This is the fourth part of a series of posts seeking to describe and analyze the 7.62mm Lightweight Rifle concept promoted by the Americans, and subsequently adopted by NATO in various forms. This series will cover development from before World War II to the present day, but will focus primarily on the period from 1944-1970, which constitutes the span of time from the Light Rifle’s conception until its end in the United States with the standardization of the M16. This article itself deals with the fully automatic variants of the M1 rifle developed before US focus shifted to the then-new, shorter .30 Light Rifle cartridge that led to the 7.62 NATO caliber. Therefore, all rifles covered in this article were chambered for the standard .30 M2 caliber, and the series of fully automatic M1 derivatives chambered for the .30 Light Rifle experimental round will be covered in a subsequent installment. In more than one way, this is the first “true” installment of the Light Rifle series, as the three preceding articles can be considered prologue material, though that does not reduce the importance of their subjects. My readers should also note that while I consulted a variety of sources to write this article, my narrative heavily relies upon Bruce Canfield’s magnum opus The M1 Garand Rifle, as well as R. Blake Stevens’ U.S. Rifle M14 from John Garand to the M21. Indeed, the title of this article is adapted from the third chapter of that latter book, as I could think of nothing superior.

You can read the other parts of the series by following the links below:

- Light Rifle 1.5: A Clarification (this was written after Part I, but should be read first)

- The Rise And Fall Of The Light Rifle, Part I: Prologue

- To Challenge A Newly Won Throne: Light Rifle, Part II

- Improving The Deadliest Rifle In The World: The M1E Series

Until this point in the Light Rifle series, all of the development we have covered has been essentially background information. The relevance of projects like the Pedersen and Johnson rifles will become clearer as we go along, but until now we haven’t actually begun to talk about the U.S. Army’s decade-and-a-half long search for a select-fire full-power service rifle. This article marks our introduction to this program, but it’s also where a comfortable narrative about exactly what was going on that led to these weapons begins to break down. As we’ll see, Army Ordnance would become very familiar by the end of the Second World War with full-size select-fire infantry rifles, but despite their obvious flaws and the sheer impossibility of meeting every desire outlined by the Army, the program would carry on for another twelve years after the Japanese capitulation. Why did they do this? There is no clear or satisfying answer to this question. In my research, I’ve found that I’ve grown more, not less, frustrated by this and other questions, and I suspect readers, too, will find themselves baffled at the inability of Army Ordnance to recognize what should have been right in front of their noses.

With that said, let’s dive right in.

The first hints of an issue rifle-derived support weapon in fact predate the development of the Garand gas-operated selfloading rifle itself. In 1919, the War Department put together a Board to determine the ideal characteristics of a new semiautomatic service rifle, incorporating lessons learned from the recent Great War in Europe. In 1920, the Board reported their findings, including this segment:

A self-loading shoulder rifle capable of a high rate of fire for short periods of time, together with the increased accuracy due to the fact that aim will not be disturbed by hand manipulation of the bolt, would add greatly to the firepower of front line troops, and probably meet all requirements as to firepower now supposed to be solved by the inclusion of a Browning automatic rifle in each squad of infantry.

In other words, in 1920 the Ordnance believed that a new self-loading rifle could actually replace not only the bolt-action M1903 and M1917 service rifles, but also the fully automatic M1918 Browning Automatic Rifle, as well, such would be the increase in firepower. This dream of standardizing all weapons in the rifle squad once again on a single type would remain with Ordnance through the 1970s.

When the United States entered the second great war of the century in late 1941, her troops were thusly armed with a general issue selfloading rifle and one automatic Browning rifle per squad. However, the desire to standardize remained. As mentioned in the second installment of this series, Ordnance was interested in finding a replacement for the aging M1918, which later led them to tap Winchester’s lightweight G30R selfloading rifle as a potential solution. If a select-fire M1 could be produced instead, perhaps the goal of the 1920 Board could be met in the process, and one standard weapon issued to all troops.

Before the first half of 1942 had ended, the United States Army was also looking to improve the M1 rifle. In the last edition of this series, we covered some of the proposed changes, including adding to the rifle a folding stock, which could potentially combine the best aspects of both the powerful rifle and the handy carbine. Further, Ordnance had cottoned to the idea of a select-fire rifle, a weapon that in theory could provide the advantages of both the selfloading M1 and the fully automatic, but much heavier, M1918 Browning Automatic Rifle. As early as mid-1942, the stage was set for Ordnance’s “do-it-all” weapon, which officers of the Department hoped could replace the Army’s mix of M1 rifles, M1 carbines, M1918 automatic rifles, and, possibly, even the M1928 and brand-new M1 Thompson submachine guns.

However, converting the M1 to an effective fully automatic weapon was easier said than done, and no less than three houses raced against each other to solve this problem. Springfield Armory, spearheaded by the genius of John Cantius Garand himself, represented the Army’s own internal development of a select-fire M1, while Remington was also contracted to develop their own solution. Winchester, in the shadow of feeling increasingly spurned by the U.S. Army, would independently develop a third select-fire, detachable magazine M1. It is these three programs that are together the subjects of this post.

Springfield Development: The T20

By May of 1942, John Garand had already begun work modifying his rifle to fire either in either the semi- or fully-automatic fire modes. This weapon, which has no formal designation, was an existing M1 rifle that was modified to use a modified BAR magazine limited to 18 rounds capacity of .30 caliber M2 ball ammunition. Testing of this rifle revealed that the additional weight of the cartridge stack of 18 rounds caused it to rise too slowly, leading to the bolt overriding the cartridge and close on an empty chamber. There were three possible solutions: Shorten the cartridge stack front-to-back, which would require a change in ammunition (keep this in mind for later installments in this series), change the magazine – which Ordnance rejected as it was desired to use existing BAR magazines – or lengthen the rear of the receiver. It was this last solution that was chosen for the new rifle design, but for reasons unknown the project was delayed until early 1944.

(As an aside, it is worth noting that to my knowledge, no pictures survive of the original select-fire John Garand prototype. Both Canfield and Stevens misidentify the Winchester prototype designed by Sefried – discussed below – as Garand’s initial prototype. Credit goes to our friend Daniel Watters for noticing this.)

It should be pointed out that all the attributes desired of the new rifle were, simply, impossible to achieve simultaneously. The Army – representing collectively the different forces of Ordnance, Springfield Armory, troops in the field, the Infantry Board, and others – wanted a rifle with select-fire capability, that was shorter (by virtue of a folding stock), lighter, still controllable and with a low enough rate of fire to replace the M1918 BAR, that used standard .30 caliber ammunition and standard BAR magazines, accepted existing rifle grenades and a flash hider, fired semi-automatically from a closed bolt and fully automatically from an open bolt, and – while satisfying all of those requirements – retained at least 85% commonality with the existing M1! Needless to say, creating a weapon that met all of these requirements at once was nothing but a pipe dream, much less doing so within a timeline that would have the rifle ready for combat during the war.

By September of 1944, construction of the first prototype of the new rifle had begun at Springfield Armory’s Model Shop, and the rifle was designated T20. The T20’s receiver was lengthened vs. that of the M1 by .3125 inches, and was adapted to use 20-round BAR magazines. In addition, the roller lug from the M1E3 replaced the solid camming lug of the original M1, and full auto fire was provided for by a connecting bar on the right side of the receiver which actuated an extension of the sear. A selector lever positioned at the rear right of the receiver in a cutout in the rifle’s stock raised or lowered the connecting bar to allow either semi- or fully-automatic fire. As per the initial Ordnance requirement, the original T20 design fired semiautomatically from a closed-bolt, and fully automatically from an open bolt. A new gas cylinder lock incorporated an integral parasol-shaped muzzle brake to control the considerable recoil forces of the new rifle, and special grooves were machined into the weapon’s barrel to help dissipate heat. It should be noted that Canfield and Stevens disagree on whether this last feature was incorporated from the beginning into the T20, or was a workaround incorporated into the T20E1 after the release of the Aberdeen test report of the T20 to Springfield Armory.

