What if the Mini-14 had arrived over a decade earlier, and been a pound lighter? Would it have still played second-fiddle to the AR-15, or would US troops be using classically-lined rifles of wood and steel right up until today? Was there really an alternative to the “Buck Rogers” space-gun-like AR-15 in the late 1950s and early 1960s?

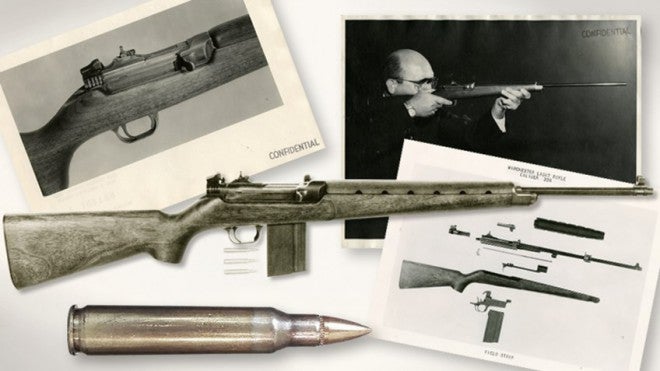

It turns out that such a gun did exist. The Winchester Lightweight Military Rifle has been a perennial favorite among commenters here at TFB ever since an evaluation of the rifle was featured in a 2014 Weekly DTIC article. Since then, I’ve been considering at some point writing an overview of the rifle’s short development history for our readers, but I no longer have to. The excellent Bruce Canfield, writing for American Rifleman, has gotten to the LMR before me, and written a better treatise on Winchester’s impressive SCHV rifle than I could have:

By the mid-1950s, it was proposed that the ideal rifle would be a selective-fire (capable of full- and semi-automatic fire) rifle weighing no more than 6 lbs. with a 20-round detachable-box magazine. The desired cartridge would be a high-velocity .22-cal. center-fire chambering capable of completely penetrating a military-style helmet at a range of 500 meters. The proposed cartridge was mandated to fire a 50-to-55-gr. bullet at a muzzle velocity of approximately 3,000 f.p.s.

Since there was not an infantry rifle in our small arms arsenal possessing the desired attributes for the proposed “infantry rifle of the future,” the U.S. Army Continental Command (CONARC) solicited proposals from several sources for such an arm. Two of the entities submitting proposals were the Armalite Division of the Fairchild Engine and Airplane Corp. and the Winchester-Western Division of Olin Mathieson Chemical Corp. Although they were faced with the same design parameters, the companies tackled the project from different directions.

Winchester had already taken advantage of the talents of genius-psychopath David Marshall Williams to produce a series of fantastically light and sound weapons in everything from .30 M1 Carbine to .50 BMG caliber, although none were ultimately produced in quantity. It was this basic mechanism that set the foundation for the Lightweight Military Rifle:

On the other hand, rather than develop a totally new arm, as was the course taken by Fairchild and Stoner, Winchester based its design for the proposed new rifle on guns the company had already developed during World War II. During the war, Winchester had engaged the services of a talented, but sometimes volatile, gun designer named David Marshall Williams. Williams had previously designed the short-stroke gas piston that was used on the famous M1 carbine. Winchester also utilized the same basic gas system design on several prototypes it developed during the war, including the G30 series of rifles that the company hoped might supplant the M1 Garand rifle and the Winchester Automatic Rifle (WAR) that was intended to take the place of the BAR (Browning Automatic Rifle) (Sept. 2015, p. 72). Only very limited numbers of the G30 or WAR were fabricated and tested, and none were adopted by the U.S. military. Nevertheless, both functioned reasonably well during the various World War II tests, so Winchester dusted off the blueprints for these guns in order to come up with an entrant to meet the new CONARC specifications. Since Williams was no longer actively employed by Winchester, the new “Light Rifle” project was headed by Ralph E. Clarkson, a member of the company’s design and engineering team. The company designated the new gun the “Winchester Light Weight Military Rifle” (WLWMR).

A Winchester employee fires a variant of the gun fitted with a sporter-type stock and a longer barrel. Note there is no front sight fitted.The design philosophy for it was described by Winchester in a 1958 manual: “From the very beginning of the development work on the Winchester Light Rifle it was considered of utmost importance that reliability must not be sacrificed to obtain low weight. As a consequence, a policy decision was taken that the new Lightweight Rifle was to be designed on the basis of well-proven earlier guns whose field reliability had been established through extensive testing. As a result, the best elements were taken from the Winchester .30 Caliber Experimental Light Rifle, the G30R Semi-automatic Rifle, the WAR Automatic Rifle and the .50 Caliber Semi-automatic Anti Tank rifle, to serve as a basis for development of the Winchester Lightweight Rifle.

Both the G30M and William’s Carbine (Light Rifle) were fantastically light firearms, the former being a selfloading .30-06 rifle that weighed a mere 7.5 lbs unloaded, and the latter being a mere four pounds unloaded in the .30 M1 Carbine caliber. These weapons were – from a weight perspective – a fantastic basis for a new small-caliber, high velocity “light rifle”. However, the Armalite was an even more modern and sound design that, although it was not as light, showed the way for infantry small arms in the second half of the 20th Century:

“Winchester then found that the new generation of U.S. Army people were mostly the type that became enthralled with what old timers and ordnance people called ‘the Buck Rogers Armalite rifle.’ These people believed that the Armalite, despite its complex and unorthodox design, would prove superior to any military rifle yet developed. Winchester, a builder of conventional arms, believed competing [against] people who thought that way would not be productive.”

Given these considerations and other issues, Winchester decided against further development of its .224-cal. Light Weight Military Rifle. With the decision made to bow out of the Light Weight Rifle competition, Winchester accepted a contract to manufacture the newly adopted M14 rifle and subsequently produced 356,501 of them between 1959 and 1964.

…

One wonders what the current American military rifle would look like today if Winchester had decided to pursue continued development of its .224 caliber Lightweight Military Rifle. It is probable that the M16 would still have been adopted, and Winchester would have wound up with a costly prototype on its hands that was of no interest to either the military or the commercial markets. Like the old adage goes, sometimes you have to “know when to hold ’em and know when to fold ’em.”

In fact, the LMR could have been an excellent commercial offering, as the Ruger Mini-14 proved. Without the need to troubleshoot the design to the degree that it could pass rigorous military tests, Winchester could have focused on readying the tooling of the similar LMR for civilian sales. Instead – and as Canfield notes, not ill-advisedly, either – Winchester pursued a production contract for the new M14 rifle. It’s difficult to tell how successful a civilian LMR could have been, but the later Ruger Mini-14 has been estimated to have sold approximately a million units since its introduction in 1973. Against even that retrospective possibility, a contract for potentially millions of M14s, up front and for sure, must have seemed like the better choice.

Your Privacy Choices

Your Privacy Choices