The Spencer Carbine was one of the first successful repeating rifles ever fielded by the US Army, seeing use in the Civil War. Despite being a very advanced design for the period offering firepower well above what muzzleloading rifled-muskets of the period were capable of, the Spencer has been denigrated in retrospect due to its cartridge, which has been perceived to be underpowered. Shawn of LooseRounds takes a look at some of the anecdotes surrounding the Spencer in a recent article:

The first model fired a .52 caliber cartridge called the .56-52. this was the model that saw service in the Civil war. According to cartridges of the world , this round was only a fraction more powerful than modern smokeless factory loads in the .44-40. For sporting use the round was considered short range and not effective on anything larger than deer even when fired from the rifle length barrel. While most users had nothing but praise for its robustness and reliability to stand up to repeated firing and fouling, its main short coming would come to light.

The death of Roman Nose is well known and worth repeating because it an example of the inadequate performance of the cartridge from the Spencer. He kept a low profile throughout most of the fighting. Believing fully in the power of the medicine in his war bonnet, a single horned affair made for him by a medicine man named White Bull. The power of the bonnet could be rendered ineffective if before the battle he ate food served to him with a metal implement. If he did so, a cleansing ceremony was needed to restore the magic of his bonnet. A squaw served him some pan bread she removed from the pan with an iron fork. There was not enough time to perform the cleansing and being pressured, he joined the fight. Roman Nose went into the battle convinced he would die.-AR

He led a mounted charge of a small band against the scouts and made the same error as did Weasel Bear. Riding over the small group of scout secured under the over hang in the near dry river bank. A Spencer ball hit Roman Nose in the back just above his hips. He did not fall from this mortal wound but returned to his own lines and back to his own people to finally die before sundown.

Having much faith in the power of their medicine, one of the boys who was at the Beecher Island fight changed his name to Bullet Proof as a result of his battle experience that day. Bullet Proof had been shot in the breast and it appeared ( appeared that is) the bullet passed through him exiting his back. According to this fanciful lad, he was able to stop the bleeding and heal the wound by only placing his hand on the ground and rubbing his wounds. If this is his medicine the wounds were very slight indeed. “Had he been hit like Gunga Din where the bullet come and drilled the beggar clean, a stronger remedy surely would have been required” – Tate Most likely the young warrior was hit by a bullet at some distance as he rode toward the island and possible once again as he rode away. Unfortunately for his pals he was overly impressed with his own invincibility and practiced a dubious medicine that got two of his friends killed. Supposedly immune to bullets due to Bullet Proofs methods, two friends were later killed while charging the troopers in the 10th Cav. later.-Tate

It doesn’t look good for the ol’ .56 Spencer, but Shawn thinks (as do I) that there is probably more to the story:

No doubt, another contributing problem is the same thing seen during the Korean War. In that case, it is the M1 carbine and its .30 carbine cartridge that takes the blame. Veterans from the war claiming the M1 carbine round so small in comparison to the full size service cartridge just had to be the problem. When shot at charging communist troops in their thick quilted coats failed to move to the next life, the men, as they always do, blamed the puny round and not marginal hits or misses. Had to be the round not doing it’s job. Blaming the gun and not the shooter is a timeless tradition. With the Cavalry troopers surrounded and in a desperate fight, taking snap shots on moving targets moving through high grass and on horses, while under withering fire,it is easy to come to the conclusion all but the most close range shots were certain. The confirmed dead is testament to that.