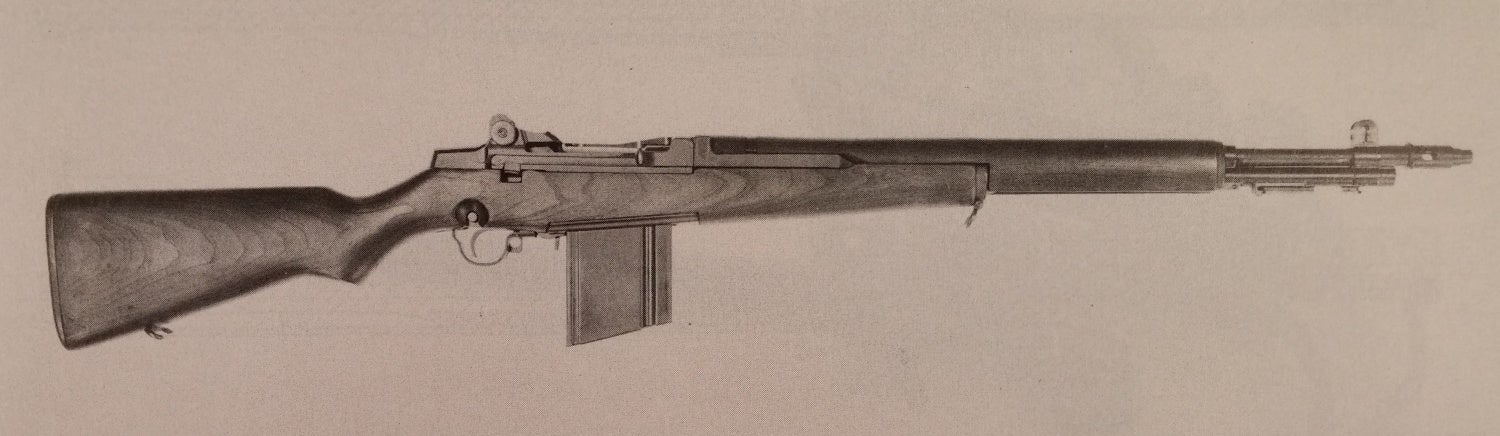

The original T20 rifle. Note the lack of a clip release latch on the side of the receiver, and the parasol-shaped muzzle brake. Image source: Stevens

In October of 1944, the rifle had been proofed and function tested at Springfield Armory, and was sent to Aberdeen Proving Ground in Maryland for testing. However, the evaluators soon found that not only did the open bolt feature not significantly improve the gun’s cook-off characteristics, but that it suffered from poor timing. Depending on where the bolt was in its travel when the shooter released the trigger at the end of a burst, the action might come to rest in either the open or closed position. Because of these problems, the open/closed bolt requirement was dropped.

Other side of the original T20 rifle. Note the selector switch above the trigger guard. The T20’s select-fire mechanism and selector switch would be retained all the way through development, and eventually used in the M14 service rifle. Image source: Stevens

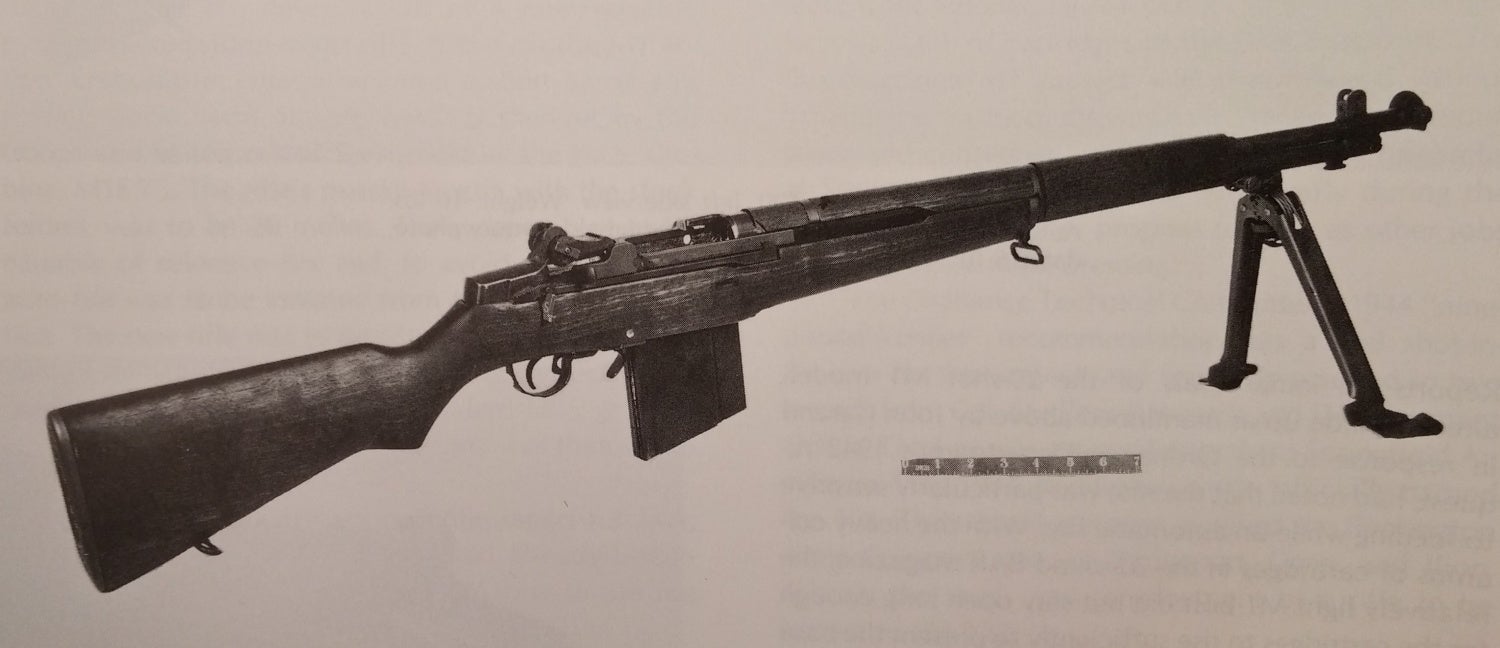

The Aberdeen report on the T20 enumerated the various flaws of the new rifle, but responded favorably to the basic concept, which resulted in the creation of a second type, designated T20E1. This rifle disposed of the open/closed bolt feature in favor of closed-bolt only operation, incorporated minor improvements to the receiver/trigger group interface, and featured an improved magazine retention design. It was also at this point that the requirement for a folding stock was dropped from the program, and a number of other requirements relaxed. The T20E1 also incorporated changes to allow it to use the M81 and M82 telescopic sights, or a grenade launching sight, and the muzzle brake was modified to allow fitment of a bayonet. Unlike the T20, the T20E1 used a pattern of magazine not interchangeable with the BAR, and had no provision for a bolt hold open besides the follower of the magazine itself. Springfield Armory engineers also added a non-removable, adjustable sheet steel bipod to the weapon.

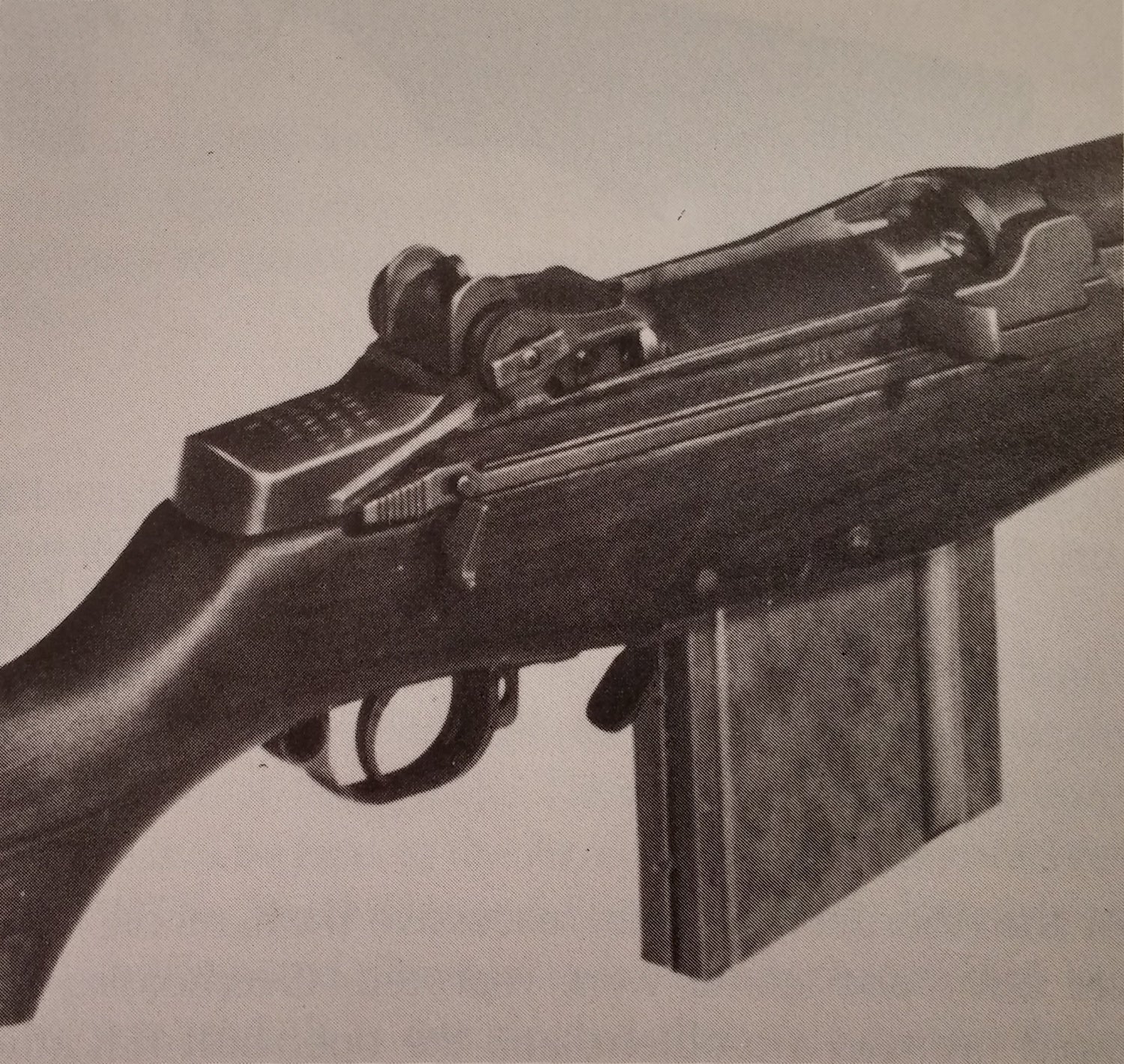

The T20E1 rifle. The parasol-shaped muzzle brake has been modified to accept a standard bayonet, and a non-removable sheet metal adjustable bipod has been added. Image source: Stevens

