[ The Editor: The Firearm Blog readers are an innovative group. We regularly get email from readers asking us for give advice on how to proceed with patenting thier gun-related inventions. I am very pleased to present the first part in a series of posts that demystify the subject of patents. The posts are written by “Your Patent Friend”, a practicing patent attorney. Please note the disclaimer below1. ].

What Is a Patent?

I have corresponded with Steve, and I occasionally post in the comments under the name “Your Patent Friend.” He asked me to write a guest post on the subjects of patents and firearms. While I agreed, it is a subject that cannot really be fairly treated in a single post or two without either doing more harm than good by being too brief or boring the bejesus out of everyone with an insanely long post. I will begin with an overview of what a patent is. I apologize if the information is dry at times. In the installments, the material will be approached from the perspective of an inventor having an invention, and who is considering whether it is worthwhile to seek patent protection for the invention.

In other follow-up posts, I will treat topics such as what can be patented, parts of a patent, procedures, costs, and pitfalls, general advice, and patent resources. If there is a particular interest or question you would like addressed, note it in the comments, and I will try to answer it there or in a subsequent post.

I am a practicing attorney with about six years of experience in patent law, and I am a firearm enthusiast, reloader, hunter, and veteran. Please note the disclaimer[^1] . Also note that there is a wealth of information at the USPTO2 and elsewhere on the net, so there will be references to that material frequently3 . As a result, I will only treat the information here generally and only with respect to the US patent system.

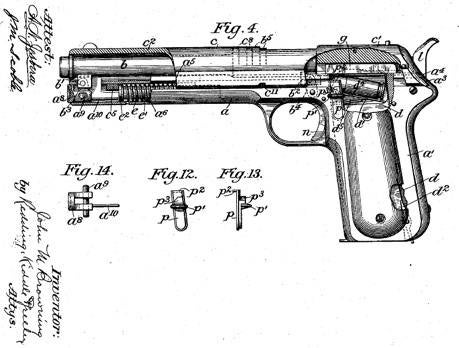

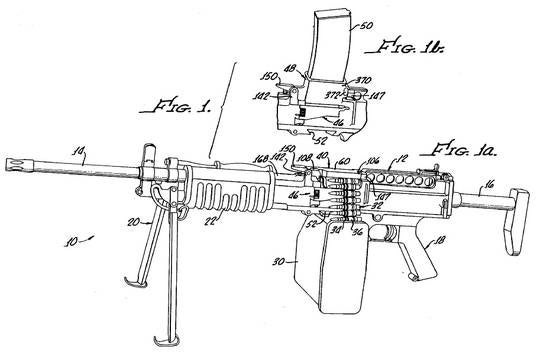

What is a patent? Strictly speaking for our interests, we are talking about a “utility patent” (as opposed to a plant or design patent4 ). A patent is a property right to an inventor to exclude others from making, using, offering for sale, or selling the invention throughout the U.S. or importing the invention into the U.S. for a limited time (20 years from filing the application for patent) in exchange for public disclosure (the patent specification) of the invention.

When you are granted a patent on your invention, depending on the quality of the patent, it can be a valuable right that can be sold, licensed, or bartered, or otherwise negotiated for monetary or other valuable consideration. It does not automatically confer any value other than allowing you access to the courts to enforce your property rights over an infringer. In turn, this potential of litigation and infringement damages is what lead parties to negotiate agreements regarding patent property rights.

What Can Be Patented?

In the last section, we discussed patents, generally. Now we turn to what can be patented. Again, please note the disclaimer[^1].

What can be patented5 ? Any “new and useful process, machine, manufacture, or composition of matter, or any new and useful improvement thereof6” can be patented subject to further conditions and requirements of U.S. patent law. “Processes” are methods of doing things (e.g., process of loading a cartridge from a magazine), whereas a “manufacture” concerns articles that are made (e.g., a rifle barrel). “Composition of matter” refers to chemical compositions (e.g., composition of a smokeless powder or priming compound), and “machine” is self-explanatory (e.g., trigger mechanism). What do these classes exclude? Generally speaking, mere ideas, suggestions, and/or laws of nature, without a practical application that fits into one of the categories above, are not patentable.7

A related question is: What are further conditions and requirements of U.S. patent law? There are many, but the big ones are that the invention be “useful,” “new” (or novel) and not obvious8, and that the patent applicant be the inventor9. The requirement that the patent be “useful” is a relatively low bar and any stated utility should suffice (e.g., the invention makes A move toward B more efficiently, with less noise, more cheaply, etc.).