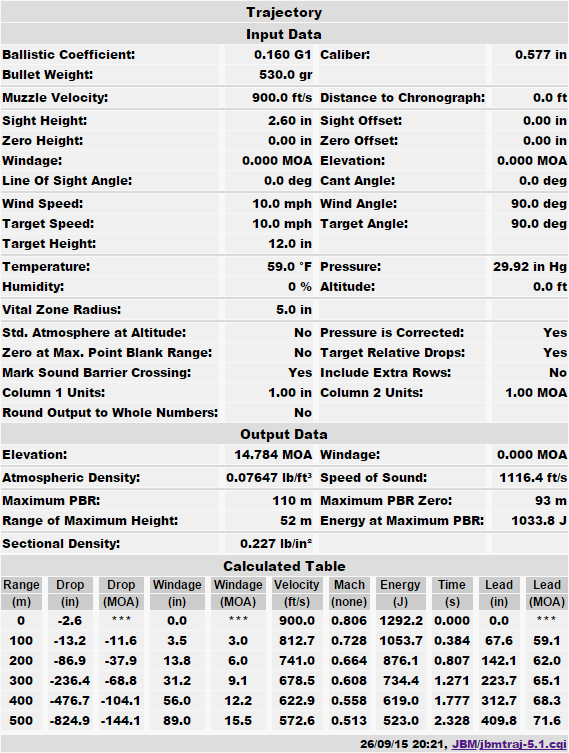

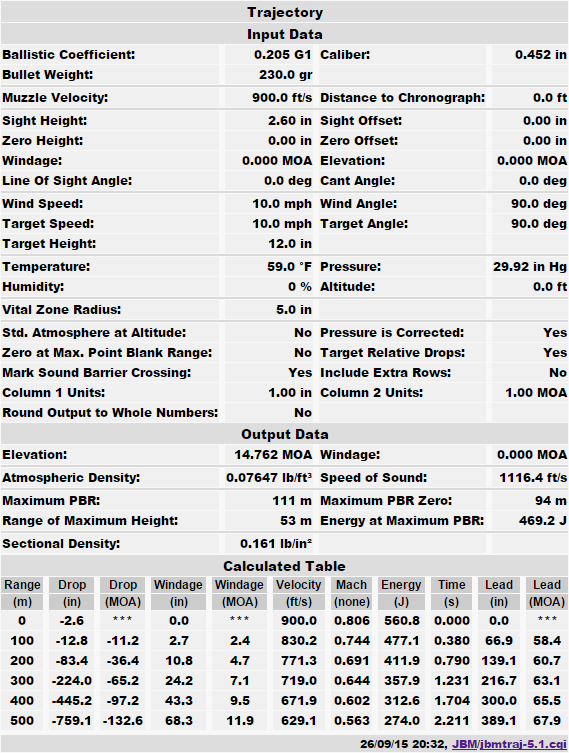

Ballistically, the .56 Spencer (of which there are several variations, but all of which are ballistically equivalent) is not particularly anemic for the period. The carbine fired a bullet of about 350 grains at a muzzle velocity of approximately 1,200 ft/s, which gives a muzzle energy of approximately 1,520 Joules. For comparison, a Pattern 1853 Enfield rifled-musket with 2.5 drams of blackpowder, firing a 530 grain Minie ball gives muzzle velocities in the 900 ft/s range, for a muzzle energy of ~1,290 J. So, in fact, at short ranges the Spencer gives more energy than a standard musket, implying better terminal effectiveness. However, the Spencer fires a much lighter bullet with a lower ballistic coefficient, which both means its velocity will drop off much more quickly, and that it will have less penetrating power. How big of a difference does this make? Let’s compare, the top graph being the .56-56 Spencer, and the bottom being a Minie ball fired from a Pattern 1853 rifled-musket:

So, in terms of energy, the rifled-musket clearly pulls ahead almost immediately, giving over 100J more energy than the Spencer by a scant 100 meters, a gap that only widens as ranges increase. It’s therefore not unreasonable to suggest that a typical rifled-musket of the period was more effective than the Spencer, but what about claims that the round didn’t penetrate deeply enough? That seems unlikely; the .56-56 Spencer similar velocities out to 300 meters to the modern .45 ACP pistol round, which fires a lighter, smaller caliber bullet of almost identical sectional density.

One could perhaps suppose the .56 Spencer was prone to flattening or tumbling, which could reduce its penetration, but surely that wouldn’t reduce penetration so significantly vs. the .45 ACP that it would leave its target barely scathed, and such effects should, in theory, actually improve it’s immediate terminal effectiveness!

In my opinion, Shawn has the right of it in attributing at least some of the Spencer’s terminal effectiveness woes to “.30 Carbine syndrome”, where in the midst of frenetic combat misses are conflated with ineffective hits.

Your Privacy Choices

Your Privacy Choices