In late January of 1945, the T20E1 had its go at testing at Aberdeen. Perhaps giving us a rare insight into one of the primary personalities driving the project, Col. Studler reflects in his post-war report Record of Army Ordnance Research and Development, 1946:

During the period of 22 through 26 January 1945, the T20E1 Rifle was tested at the Ordnance Research Center, Aberdeen Proving Ground. This model was complete in all details, and the test results, other than the failures to feed, were exceptional. These failures to feed were caused by the bolt bearing surfaces in the barrel being soft.

Studler continues, somewhat despite himself, to describe the changes that were subsequently made to the “complete in all details” T20E1:

- Induction harden the breech end of the barrel.

- Increase length of the bipod to permit greater command height.

- Redesign the gas cylinder and gas cylinder lock screw assembly to permit ready attachment and removal of rifle accessories.

- Improve the handguard to prevent charring.

Regardless, the T20E1 rifle was considered a success, and 9 additional rifles were fabricated by April of 1945, and sent to Ft. Benning for troop trials. Studler was in fact so impressed with the new weapon that he authorized the creation of 100 limited production T20-series weapons upon the conclusion of the Ft. Benning trials, as well.

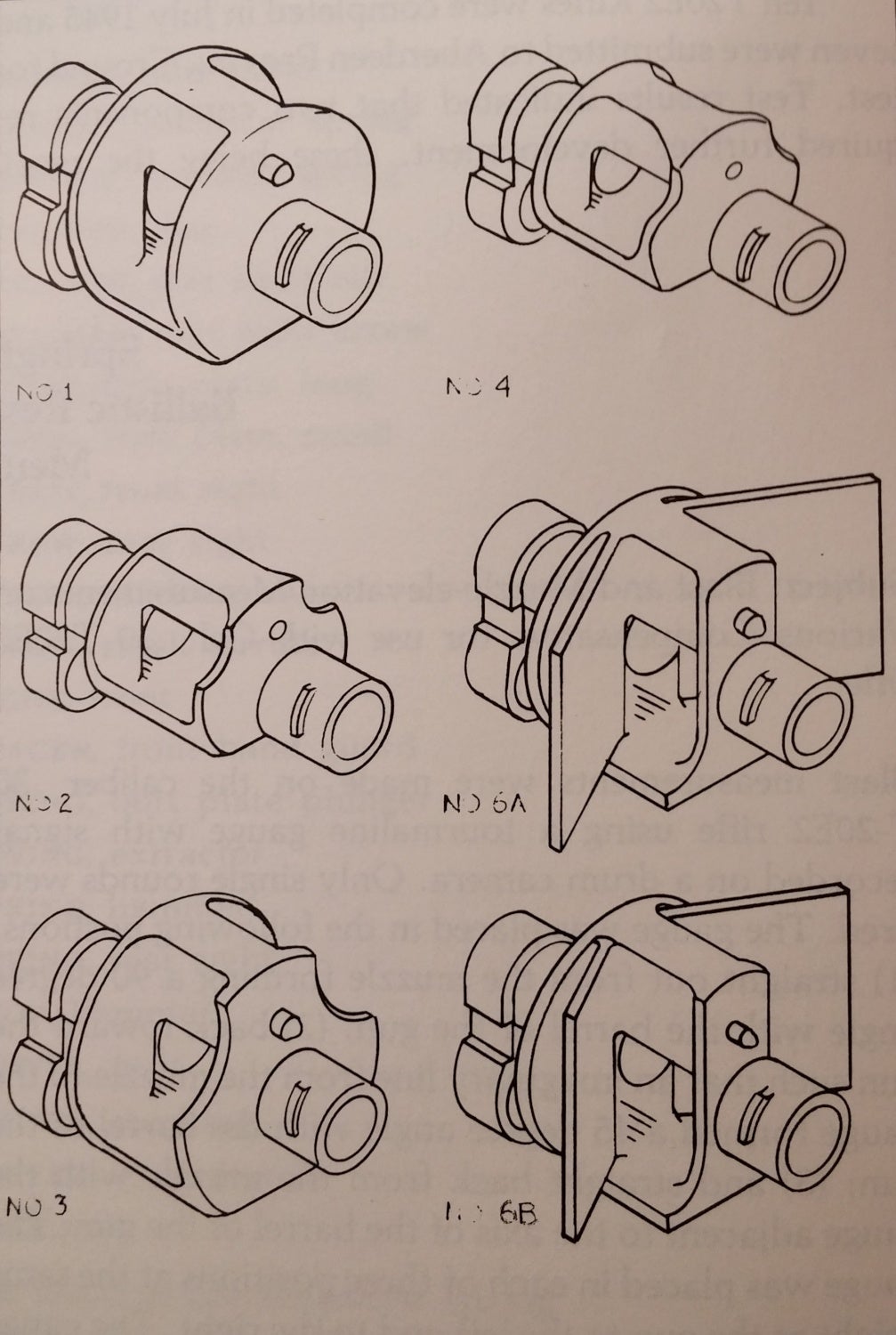

Different muzzle brake designs tested for the T20E2 rifle. The design of the rifle’s brake was absolutely essential to the concept, as otherwise the weapon would be totally uncontrollable in fully automatic mode. Image source: Stevens

At Ft. Benning, both the U.S Army Infantry Board and the U.S. Marine Corps Equipment Board tested the eight T20E1 rifles sent to them by the Model Shop. According to Studler’s Record cited above, testers found the weapons to be simple and gave them overall favorable marks. The Benning tests did, however, outline some changes that would be made to the next iteration of the design:

- Magazine to be usable in the B.A.R.

- Magazine catch to be altered in shape to eliminate the possible hazard of being accidentally depressed or damaged during rough handling.

- Provision for means of retaining the operating slide in the rear position in order that the rifle might be cleaned in the prescribed manner.

