The M1 Carbine is a weapon that, although popular with shooters and soldiers alike, has been unfairly dismissed in the broader context of the development of the modern assault rifle. Although initially fielded without select-fire capability, the lightweight and handy M1 Carbine was a surprisingly capable weapon, able to perform the combat roles of both the full-size infantry rifle and to a more limited extent the submachine gun, out to short distances. Its development would foreshadow the post-war assault rifle, and both it and its cartridge would become a model for several post-war intermediate caliber assault rifle projects in France, Belgium and elsewhere.

A US Army crew chief holding a select-fire M2 Carbine as he looks out the door of his UH-34 Choctaw helicopter in 1963. Image source: milsurps.com

Perhaps the lowly Carbine has been overshadowed by the much larger and more impressive-looking MP.44 Sturmgewehr used by the Nazis during the war, or maybe the post-war sale on the civilian market of Carbines almost exclusively of the semi-automatic-only M1 variant has kept the rifle off the radar of post-war assault rifle historians, but the little rifle deserves a second look at its importance in the broader history of the modern select-fire infantry rifle. This post will not cover in-depth the M1 Carbine’s history, but will instead make the case to any historians – amateur or professional – reading it that the Carbine is worth reconsidering as an important milestone in the development of the assault rifle.

A US infantryman, possibly a Paramarine, fools around in the Pacific Theater with an M1A1 Carbine paratrooper variant. He has chosen the minimum of camouflage in the hot climate. Image source: usmilitariaforum.com

Development of the M1 Carbine, at the time called the “Light Rifle” (not to be confused with the later Lightweight Rifle program covered in another ongoing series of mine) began in earnest in the fall of 1940. In the years preceding, requests had been generated within the US Army for a supplemental weapon to the new M1 Garand, which would provide a lighter weight, more convenient combat tool to soldiers in the ever-growing logistical tail of the force. The cooks, mechanics, drivers, secretaries, pilots, paratroopers, etc of the US Army could all use a weapon much lighter and handier than the standard M1, which, fully loaded, weighed about ten pounds. Most relevant to our topic, the initial specifications for the Light Rifle dictated a weapon capable of select-fire, that could fire semi-automatically as a rifle would, or fully-automatically, like a submachine gun. The solicitation reads:

j. The rifle is to be of the self-loading type, capable of being fired either semiautomatically; that is, one shot for each pull of the trigger, or it shall be possible by the operation of the selector to fire the weapon automatically. Selector change shall be made only with a special tool.

Equally relevant, the solicitation also included a requirement for high-capacity magazines:

d. The rifle must be designed with a box magazine which may be fed from clips or chargers. Magazines with capacities of 5, 10, 20, and 50 rounds should be supplied. [emphasis mine]

In the summer of 1941, due to the protests of the inventors and the results of firing tests showing a limited utility, the fully automatic requirement for the Light Rifle was eliminated, and with it the 50-round magazine requirement, to expedite development time. This was a sound decision that allowed the swift selection of the winning Light Rifle – Winchester’s entry by William C. Roemer and Fred Humeston, based on David Marshall Williams’ work – and its selection in October 1st of 1941 proved the merit of Ordnance’s logic. The Light Rifle program had taken a mere 16 months from appropriation of funds to the selection of a design for production, and as a result the M1 Carbine’s production began in earnest in August of 1942. The production of the new Carbine during World War II is one of the era’s great industrial success stories, with 9 firms and numerous subcontractors producing 6,221,220 of the weapons between the start of production and the end of the war. The emphasis on the rifle’s tremendous production history should not be missed: It is a necessary – though often-ignored – characteristic of the assault rifle that it must be cheap and easy to produce, or else it can only be a specialist weapon and not a standard-issue replacement for the conventional rifle. Although it did not enter service with the select-fire hallmark of the German Sturmgewehr, it was produced in far, far greater numbers (more than 16 times the number M1/M2 series of Carbines were produced than that of the German Sturmgewehr series, despite production occurring over a similar period of time).

One Lt. Fred Kent assists Betty Brewer in firing an M2 Carbine equipped with a paratrooper folding stock. Kent is (probably erroneously) listed in the period description of the photo as the inventor of the M2’s fully automatic mechanism. Image source: usmilitariaforum.com