Generally speaking, an invention is new or novel10 if it meets the technical requirements of the statutory provisions in 35 U.S.C. § 102 (a) and (b), which provides actions and people, places and timelines for the actions that could result in a decision by the USPTO that your invention is not new or novel. The gist is that the question is addressed by the USPTO after the inventor has filed his or her application, based on documentary evidence (e.g., patents, patent applications, research papers, sales literature, the internet, etc.) available before the inventor files his application. The USPTO looks back into history to determine if the requirements of 35 U.S.C. § 102 (a) and (b) are met. If the USPTO is not satisfied, your invention is said to be anticipated by the prior art, which is the same as saying it is not new or novel11.

A non-obvious12 invention is one in which, “though the invention is not identically disclosed or described as set forth in” 35 U.S.C. § 102 (a) and (b), “the differences between the subject matter sought to be patented and the prior art are such that the subject matter as a whole would have been obvious at the time the invention was made . . . .” The gist here is that, even though no single reference anticipates your invention, in light of what was out there at the time you filed your application, the USPTO considers that your invention would be obvious (and unpatentable), considering the perspective of “a person having ordinary skill in the art to which said subject matter pertains13.” Note that when considering the question of obviousness, multiple references can be combined by the USPTO to assert that your invention is obvious.

We treated some of the considerations here of what can be patented and some conditions and requirements of U.S. patent law that govern whether a patent is granted. Without getting ahead of myself, the considerations of 35 U.S.C. §§ 101, 102, and 103 generate a large portion of the work of a patent attorney after the application is initially drafted and filed. Suffice it to say at this point that, even though your invention may have been judged to be anticipated or obvious, your hopes should not be dashed. There is opportunity to argue these conclusions. Without turning this into an advertisement, this is one of the places where, other than seeking services for application drafting, it pays to seek competent and quality service providers.

In the next post, we discuss parts of the patent as a prelude to discussing the procedures for obtaining a patent and the costs associated.

-

Please note that this discussion does not constitute legal advice and does not establish an attorney-client relationship until such time as an attorney-client relationship is formed by execution of a formal written fee agreement that delineates the scope of representation and fee agreement. It is intended to offer general business information regarding typical processes and costs associated with attempting to secure patent protection in the United States, except where noted, as it applies generally, without taking any particular individual’s facts and circumstances into account and without regard for any specific legal inquiry. Further note that any confidential information should be withheld from the discussion until such time as an attorney-client relationship is formed by execution of a formal written fee agreement. If you need legal advice, please contact an attorney directly and verify that the attorney will be entering into the attorney-client relationship and will be rendering the legal advice sought. ↩

-

The United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) is a good resource for learning about patents. Here they describe patents. The USPTO provides further general information in a FAQ-like format here. The prospective patent applicant would do well to familiarize himself/herself with the information at this link. ↩

-

It would be remiss to not mention the Manual of Patent Examining Procedure (MPEP), the manual by which the USPTO operates, and which contains all referenced statutes and rules. It is premature at this point to get into it, other than to mention its availability and content. ↩

-

Thus, the idea that you could increase the velocity of a projectile by reducing wind resistance is not patentable, but specific dimensions, profiles, or surface treatments of a projectile that can accomplish such an objective could be. ↩

-

“Novelty And Non-Obviousness, Conditions For Obtaining A Patent” ↩

-

35 U.S.C. 102 Conditions for patentability; novelty and loss of right to patent. ↩

-

35 U.S.C. 102 (c)-(g) provide further conditions for patentability such as the requirements that the inventor not have abandoned the invention (an inquiry based on lapse of time from invention date to filing date) and that the applicant be the actual inventor, among other requirements. ↩

-

35 U.S.C. 103 Conditions for patentability; non-obvious subject matter. ↩

-

A person skilled as an electrical engineer would not be appropriate level of skill when judging the obviousness of a mechanical invention. The reverse is also true. ↩

Your Privacy Choices

Your Privacy Choices