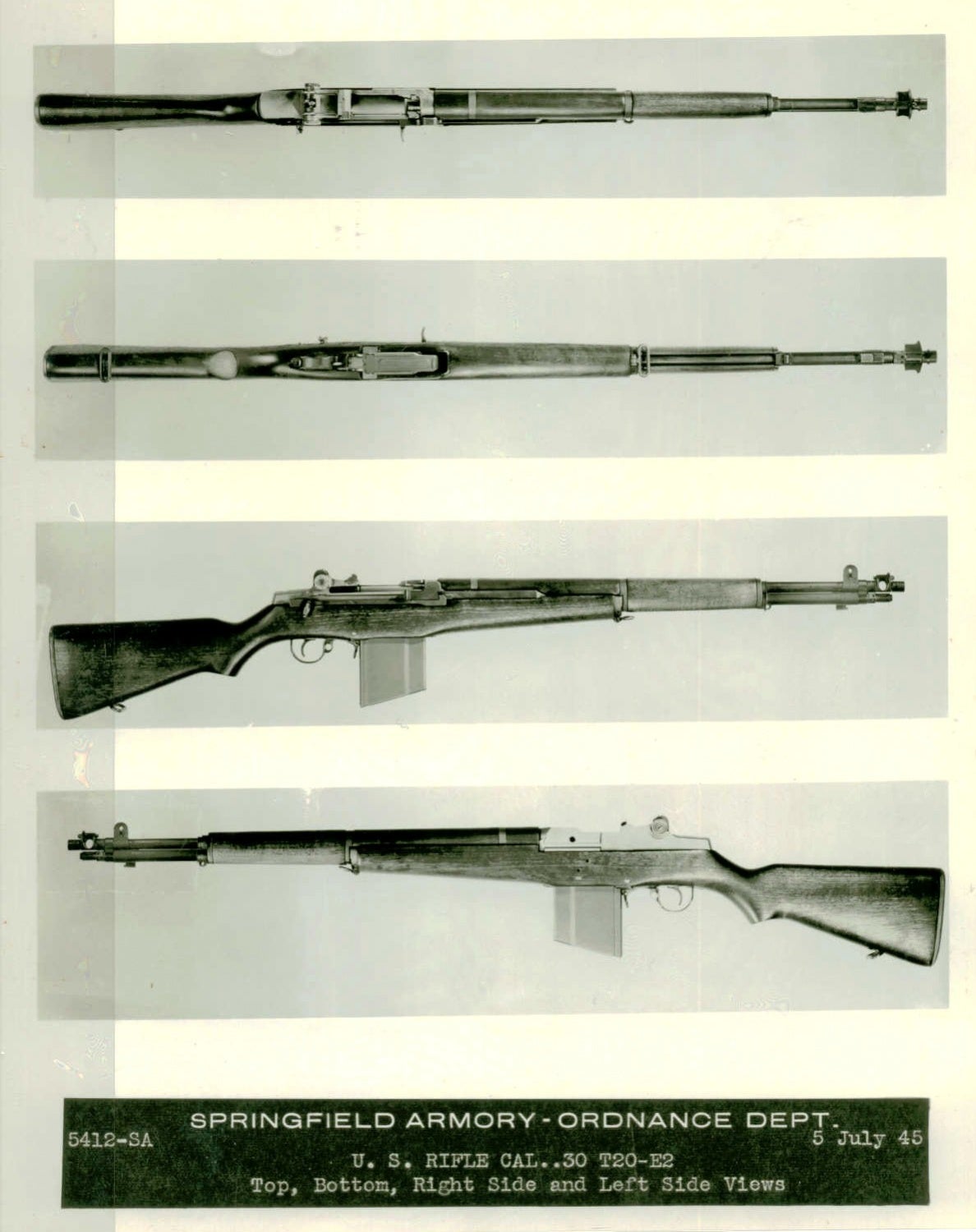

With these changes incorporated, the order for production of 100 new rifles was given to Springfield Armory in late April/early May of 1945, and on May 17, 1945, nine days after the capitulation of Germany, the Ordnance Technical committee recommended limited production and procurement of 100,000 of the finalized T20 variant, now designated T20E2, to be used against the Empire of Japan. While there is no known evidence of this being formalized, it is very likely that had the war continued, the T20E2 would have been procured (and standardized) as the U.S. Rifle, Cal. .30, M2.

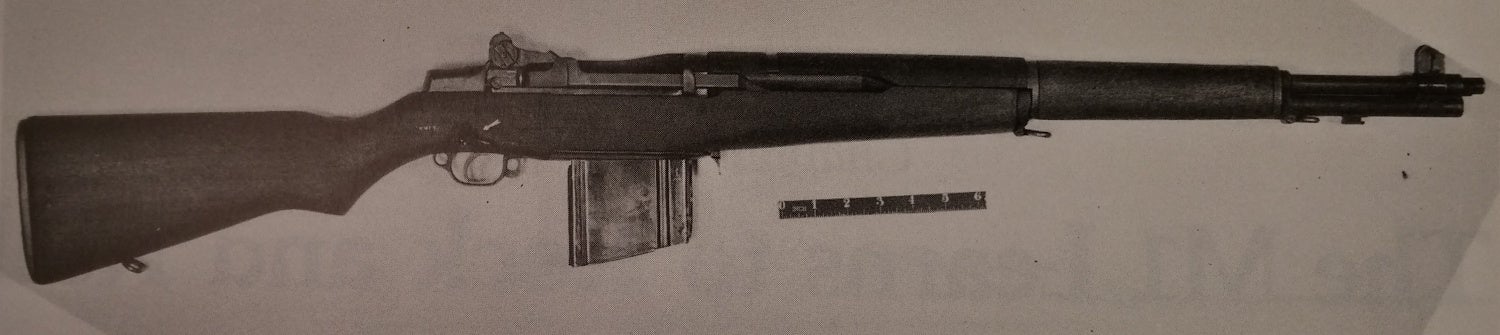

The T20E2 rifle, very nearly standardized as the Rifle, Caliber .30, M2. While it did not include open/closed bolt select fire capability, it did add a fully automatic fire mode and magazine compatibility with the M1918 automatic rifle, as well as an effective muzzle brake. The use of two much more significant weapons resulted in the stillbirth of this improved Garand. Image source: ww3.rediscov.com.

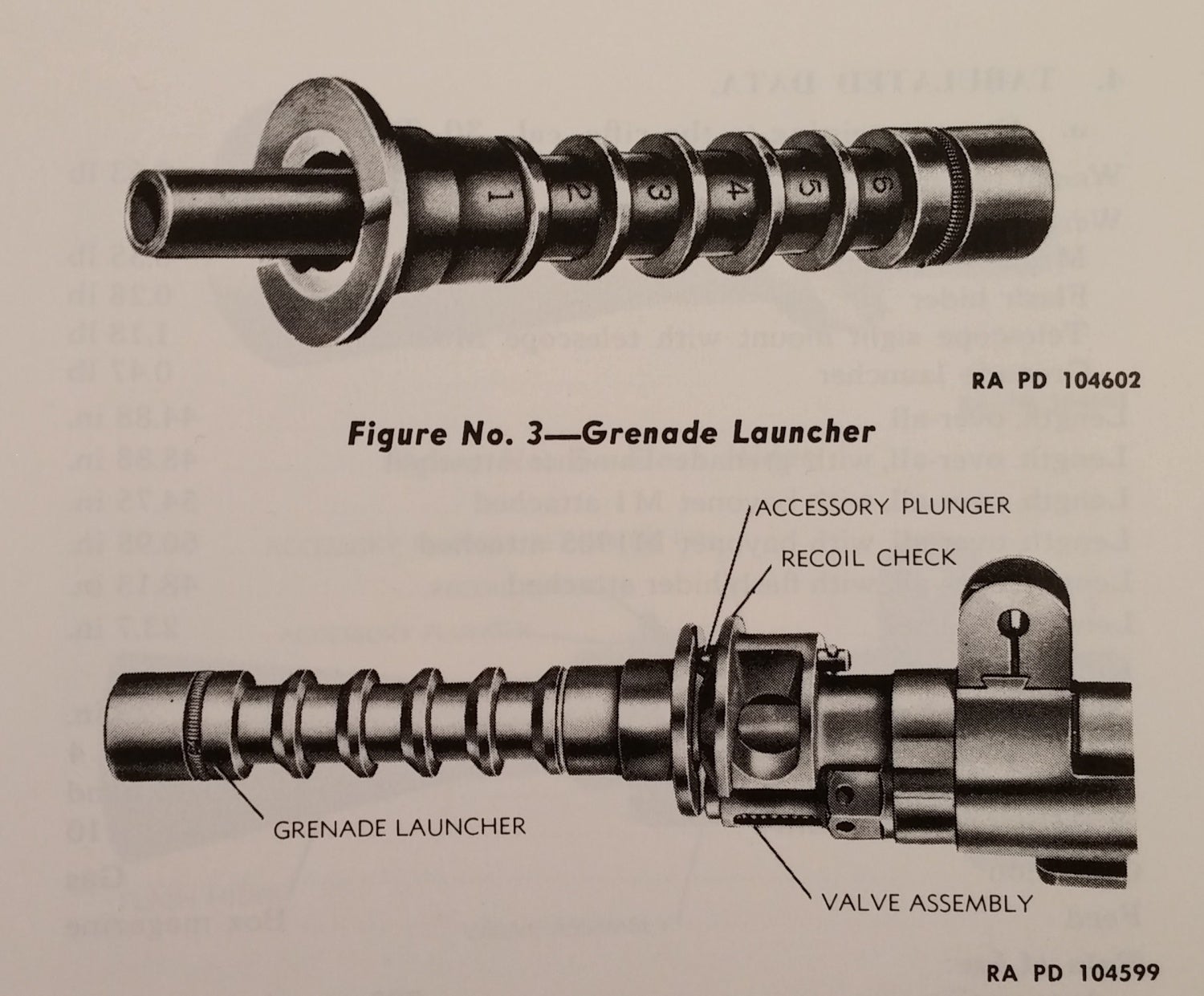

The T20E2 was compatible with a unique grenade launching device that fit over the muzzle brake of the rifle, and which was cleverly designed to shut off the brake’s ports, allowing normal grenade launching in the same manner as the existing M1. This same arrangement was used to provide the T20E2 with an effective flash hider, although with either device mounted the brake would be rendered ineffective at reducing the rifle’s recoil. As per the Benning recommendation, the magazine designed for the T20E2 was compatible with the existing BAR, but the reverse pairing was not possible.

