, lightweight round.

6. The future

One thing not yet mentioned is very clear: For the moment, existing 5.56x45mm and 7.62x51mm ammunition (especially the new EPR and SOST series) is satisfactory, and a new brass-cased round of any kind is very unlikely to be adopted. The matter then turns to what the future small arms ammunition configuration should look like, given a paradigm shift like lightweight cased or caseless rounds. As much as we may want there to be, however, there isn’t an easy answer here; mentioned previously was the complexity of the problem, something that can only be worked through via thorough research and empirical testing. This groundwork, if yet laid, hasn’t been released to the public, and that sets a limit to the speculation amateur theorists like myself can confidently make. Key questions include whether the next configuration includes two rounds like the current one, or tries to unify them into just one, the answer to which depends on whether the logistical benefit of a unified round outweighs the increased load on the infantry of a heavier general-issue round. Also, determining the needs of the infantry squad, and how a new round fits in with their tactics, level of training, and inherent limitations is absolutely requisite: A round optimized for the best performance at over a kilometer does not do very much good if the soldiers using it are only effective marksmen out to a third of that. Likewise, a round with the best ballistics in the world doesn’t mean much if the empirical improvement in effect versus a smaller, lighter round is low. Conversely, adopting a round which is too short ranged or too weak, leaving the infantry at a disadvantage versus current and potential enemy individual weapons, should be avoided. Thus, great care should be taken in laying down requirements to achieve a solution that will give requisite effectiveness with the minimum weight.

Fortunately, the technology on the horizon is poised to assist with this last concern. The Lightweight Small Arms Technologies program was created to investigate lightweight weapons and ammunition, chiefly telescoped polymer-cased and caseless configuration cartridges. The telescoped ammunition concept is where the projectile is buried within the propellant, and then ejected from the combustion chamber in the earliest stage of ignition, therefore creating a smaller, more compact overall package. It comes with a number of nontrivial disadvantages related to barrel wear and propellant waste, which have been circumvented in the latest incarnation of LSAT’s Cased Telescoped Ammunition (CTA) by reducing the degree to which the projectile is buried in the case, and by fitting the case with a sealing gasket. Supplementing this effort has been conventionally-shaped composite (metallic/polymer) cased ammunition, as well as aluminum- and thin-walled steel-cased experimental configurations – this last having reached a high enough level of development to appear in the PEO Ammunition Systems Portfolio Book for 2013. These technologies offer weight reductions compared to current brass-cased ammunition of anywhere from 20-40%, savings that can be applied in varying degrees to either lighten the soldier’s load, or improve his effectiveness without adding weight. They all come with one caveat, however: Because they lighten the case of the cartridge, and no other component, they are not a magic mass-vanishing wand. The heaviest component of the loaded rifle cartridge is the projectile, so even lightweight ammunition must still be very carefully designed according to the same principles as conventional brass-cased ammunition to achieve the lightest possible weight for the desired performance.

Lightweight ammunition is nothing new, but thanks to modern materials science it just might have a breakthrough soon. Here are some previous lightweight developments, left-to-right: .30 Light Rifle T65 aluminum cased, .280/30 British aluminum cased, 4.73×33 DM11 caseless.

7. To conclude

New technologies point the way for lighter, better small arms ammunition, but military outlets are interestingly quiet on the subject of the actual size and shape of next generation ammunition. There are benefits to both single- and dual-caliber systems, and any evaluation of the current and near-future state of the art must take both arrangements seriously. While the next ammunition configuration may not be publicly known, it is very clear that there may be serious consequences for carelessness in selecting a new caliber, especially in the case of the single-caliber concept. The adoption of the powerful 7.62 NATO in the 1950s, along with the troubled M14 rifle, created a need for a lighter, softer-shooting weapon that was eventually filled by the M16 and its 5.56mm round, which became the basis for today’s excellent M4 Carbine and its M855A1 round. However, in the rush to get rifles and a completely new type of ammunition to Indochina in the late 1960s, the implementation of correct standards and quality control were neglected, and many soldiers lost their lives as a result. The round, or rounds, that become the basis for the new generation of small arms will require a great collective labor of research and testing to achieve the best balance of characteristics and to avoid a critical gap in capability.

Your Privacy Choices

Your Privacy Choices