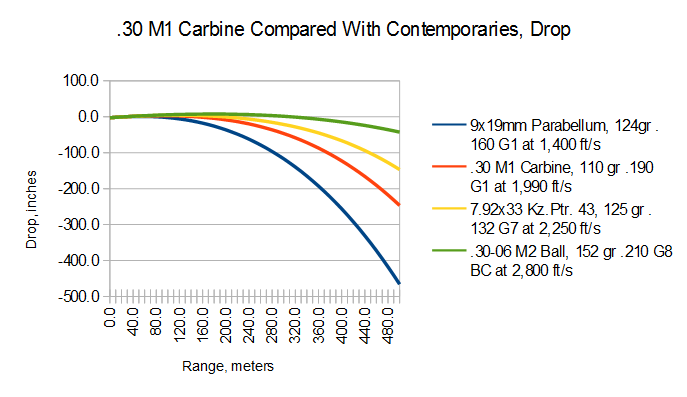

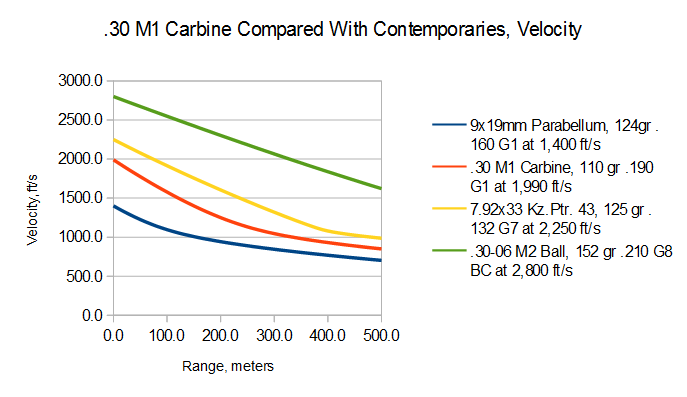

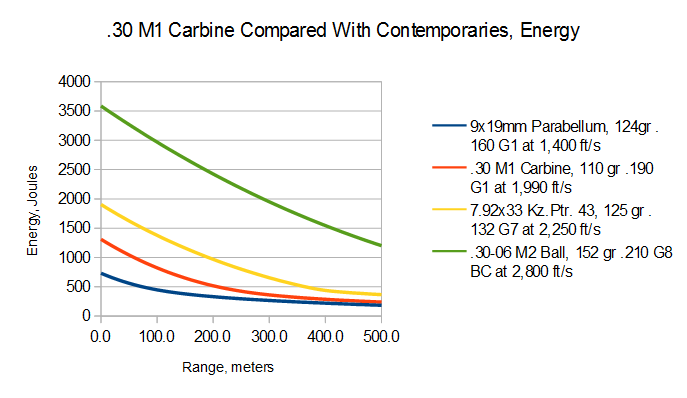

Starting before D-Day, the development of a select-fire variant of the Carbine brought the program full-circle, and the M2 Carbine with full “rock-n-roll” capability was accepted for service on September 14, 1944. Even with this, however, some may raise objections to calling the little rifle a true “assault rifle” citing its especially poor ballistics. While it’s true that the .30 M1 Carbine caliber is underpowered compared to other “intermediate” calibers, let’s reconsider it for a second, too:

What is evident here is that the .30 M1 Carbine caliber is actually closer to the 7.92 Kurz caliber of the German Sturmgewehrs with respect to trajectory and velocity than it is to either the 9mm Parabellum pistol round of the British Sten and German MP.40 submachine guns, or the .30 M2 Ball rifle round of the M1 Garand. For some points of comparison, the .30 M1 Carbine possesses the same bullet drop at 300 meters as the 9mm Parabellum does at 220 meters, or the 7.92mm Kurz at 360 meters. It possesses the same energy at 300 meters as the 9mm Parabellum does at 160 meters, meaning it is still lethal at that range – although significantly less destructive than the 7.92 Kurz, which equals that energy at 510 meters. In terms of trajectory, velocity, and energy, the .30 M1 Carbine is certainly a lethal round at the “magic” 300 meters normally used to define intermediate rifle cartridges. The Carbine’s capabilities at this range are demonstrated in a video by TNOutdoors9, embedded below:

Indeed, the Carbine became a staple of front line troops in both Europe and the Pacific, thanks to its balance of capability, great handling, and excellent availability. Far from being “just” an echelon weapon, the Carbine was instead an extremely relevant weapon of battle, in fact Carbines captured by the Germans received the designation Selbstladekarabiner 455(a).

German soldiers, reportedly of SS Kampfgruppe Hansen, sprint across a road for a staged photo in Poteau, near the Ardennes, in December of 1944. One of them carries a captured M1 Carbine. More details on this series of photos can be found at bavarianm1carbines.com. Image source: ar15.com

Whether everyone agrees that the M1/M2 Carbine is an early assault rifle, of course, is unimportant. Instead, it’s my hope that the humble Carbine is recognized as a major development in the history of the modern intermediate-caliber select-fire service weapon and not dismissed as a mere early personal defense weapon!

Your Privacy Choices

Your Privacy Choices