The grenade launcher for the T20E2, and its interface with the rifle’s substantial muzzle brake. Note that the launcher blocks the brake’s ports, rendering it ineffective. Image source: Stevens

So serious was Ordnance about adopting the T20E2, that when, in June of 1945 the first 10 rifles were completed, they were immediately sent to Raritan Arsenal for “preparation of Notes of Materiel”, that is, to create a field manual for the weapon. The resulting document was War Department Technical Bulletin TB 9X-115, dated June 28, 1945, and it is replicated in full in Stevens’s book. Despite this expedited timeline, series production of the T20E2 was not anticipated to begin until January of 1946. However, Operation Downfall, the anticipated invasion of Japan, was set to begin at the end of 1945, and was estimated to last at least until 1947. In mid-1945, the T20E2 was set to be the primary weapon of Operation Downfall, and so it was essential to get the rifle ready for action as soon as possible.

On August 6th, 1945, another secret U.S. weapon was used against Japan. Dropped from the B-29 Superfortress heavy bomber Enola Gay, the uranium-235 gun-type fission bomb dubbed “Little Boy” destroyed most of the Japanese city of Hiroshima. Three days later, another B-29, Bockscar, dropped the plutonium-239 implosion-type fission bomb “Fat Man” on the city of Nagasaki. With this, and the commencement of the Soviet invasion of Japan earlier that day, the Japanese Emperor Hirohito decided to surrender to the Allies, accepting the terms of the Potsdam Declaration. On August 15, 1945, Hirohito gave a radio address announcing the surrender, and on September 2, 1945, the Japanese Empire signed its formal surrender aboard the USS Missouri, finally ending World War II.

Just like that, the Atomic Age had begun, and the adoption of the T20E2 suddenly evaporated. That month, the Ordnance Technical Committee shelved the adoption of the rifle, although it did not end the program. In fact, the T20E2 rifles would continue to serve as testbeds for the weapons that would eventually lead to the M14 throughout the late 1940s and early 1950s.

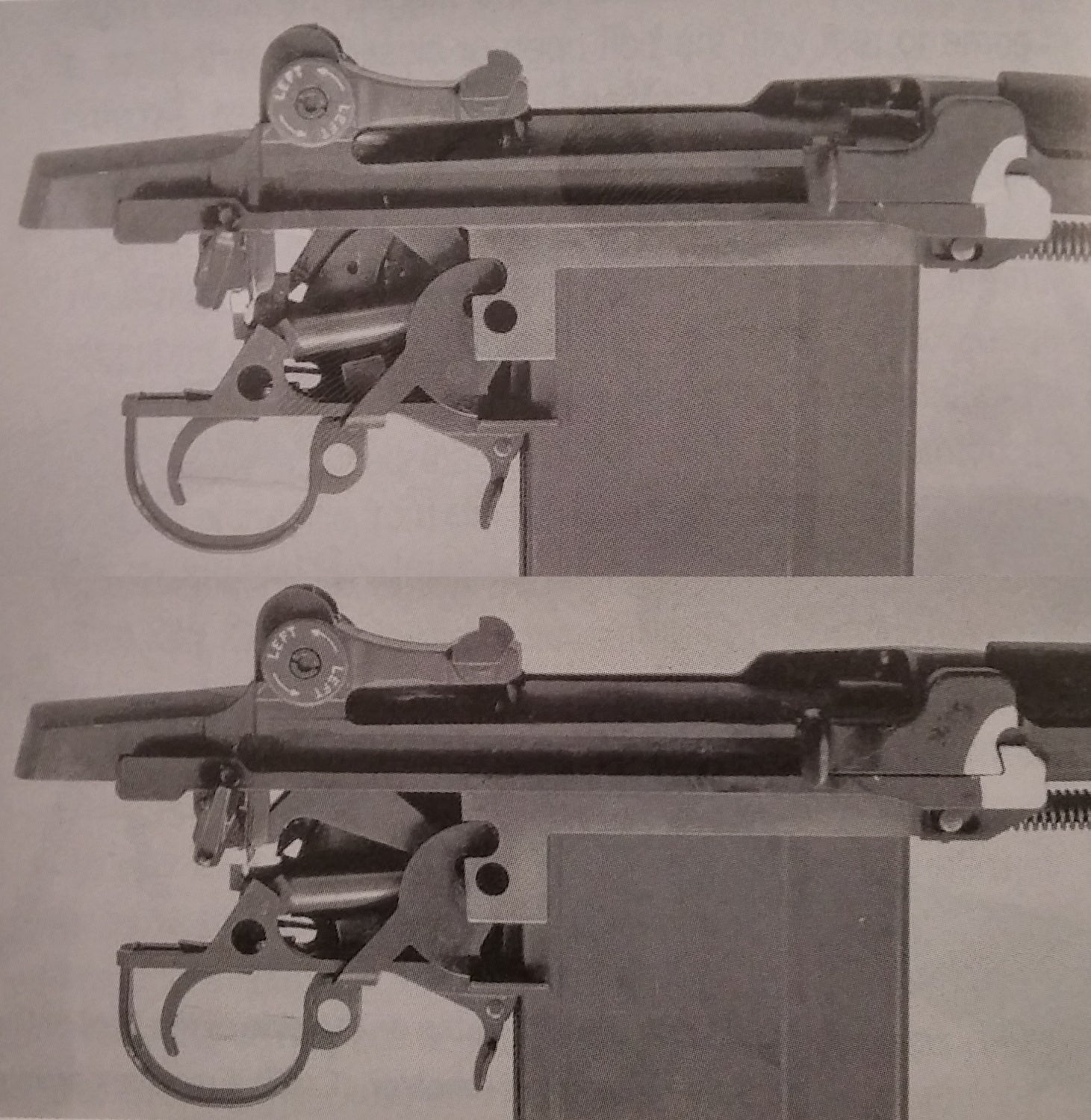

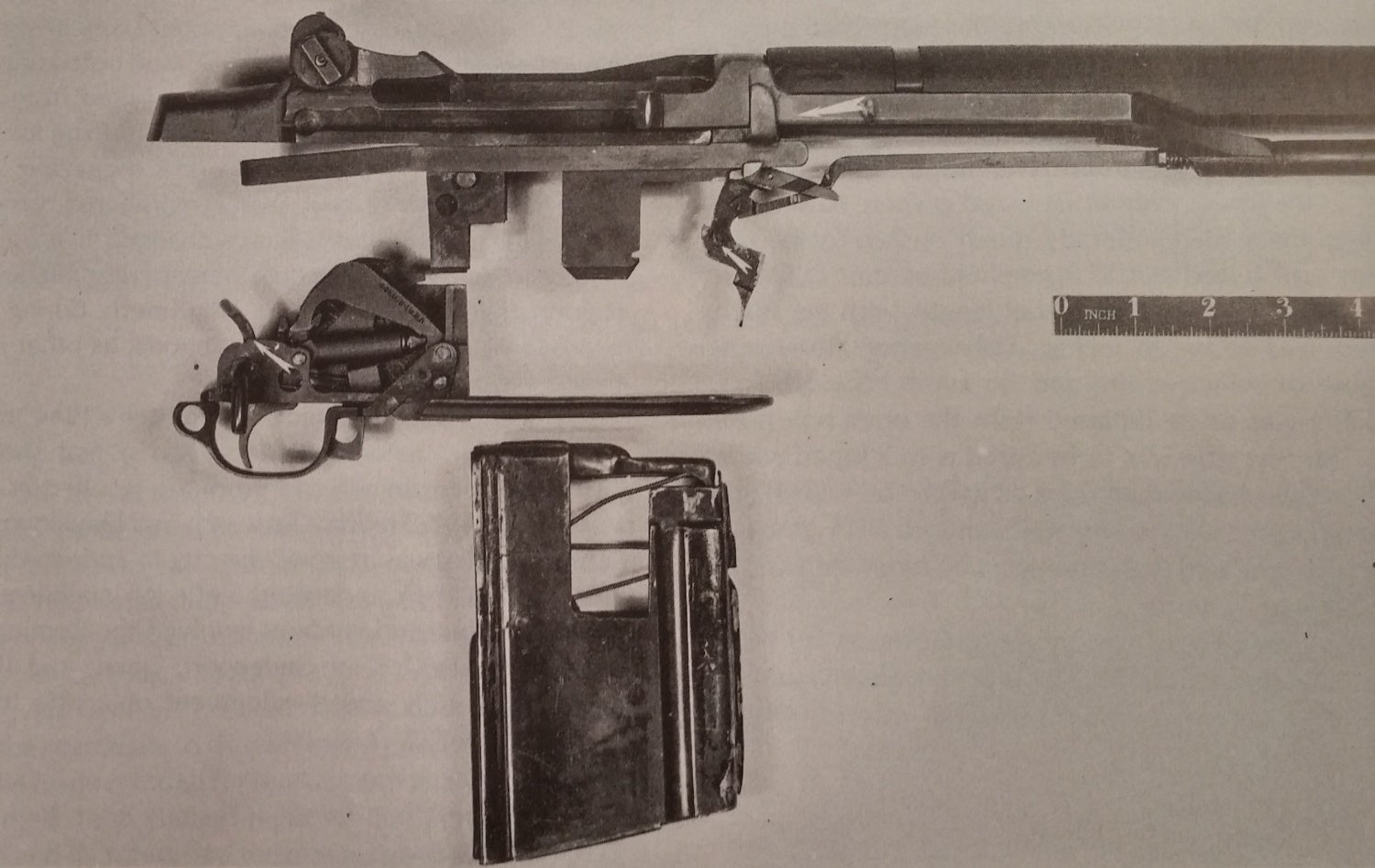

The mechanism of the T20E2, which was carried over to the T44 prototypes (which were themselves based on re-used T20 receivers), and eventually the T44E4 that was standardized as the M14 in 1957. Image source: Canfield

Remington Development: The T22, T23, T24, and T27

In addition to Springfield Armory, Remington Arms Co. was in September of 1944 given the second of two contracts for a new select-fire, folding stock “paratroop” rifle derivative of the M1. Given the requirement for 85% commonality with the existing M1 rifle, the leadership at Remington decided that the most expedient course of action would be to design a rifle that retained as much of the original design as possible, and unlike those at Springfield Armory, Remington’s developments would all retain the standard M1 receiver length. Remington’s project was given the designation “T22”.

As work proceeded in the first few weeks at Remington, two distinct methods of facilitating fully automatic fire became apparent. The first, like the Springfield T20, was to add an extension to the rifle’s sear, which would be tripped as the operating rod reached its frontmost position in the receiver, after the bolt had been locked. The second was championed by Remington engineers Kenneth J. Lowe and Crawford C. Loomis, and utilized a hammer release stud. Switching the selector to fully-automatic caused a specially shaped piece would disengage the hammer from the rifle’s sear, while simultaneously engaging the hammer release surface with a stud on the hammer. Upon the return of the bolt to battery after firing the first shot, the forward surface of the operating rod would contact a connecting bar, forcing the hammer release surface out of alignment with the stud on the hammer, and releasing the hammer, causing fully automatic fire that would continue until the release of the trigger.

To test both of these designs, Remington modified two existing M1 rifles, which became the T23 with the independent hammer release, and the T24 with the independent sear release. The tests showed to Remington the value of the independent hammer release fire control group, and at this point it became obvious to Remington and Ordnance both that the requirements for the project were unrealistic. On a meeting between Col. Studler, Major E. G. Cooper, and Kenneth Lowe on November 1st and 2nd of 1944, the requirements specified in the contract were modified:

- Weight – not to exceed 12 pounds, less magazine.

- Eliminate the folding stock requirement, and use the standard Garand stock maintaining the standard Garand overall length.

- Use the standard Flash Hider but so modified as to function also as a muzzle jump reducer or stabilizer.

- Use B.A.R. 20-round magazine modified to suit.

- Use modified design of Bren Bipod.

Early in the life of the first T22 prototype, tests at Remington revealed that the rifle needed significant revision. The fire control mechanism gave unreliable and erratic performance. Like the engineers at Springfield, Remington engineers too found that a fully automatic M1 had a tendency to overheat. The magazine was initially retained only in the rear, which resulted in magazine tipping, causing misfeeds. Other problems manifested alongside these, and the T22’s design was modified, becoming the T22E1 on January 13, 1945.

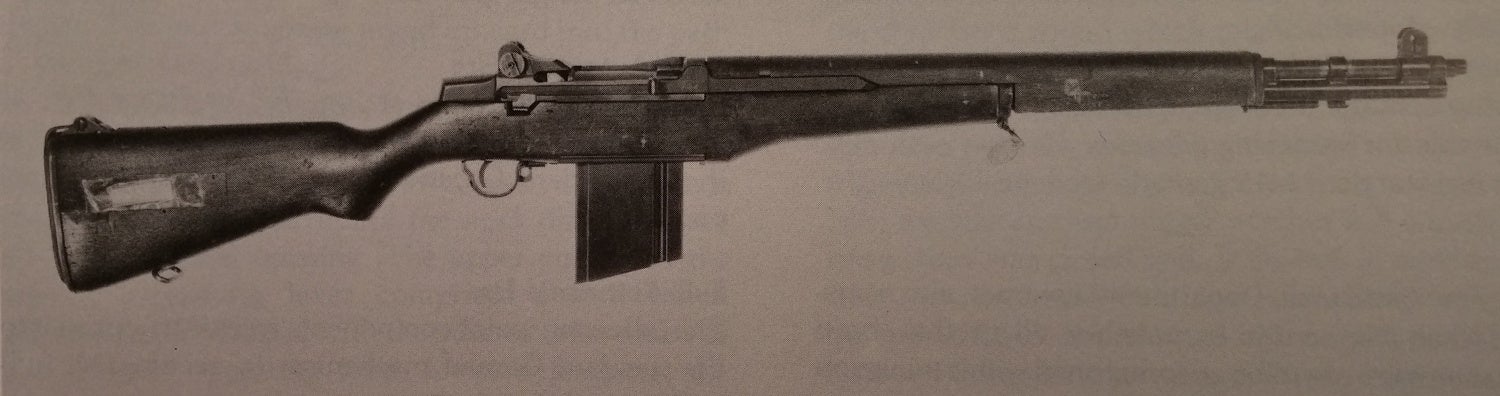

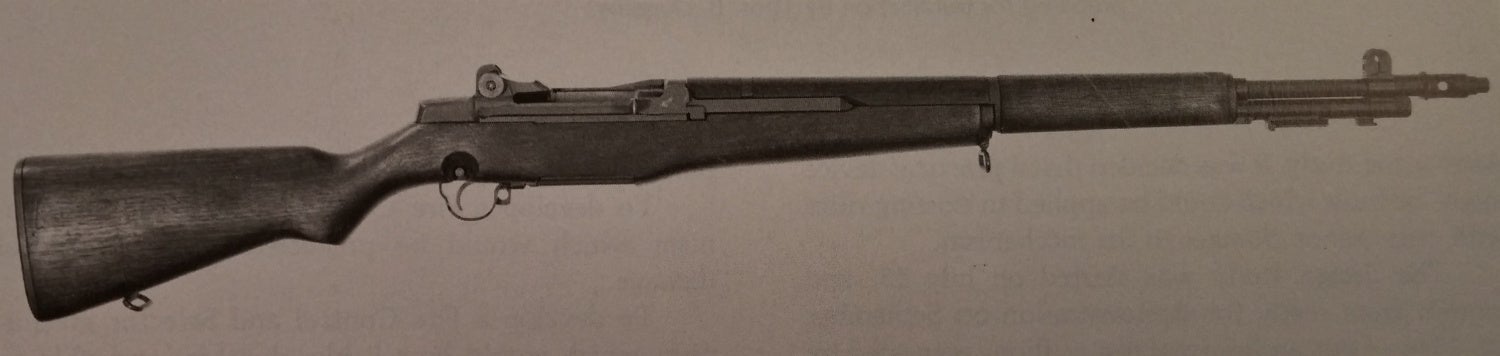

The Remington Arms Co. T22 rifle. This rifle used a hammer release mechanism designed by Remington, unlike the T20. Image source: Stevens

The T22E1 incorporated a host of significant improvements to the Remington design. The magazine issue was solved by supporting it both front and back, a new pattern of magazine with a heavier spring was designed for the weapon that was compatible with the BAR, but that provided a persistent last-round hold open via a catch in the receiver, revised and improved feed ramps were incorporated into the barrel, cooling slots were cut in the handguards, and a bipod was added, based on the British Bren light machine gun bipod. Then, again on January 29th, the design was modified further:

The arm should fire from a closed bolt in both full and semi-automatic operation;

Instead of locking the gun open on the follower, it is requested that the follower operate a separate latch which would retain the bolt in the open position after the last shot;

Improve the effectiveness of the muzzle depressor and ignore its deficiency as a flash hider, if such results.

Finally, by April 2nd, 1945, the T22E1 was ready for testing at Aberdeen Proving Ground. Kenneth Lowe and Crawford Loomis personally delivered the prototype to the testing facility, where it was evaluated by firing six thousand rounds of .30 M2 AP ammunition over four days as part of routine testing. The personnel at Aberdeen were impressed, according to Stevens called the rifle’s performance “excellent”. Further, the rifle’s new magazine pattern functioned perfectly with the Browning Automatic Rifle, satisfying in part the need to share commonality with the existing automatic rifle type.

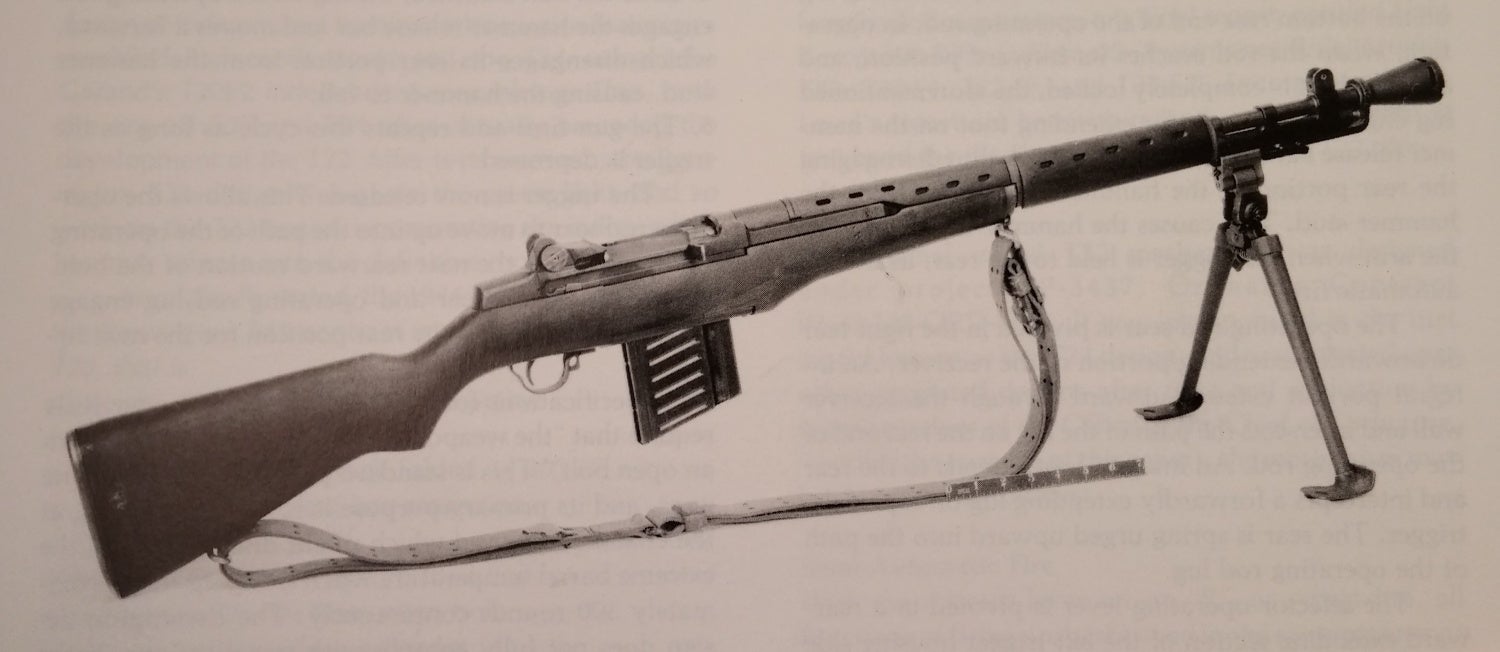

The T22E1 rifle, with improved, ribbed magazine, also compatible with the M1918 BAR. Note the Bren-style bipod, and large cup flash hider modified to act as a muzzle brake. Image source: Stevens

On May 4th, 1945, Remington was represented by Lowe, Loomis, and G. O. Clifford at a meeting in Washington with representatives from Ordnance (including Col. Studler), Springfield Armory, and Aberdeen Proving Ground to discuss the T20E1, T22E1, and the findings thus far as to the proper configuration of the new rifle, whichever was chosen. It appears that at some point in these proceedings, it was decided to dispose of the superior Remington magazine, and revert to the existing M1918 BAR magazine.

Development continued at Remington from this point until after the end of the war. The improved T22E2 prototype was completed by late October, 1945, and submitted for testing before the end of that month. Unsurprisingly the test results showed that the rifle’s cyclic rate was outpacing the BAR magazine’s ability to feed rounds into the action, and this resulted in an inordinate number of closures of the bolt on an empty chamber; interestingly, though, this was the only type of malfunction reported!

Further Aberdeen trials of an improved model of T22E2 were scheduled for July 22nd, 1946, and these reportedly gave excellent results. Subsequently, Springfield Armory was given a contract to fabricate fifty T22E2 rifles for field tests, modified with push-through selectors and Remington-designed muzzle brakes (these were used instead of the T20E2 brakes because of a shortage of those components). Oddly, at one point the new rifles were specified to fire from the open-bolt position in both semi- and fully-automatic fire modes, however it was found that this was a poor match for the somewhat sticky Garand action, as a failure of the bolt to feed a round could result in an unintended discharge.

The T22E2 rifle, with Remington-designed muzzle brake, and revised push-through selector lever. Note the reversion to using M1918 BAR magazines, a change that caused problems with this type. Image source: Stevens

The T22 program concluded with Lowe’s report Light Automatic Rifle Caliber .30 (Paratroop Rifle) Models T22, T22-E1, T22-E2, and T22-E3, submitted on October 15, 1946. However, in February of that year, Col. Studler awarded to Remington a contract to design a select-fire kit that could be installed in existing 8-shot en-bloc clip loading M1 rifles, sending to the company an example of such a rifle designed by John Garand utilizing the sear release mechanism of the T20. Studler’s reasons for requesting this kind of weapon were that existing rifles could be retrofitted to train troops for light automatic rifles, and that fully automatic capability, even with an anemic 8-shot magazine, would still be an improvement in firepower for the squad. Design study for this rifle, named “T27”, began on July 15 of 1946, and the rifle was demonstrated on September 20, 1946, more than a year after the end of the war. The T27 utilized the same mechanism as the T22E2 (with which the components were interchangeable), and was a technical success, requiring only basic field-stripping to give the access needed to modify the rifle’s components for select-fire. Minor improvements made to the Remington mechanism as part of the T27 program were rolled into the T22’s design, as well, resulting in a rifle designated “T22E3”, which was never built.

The T27 rifle, designed by Remington Arms Co. to provide a field kit to retrofit existing M1 rifles for select-fire capability. This improved on the T22E2’s select-fire mechanism, and its design was reincorporated into the T22 program resulting in the T22E3. Note that the rifle does not have a detachable box magazine, retaining the 8-shot en-bloc clip system of the M1. Image source: Stevens

Winchester Development

Legendary Winchester CEO Edwin Pugsley was aware of the development that was happening at Springfield and Remington (both still in their infancy), and felt that if the company did not produce its own select-fire M1 derivative, it would be unable to secure future rifle contracts. Further, Pugsley determined that if Winchester could solve the problem of making a successful select-fire infantry rifle ahead of the other two initiatives, then it could win the contract and have a substantial lead over its competitor, Remington. Pugsley put then-Winchester engineer Harry H. Sefried II in charge of the project. In a memo dated June 22nd, 1944, the first example Sefried’s M1 variant utilizing a 20-round box magazine was documented having fired 135 rounds, with two failures to feed. Sefried’s design utilized a modified, cut-down M1918 BAR magazine, a front-mounted magazine latch operating from a modified set of M1 Garand lockwork with the follower and follower arm for the en-bloc clip system removed, and a sear trip lever actuated by a connecting arm activated by the return of the operating rod to battery.

The Winchester select-fire Garand prototype. This rifle is often misidentified as John Garand’s original select-fire prototype, but it was in fact designed by Harry H. Sefried II. Image source: Stevens

By July, Pugsley had informed the Chief of Ordnance’s Small Arms Division, Colonel Rene R. Studler, that Winchester was pursuing independent development of a select-fire M1-derived rifle. However, Studler’s attitude towards Winchester at this point seemed cold and uninterested. In the transcript of a telephone conversation between Studler and Pugsley in August of 1944, Pugsley asks Studler why Ordnance won’t test their rifle design, and the Colonel responds that the design isn’t finished enough for tests at Fort Benning – saying nothing of Ordnance testing the gun themselves. Studler then told Pugsley that more features, such as a bipod and flash hider, should be added to the design, while not expressing any interest in Winchester’s mechanism itself. Further reinforcing the idea that Studler was dismissing Winchester, he changes topic to the M2 Carbine (which was designed without Winchester’s involvement, or even knowledge), and refuses to send them a sample for testing, but offers to demonstrate it at Springfield Armory instead. The signals received by Pugsley must have communicated to him that Ordnance was uninterested in Winchester’s project, preferring to pursue its own T20 and Remington’s contract.

Harry Sefried’s select-fire M1 design, field-stripped. Note the sear extension and the forward-mounted magazine release, both highlighted by arrows. Image source: Stevens

Still, Pugsley was dedicated to perfecting the select-fire Garand ahead of Springfield Armory and Remington, and on November 21st, Pugsley demonstrated the select-fire Garand, Winchester Automatic Rifle, and M2 Carbine (which Winchester was selected to produce) prototypes at Aberdeen Proving Ground. This demonstration revealed that when firing .30 cal M2 Armor-Piercing ammunition, the soft fronts of the magazine could be dented by the severe recoil impulse of the rifle, combined with the hard bullet tips of the AP cartridges. The magazines used in this test were modified M1918 BAR magazines, and were not designed to resist the much more extreme recoil impulse and rate of fire (955 rounds/min versus 350-450 for the M1918) of the modified Winchester M1. Winchester’s earlier testing had uncovered this problem, but they did not know that the Army planned to use M2 AP exclusively in theater until that point. Prior to learning of this, Winchester engineers had suggested that treating the M1918 magazines as disposable could circumvent the problem. However, their testing thus far had been with lead-cored M2 Ball ammunition, where hardened-steel-cored M2 AP would dent a brand new magazine sufficiently to stop the cartridge stack from rising with only a few shots.

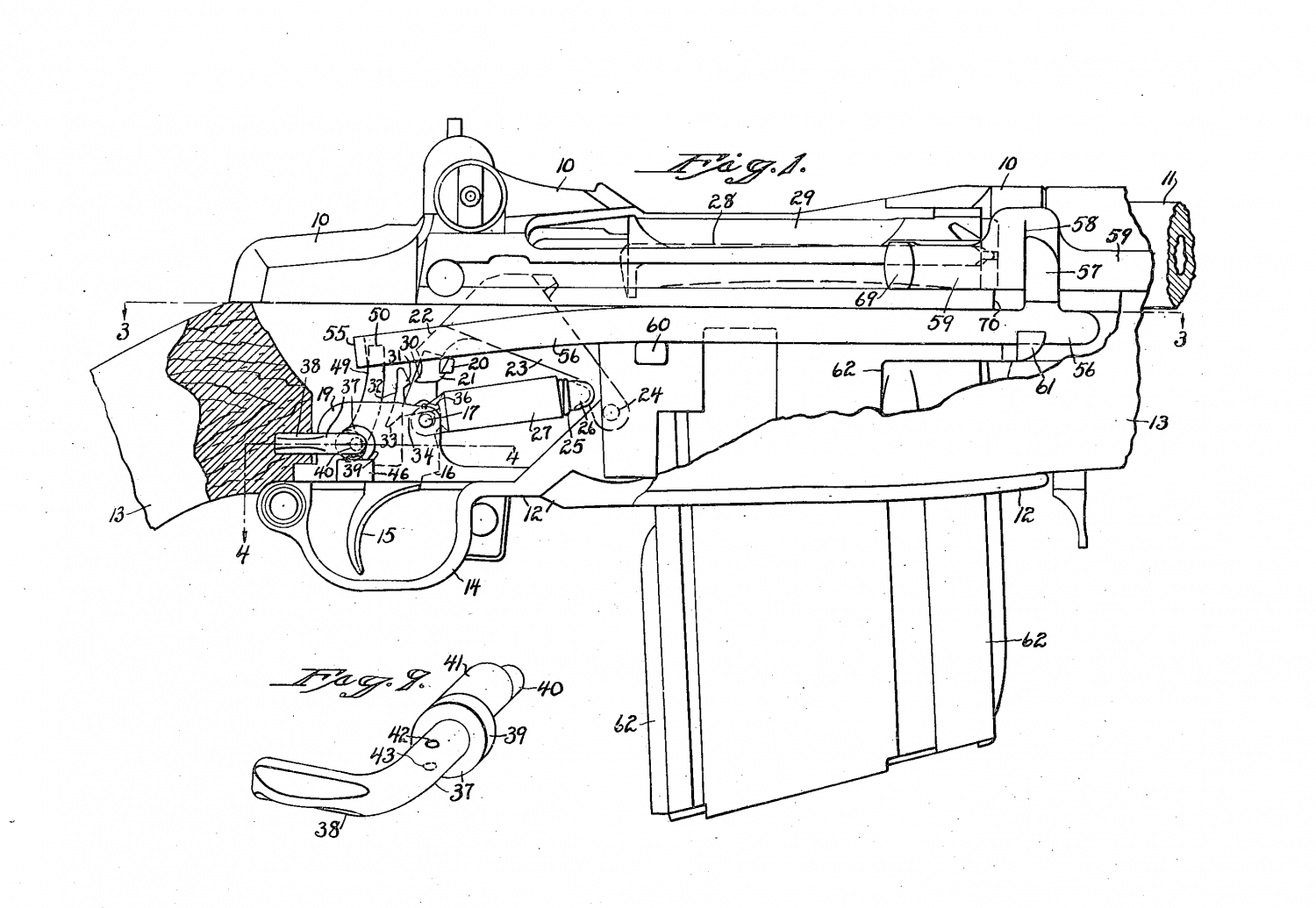

An image from Sefried’s patents on the Winchester select-fire Garand. Note that the rifle described here is identical to the one pictured above. Image source: google.com/patents

As an amusing aside, the lead project engineer Harry Sefried retold a story about Winchester’s select-fire Garand to Charles E. Petty, who authored an article for the 1983 March/April issue of American Handgunner:

One of his first projects at Winchester was to develop a modified M-1 capable of full-automatic fire. Sefried, Roehmer, Pugsley and Williams took the model to Aberdeen Proving Ground to demonstrate it to John Garand and a host of army brass. In honor of his position, Garand was given the first opportunity to fire the gun. Before Sefried could explain the light trigger pull and 1,000-round-per-minute cyclic rate, Garand raised the rifle to his shoulder, touched the trigger and. .. you guessed it! While the assembled dignitaries scrambled for cover, Sefried grabbed Garand and held on. He says it was the high point of his career-“to have John Garand by the ass.”

After the demonstration, Col. Studler continued to play coy with Winchester. In mid-December of 1944, Pugsley inquired of the Colonel whether Ordnance would still be interested in their select-fire M1, on which work was still well underway. Studler, who was surely unimpressed by the Winchester gun with its magazine issues, low total round count to that point, extremely high rate of fire, and lack of features, responded noncommittally on December 20, 1944:

Concerning your letter of 12 December 1944 and in particular the matter of the Browning Automatic Rifle magazine your conclusions as to the effect of this item on functioning agree with ours. It seems to be quite evident that an improvement in the magazine is required for correct functioning of this weapon.

In answer to your last paragraph, we will of course be glad to arrange for tests of any further developments which you may accomplish.

Interestingly, readers will note that at this point only the initial Springfield T20 prototype had been produced, and was itself having problems. Despite Studler’s non-answer, Winchester continued to work on the firearm through 1945, as evidenced by a June report sent by Winchester to Colonel Studler. Most likely, given Pugsley’s tenacity for a contract, Winchester development of this weapon ended with the end of World War II, however the company will re-enter our story later on in the series.

To Conclude

Thus, we have seen that at the end of World War II, or shortly thereafter, Ordnance had in its grasp no less than four rifles (T20E2, T22E3, and Winchester’s select-fire M1 and the Williams-designed G30R discussed in Part II) that offered what they were looking for in a next-generation infantry weapon. These rifles were chambered for standard .30 caliber ammunition, and any one of them could have been tested, adopted, and produced before the end of the 1940s. However, as we’ll see Ordnance would choose “perfect” over “good enough”, as a future installment will cover the fateful decision to abandon the .30 M2 caliber in favor of an entirely new round. This, combined with the collapse of another program, and the “life support” level of funding that the Garand improvement program would receive post-war, would cause a 12 year delay in fielding a weapon of this kind.

Addendum

It should be noted that one enemy weapon possibly had a tremendous amount of influence on the Army’s search for a select-fire infantry rifle during this period. The German Fallschirmjägergewehr, or FG-42, was a select-fire weapon in the German standard 7.9x57mm cartridge, and had proven to be surprisingly lightweight and controllable, even on fully automatic. The weapon, which was designed for Luftwaffe paratroops building upon experience in the Battle of Crete, operated from a closed bolt in semi-automatic mode and an open bolt in fully automatic mode. According to several secondary sources, the FG-42 was received by US testers with great enthusiasm, and the timing of at least one of those tests was fairly conspicuous. Given the specific requirements of the U.S. program, and even the name given in the initial solicitation, which was for a paratroop rifle, it seems highly probable to me that the FG-42 gave the Ordnance Department all the justification it needed to set such ambitious requirements. After all, if the Germans could produce such a weapon, why couldn’t the United States? And if such a weapon could be produced, why shouldn’t all U.S. troops be armed with it? The above remains entirely my own speculation, but it’s possible – probable, even – that the FG-42 paratroop rifle represents the true first light rifle, and that it was this German weapon that so thoroughly convinced the Army that a select-fire, full-caliber lightweight automatic rifle could be made a practical reality.

An early-model FG-42 paratroop rifle. There is not enough direct evidence to conclusively determine that it was this weapon that convinced Ordnance to pursue the path of a select-fire, full-caliber infantry rifle, but in this author’s opinion that is highly probable given the circumstantial evidence. Note the date of the photo, 9 August 1944. Image source ww3.rediscov.com

Your Privacy Choices

Your Privacy Choices